On the Early Days of Life in the Sky as a Stewardess

How Ann Hood Took to the Air to Become a Writer

Men wore jackets and ties; women accessorized their outfits with matching shoes and handbags. I had to find something that made me look stylish, older, worldly. After many hours at the mall, I finally bought a one-piece shiny polyester jumpsuit, white with a fake inset blue-and-white polka dot blouse. White platform sandals. White hoop earrings. White clutch. How sophisticated I felt in that outfit! Like a person ready to see the world.

On board my Delta flight to Bermuda, I studied the stewardesses in their navy-and-red uniforms with white ribbed mock turtlenecks and wings pinned to their jackets as they moved about the cabin. I had wanted to be an airline stewardess since I was eleven years old and read a 1964 book called How to Become an Airline Stewardess, by Kathryn Cason. “The airline stewardess leads a life completely different from the routine of any other working girl,” Cason wrote. “Breakfast in New York on a winter morning and lunch in Miami under palm trees is all in a day’s work . . . Dinner could be in London, Amsterdam, Stockholm or Rome. Could be? It is, every day.”

For a girl growing up in a small, depressed mill town with outsized dreams, this sounded enchanting. Deep down, I wanted to be a writer, and writers, I believed, needed adventures. They needed to run with the bulls in Spain and jump into fountains in Paris. What better way to have adventures than being a stewardess and getting paid to have them?

Of course, on page 1, Cason also warns that in the airline industry, men write the rules and set the standards, do all the interviewing and hiring, and fill all the top jobs. “So face it from the start—you’ll never make a Vice-Presidency. But who cares? . . . [they] are running the biggest non-profit marriage market in America . . . the average stewardess keeps her job for 27 months. Within that time, 85% resign to marry!” Cason goes on to list the assets of girls lucky enough to become stewardesses—liking people, a friendly outlook on life, tact, and patience. “Now, when that kind of girl learns to cook too, what kind of man in his right mind wouldn’t rather see her standing in his doorway than an airplane?”

When I read these words as a seventh grader, they probably held little impact. Everyone I knew wanted to get married, sooner rather than later. Even girls my age practiced writing their names as “Mrs.” before the name of whichever boy they had a crush on. I’d watched my older girl cousins finish high school and maybe a two-year program in nursing or at Katharine Gibbs for secretarial training, then appear at our door to show off their diamond engagement rings and nervous fiancés. In no time, they walked down the aisle in complicated, beaded white gowns, we younger cousins in our own pink or maroon gowns and odd headpieces—giant bows or straw hats—trailing behind them. If this was our fate, why not marry one of those businessmen in the airline ads instead of the guy who sold us deli meat or fixed our cars?

I focused instead on all the cities Cason promised I’d visit, all the friendships I’d form, all the things I would learn about the big world out there beyond the factory roofs outside my window. But as the sixteen-year-old who boarded that Delta plane that summer morning, what did I think about the stereotypes of stewardesses? Of women in general? In the few years since I’d first read How to Become an Airline Stewardess, my attitude had started to shift. Did marriage have to be my fate? What would life be like if I didn’t get married and lived a single life in a fancy penthouse apartment in a big city somewhere? One of the reasons I broke up with my high-school boyfriend was a fear of stepping onto that marriage track before I had a chance to live my own life. In just five years, I would be the one in the uniform at the boarding door greeting passengers, hired at a time when perceptions of the job and women’s roles began to shift, as well as the start of airline deregulation, arguably the most crucial turning point for the airline industry.

But all of that lay ahead of me in the sunny, blurry future I imagined for myself. “Outdoors the sun is shining, the sky is clear and blue, the crew car is waiting, filled with girls, all young, all excited, chattering like magpies, with the whole world ahead of them . . . In you get and off you go,” Cason tells us at the end of the book. That first flight felt a little like that already. In you get and off you go.

Although I was an avid and indiscriminate reader, I somehow missed the Vicki Barr Flight Stewardess books of the late ’40s and early ’50s, which follow Vicki and her glamorous friends on adventures and dates. I also never read the 1951 Skygirl: A Career Handbook for the Airline Stewardess, written by Mary F. Murray with an introduction by the very first flight attendant, Ellen Church. Murray, the director of stewardess training at the Aviation Training School in Boston, wrote the book “for the girls who want to be airline hostesses and wonder whether they qualify.” She gives matter-of-fact information about everything from training, uniforms, domiciles, and even the drawbacks of the job, including smiling and poise that are “her most valuable asset.”

I did, however, read the 1967 bestseller Coffee, Tea or Me?: The Uninhibited Memoirs of Two Airline Stewardesses by the time I was sixteen. “Stewardessing is the ideal job for girls looking to travel and see other places, make many new and varied friends, feel at home in hundreds of strange cities, and get paid for these things to boot,” the narrator Trudy Baker tells us on the first page. Trudy Baker and Rachel Jones were actually pseudonyms for the ghostwriter, Donald Bain, an American Airlines PR executive.

The book is peppered with illustrations by Ben Wenzel of stewardesses in miniskirts and high heels being leered at by male passengers as they stuff men’s briefcases into the overhead bin, leaning over a grinning pilot with a large breast squashed against his cheek, or hanging out in cocktail lounges or fancy restaurants with cleavage spilling out of a tight-fitting dress. “A stewardess,” Trudy—Donald Bain—writes, “is a girl. She wears a uniform and works at thirty-five thousand feet. But above all she is a girl, female and subject to all the whims and desires of all females.” To Donald Bain, Ben Wenzel, and the book’s publishers, that meant stewardesses—and all “girls”—wanted to be ogled and objectified. When Trudy attempts to put a soldier’s bag in the overhead, her “pull proof” blouse pulls and reveals her bare belly. The soldier puts his nose in her belly button, and all Trudy thinks is, “It tickled.”

I had a grand plan. I would be a stewardess, travel the world, have adventures, and then write novels about my travels and adventures.

The stewardesses on my flight to Bermuda had big smiles and short, styled hair. To my relief, they didn’t match up with the buxom sexpots in Coffee, Tea or Me? In fact, they looked pretty wholesome, like me. One of the qualifications for being a teen model at Jordan Marsh, called a Marsha Jordan Girl, was a wholesome look. I wore my dirty-blond hair long and straight and, other than lip gloss for special occasions and Jordan Marsh fashion shows, didn’t use any makeup. Watching the stewardesses, I could easily see myself as one of them, and the thought thrilled me.

My excitement at actually flying was so great that I didn’t listen to a word they said over the intercom (until I actually went to flight attendant training myself, I thought there were parachutes under the seats). To my delight and surprise, after takeoff the stewardesses donned paisley aprons and appeared with full breakfasts for us—coffee, orange juice, scrambled eggs, sausages, and fruit. It was, I thought, the most delicious breakfast I’d ever eaten.

The list of everything I didn’t know on that first flight was long: I didn’t know there were two cabins, separated by a blue curtain, one rarefied and elegant and the other for everyone else; I didn’t know that while I ate my eggs and sausage there were people just a few years older than me behind that blue curtain, sipping champagne; I didn’t know what the life of a stewardess was really like—“Food under your fingernails, sore feet, complaints and insults,” as well as that “it was like going to graduate school for the world”; or which airlines flew where; or that this was not only the golden age of flying but also the golden age of airplane hijackings, with sometimes as many as two a day.

All I knew was that so far traveling was everything I’d hoped it would be, and more. And there wasn’t just the excitement of the flight itself, of looking down at clouds, but also the marvelous things at the airports—watching luggage drop onto the baggage carousel and slowly spin toward me, the people rushing past who seemed to being going somewhere, the line of taxis in front of