On the Early Days of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Rise to Power

The Soviet Union General Secretary’s Anti-Alcohol Campaign, Initial Allies, and Rock-Star Beginnings

General Secretary Konstantin Chernenko dies at Moscow’s Central Clinical Hospital on March 10, 1985. The first person to be informed of his death is academician Yevgeny Chazov, the chief physician of the Central Committee. Chazov knows that who he informs first will influence everything to come. In the Ottoman Empire, when a sultan died, each of his sons would race to the palace to claim the throne first—while the Politburo is not quite as dramatic, it’s close. Chazov first calls Mikhail Gorbachev, then KGB chairman Viktor Chebrikov.

It’s the evening of March 10. Gorbachev quickly understands that he must act immediately. He schedules a Politburo meeting for 10:00 that night. Almost instantly. Gorbachev also asks Foreign Minister Gromyko to meet with him thirty minutes before the meeting. “We need to join forces,” Gorbachev says. Gromyko agrees.

It’s clear that only those in Moscow will be able to attend. As it happens, many key players are away: Ukrainian leader Volodymyr Shcherbytsky is in San Francisco, having just flown in from Washington; Central Committee Secretary Grigory Romanov is on vacation at the Lithuanian resort of Palanga. Gorbachev’s rivals scramble to return to Moscow, but none succeed.

Essentially, Gorbachev is asking his main rival: “Are you ready to fight me?”

Romanov can’t fly out of the Klaipeda airport and must drive to Vilnius to catch a flight to Moscow (later, actor Gennady Khazanov would recall hearing that Klaipeda’s Soviet official had been instructed to leave the runway uncleared of snow to delay Romanov’s flight as much as possible). Shcherbytsky, meanwhile, is routed through New York instead of directly to Moscow, so he, too, misses the crucial meeting.

Before the Politburo meeting begins, Gorbachev approaches the head of the Moscow Communist Party, Viktor Grishin, and, with an edge in his voice, asks if he wants to chair the funeral commission. It’s a direct challenge—traditionally, the head of the funeral commission becomes the next General Secretary. Essentially, Gorbachev is asking his main rival: “Are you ready to fight me?” With Gorbachev in control of the meeting, Grishin is caught off guard. He reflexively declines, withdrawing himself from the running before the meeting even starts. Other Politburo members witness this exchange.

The meeting adjourns after that—officially, the Central Committee Plenum must select the General Secretary. Gorbachev suggests holding it the next day, with the Politburo meeting beforehand to finalize the recommendation. The members leave, but Gorbachev remains at work late into the night.

Alongside his longtime friend jurist Anatoly Lukyanov, he drafts the speech he’ll deliver at the Plenum. Other members of his team—Yegor Ligachev, Nikolai Ryzhkov, and Alexander Yakovlev—stay too. Ligachev spends the night contacting regional party leaders, who are also Central Committee members and will vote at the Plenum. Having begun replacing old Brezhnev-era officials with younger ones during Andropov’s tenure, Gorbachev and Ligachev have many supporters among the regional leaders, who feel indebted to Gorbachev. Ryzhkov, who oversees the government from the Central Committee, focuses on securing support from younger ministers.

In the morning, at the Politburo meeting, as agreed, Gromyko speaks first and proposes Gorbachev. The others chime in, praising the candidate. The vote is unanimous.

Several TV operators are recording the entire interaction. The resulting footage is stunning: the young, energetic General Secretary looks like a rock star surrounded by adoring fans.

What to expect from the new, young General Secretary, no one yet knows. Chess player Garry Kasparov recalls that around the time of Gorbachev’s election, he visits a friend and a filmmaker, Mikhail Kozakov. All of the guests talk of one thing: Will the new General Secretary bring change, or will everything stay the same? Young Kasparov predicts that change is inevitable. But the older guests disagree. Historian Natan Eidelman, then fifty-four, says, “I’ve lived a long life. Mark my words: they’ll make some noise and then settle down.”

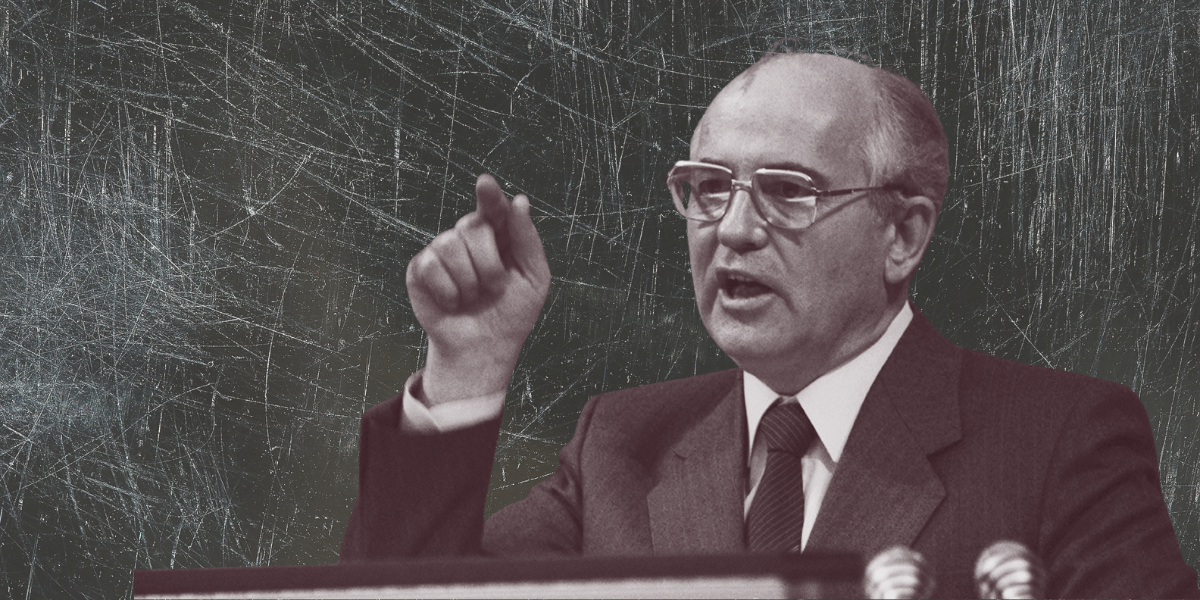

In May 1985, a crowd gathers near the Moscow railway station in Leningrad. The reason is startling: Mikhail Gorbachev, the new General Secretary, has spontaneously decided to walk among the people, spending half an hour talking with Leningrad residents. “Stay close to the people, and we’ll never let you down!” a woman shouts at him. “How much closer can I get?” Gorbachev responds with a laugh, prompting laughter from the crowd.

Several TV operators are recording the entire interaction. The resulting footage is stunning: the young, energetic General Secretary looks like a rock star surrounded by adoring fans. After years of stiff, elderly leaders, here is a leader who talks to people like a real person. The footage is shown to his wife, Raisa, who is moved to tears. “Everyone needs to see this,” she insists, and that very evening, the full version airs on the main news program, Vremya.

Soviet TV viewers’ infatuation with Gorbachev, however, will be short-lived. For the first few months, his ability to speak “without a script” will seem like a miracle. But before long, the frail Brezhnev and Chernenko will be forgotten—and the new General Secretary will come to be seen as someone who simply talks too much: at length, with passion, but ultimately without clarity. Most viewers will dismiss his speeches as mere empty demagoguery.

Yet there is another problem with Gorbachev’s speech—his strong southern accent. This is how people speak in Eastern Ukraine and southern Russia, but typically, it is associated with the uneducated; those who have received a higher education usually rid themselves of this dialect. In this regard, the Soviet Union is far from a tolerant country—standard Russian, as spoken in Leningrad and Moscow, is considered the norm, and any deviation from it is viewed as deeply embarrassing. That’s why many are astonished that Gorbachev never even tried to shed his rural pronunciation.

Within his first months in power, a key word enters Gorbachev’s vocabulary: “perestroika”—“restructuring.”

Moreover, he frequently places the wrong stress on even the simplest words (and even more so on complex ones), sometimes even inventing his own, entirely nonexistent terms. This hardly creates the image of an intellectual— rather, he comes across as an overconfident provincial who enjoys speaking but does not always fully grasp what he is saying.

Within his first months in power, a key word enters Gorbachev’s vocabulary: “perestroika”—“restructuring.” Everyone likes the sound of it, though no one quite knows what it means. Yet this word will soon become the slogan of his entire tenure and the symbol of all the changes to come in the USSR.

After assuming leadership, Gorbachev begins slowly replacing the old Brezhnev-era Politburo members, although he lacks many suitable candidates. In April 1985, he appoints the key allies who helped him come to power—all loyal Andropov men: Central Committee secretaries Yegor Ligachev and Nikolai Ryzhkov, and KGB chairman Viktor Chebrikov.

Over the following months, he dismisses senior officials carefully and individually: in June, he retires Grigory Romanov, his recent rival; in September, he replaces Premier Nikolai Tikhonov with Nikolai Ryzhkov; and in December, he parts ways with Moscow boss Viktor Grishin. For his successor, Gorbachev lacks a personal ally and accepts Ligachev’s recommendation of an energetic official from Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg): Boris Yeltsin.

Ligachev, who oversaw the neighboring Tomsk region, believes Yeltsin is a highly effective manager—the kind of person needed for Gorbachev’s “acceleration” campaign. However, Ryzhkov, also from Sverdlovsk and previously director of Uralmash, strongly disagrees. “You’ll regret this decision,” he warns, but Ligachev insists.

At that time, Yeltsin has led the Sverdlovsk region for eight years. In his memoir, he describes his sadness about leaving: he’s spent his whole life in Sverdlovsk; he’s fifty-four, with children and a granddaughter. He has no idea how radically his life will change in Moscow. He later writes that, like most Soviet people, he regards Muscovites with suspicion, seeing them as snobs and Moscow as a Potemkin village—a beautiful showcase for foreigners.

Becoming First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee, he fully grasps Gorbachev’s expectations: “Fight the mafia, overhaul the personnel, and dismantle Grishin’s team,” he will write in his memoir.

However, Gorbachev’s most challenging Politburo member is Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko. On one hand, Gorbachev feels indebted, as Gromyko supported him in his bid for power. On the other hand, Gorbachev disapproves of Gromyko’s old-school Stalinist approach, characterized by an unwavering “Mr. Nyet” stance on negotiations. While Gromyko believes in talking only from a position of strength, Gorbachev wants to pursue diplomacy. Gromyko, in turn, grows increasingly frustrated, confiding to his son that the new General Secretary starts too many initiatives without finishing any.

In June, Gorbachev fulfills a promise: the Supreme Soviet appoints Gromyko as chairman, making him the ceremonial head of state. And he appoints Georgian party leader Eduard Shevardnadze, who has no diplomatic experience, as foreign minister. Gorbachev has known Shevardnadze since their youth; they simultaneously headed the Komsomol organizations in their respective regions.

The pathway to power is designed for those who excel at loyalty and compliance, not intellectual curiosity.

While appointing an inexperienced Georgian is bold, Shevardnadze is hardly an outsider. He’s a longtime party apparatchik and a Politburo member candidate, with thirteen years as Georgia’s leader. Gorbachev isn’t yet ready to bring in true outsiders.

Gorbachev has no advisors from his pre–General Secretary days—no allies apart from his wife, Raisa. Moreover, he has no real ideological allies; the Soviet system is built on obedience, not personal convictions. The pathway to power is designed for those who excel at loyalty and compliance, not intellectual curiosity. Independent thought is seen as a liability; indeed, anyone with real principles would struggle to endure endless speeches praising the General Secretary, the party, and the greatness of Lenin. Successful party bureaucrats are experts in shutting off critical thinking, seamlessly agreeing with—and even applauding—whatever nonsense the elderly leaders say from the podium.

Throughout his career, Gorbachev excelled at playing this game. Only upon reaching the top does he realize that a General Secretary is expected to have his own opinion on everything.

He draws inspiration from a few sources. One is Vladimir Lenin. Gorbachev believes the USSR failed to build true communism because Lenin’s teachings were distorted and forgotten. A return to “pure Leninism” will, he thinks, set things right. This makes Gorbachev unique; while Soviet communists regularly cite Lenin, no one seriously reads him anymore.

Gorbachev, however, dives into Lenin’s complete works. Raisa’s friend Lidia Budyka recalls visiting the Gorbachevs and seeing Lenin’s volumes, marked with tabs and notes, on their table. Shocked, she asks if Gorbachev is truly reading them. He answers himself: “You know, Lidia, you should read Lenin’s correspondence with Kautsky. It’s better than any detective story.” In his public speeches, he emphasizes that he’s not reforming the Soviet system but rather restoring Lenin’s original vision.

Another source is Gorbachev’s own experience, and it’s a bit unusual. He spent most of his life in Stavropol, climbing the career ladder. He doesn’t have any close friends—no one from his old team followed him to Moscow. His only real advisor and confidante is his wife. They have a daily ritual: every evening after work, they take a walk together and Gorbachev tells her all about the political issues he’s dealing with.

Once he becomes General Secretary, Gorbachev starts looking for people he can work with comfortably—that’s how Anatoly Chernyaev ends up by his side. Chernyaev had been with the Communist Party’s International Department since 1961, writing speeches for Soviet leaders and managing relations with foreign communist parties. He was already fed up with much of his work, finding it mostly pointless.

Later one of Gorbachev’s acquaintances would put it like this: “He knew his wife wouldn’t go to bed with him if his hands were stained with blood.”

So when he hears about Gorbachev’s rise to power, he’s genuinely thrilled. He hopes it’ll bring a real change from the endless, empty quoting of Marxist-Leninist classics to something that feels like real life. And as he gets to know Gorbachev better, Chernyaev makes a surprising discovery: unlike most of his colleagues and predecessors, Gorbachev seems to get that the “hostile ‘imperialist world’” vilified by Soviet propaganda is actually just a complex web of different nations and societies, “clearly not preparing to attack or invade the Soviet Union.”

Chernyaev also notices something unusual about Gorbachev, maybe a trait he picked up from his philosopher wife: an “aversion to violence.” Later one of Gorbachev’s acquaintances would put it like this: “He knew his wife wouldn’t go to bed with him if his hands were stained with blood.”

Newly appointed General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev is eager to make a strong start, but he lacks a clear plan. He is largely aligned with Yuri Andropov’s recent approach: restore order and everything will fall into place. In March 1985, Politburo member and now the country’s second-incommand Yegor Ligachev presents an idea to quickly improve the situation. He proposes that the Soviet Union’s main issue is that people drink too much. Tackling alcoholism, he argues, would produce swift, visible results.

Ligachev is partly right. By the late 1970s, drinking has become almost a religion in the USSR. It is a way to escape the meaninglessness of the present and avoid facing reality. Belief in communism has long faded, yet everyone is expected to pretend otherwise. “It was marathon drinking,” rock musician Boris Grebenshchikov recalls, describing his lifestyle at the time. “I saved up money all week, bought a case of wine called ‘Bear’s Blood,’ and on Friday, we’d head to Vitya Tsoi’s place and get stuck there for three days.”

Statistically, the anti-alcohol campaign appears effective: birthrates rise, mortality rates decline, and the average life expectancy climbs to seventy years. But there are unintended consequences.

Gorbachev and the Politburo agree with Ligachev’s proposal. Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa, strongly supports the campaign, as her brother struggles with alcoholism.

Liquor and beer production is drastically cut, and vineyards in southern regions like Georgia, Moldova, Crimea, and Kuban are destroyed. Stores authorized to sell vodka and wine implement limited hours, often from 2:00 p.m.to 7:00 p.m. or even as short as 2:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. A popular poem of the time goes:

At five, the rooster crows, at eight—Pugacheva.

The store’s closed until two, the key is with Gorbachev.

Drinking on the job is now banned, restaurants and cafés stop serving alcohol, and public drunkenness can lead to fines or even job loss. Soviet censors joins the sobriety campaign, forbidding films, books, or plays that feature drinking.

The only opponents of the “dry law” are economists in the Council of Ministers. They quickly calculate that alcohol sales are a critical revenue source. In recent years, alcohol has accounted for up to 10 percent of the national budget. Any restrictions, they warn, will severely impact the economy. Gorbachev and Ligachev, however, deem these concerns “immoral,” insisting it’s unacceptable to profit from people’s drinking.

Statistically, the anti-alcohol campaign appears effective: birthrates rise, mortality rates decline, and the average life expectancy climbs to seventy years. But there are unintended consequences.

First, there’s a boom in home brewing. By 1985, sugar is in short supply across the country as people turn to home distilling. Second, the alcohol shortage drives people to consume substances like cologne and windshield cleaner. Another popular substitute is Moment glue, which becomes a substance of choice for Soviet teenagers to sniff.

Finally, the most significant outcome of the “dry law” is the unprecedented wave of resentment it generates toward Gorbachev. Following a series of lifeless predecessors, Gorbachev—a young, energetic figure—enjoys a tremendous reserve of public goodwill, and people want to like him. But the first thing he does in office is impose a “prohibition,” a deeply unpopular move that fails to address the core societal issues. If people drink to escape despair, banning alcohol may prevent them from drinking, but their despair remains.

Gorbachev will later recall that the first person to frankly tell him the “dry law” was a mistake was his mother. After becoming General Secretary, he visits her in Privolnoye, a village in the Stavropol region. She prepares a meal of borscht, homemade dumplings, and mineral water. “Not even a bottle of wine, Mother?” he teases.

She replies, “You know, Misha, someone decided people shouldn’t do that in this country. And I want to tell you it’s a bad idea. At weddings, people curse you. On birthdays, they curse you. I’m not putting anything out, because tomorrow people will say, ‘He’s allowed, his mother is allowed, but we’re not.’”

Thus, Gorbachev earns his first and mildest nickname from the public: the Mineral Secretary. The nicknames to follow will be far harsher.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Dark Side of the Earth: Russia’s Short-lived Victory over Totalitarianism. Copyright © 2025, Mikhail Zygar. Reproduced by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Mikhail Zygar

Mikhail Zygar is a journalist, writer, and filmmaker, and the founding editor-in-chief of Russian news channel Dozhd, which provided an alternative to Kremlin-controlled federal TV channels by giving a platform to opposition voices. The recipient of an International Press Freedom Award, Zygar writes a weekly column on Russia and the war for DerSpiegel and also writes for the New York Times, Time Magazine, Vanity Fair, and Foreign Affairs. He is also the author of All the Kremlin’s Men, The Empire Must Die, and War and Punishment. Currently a guest lecturer at Columbia University, he lives in New York with his husband.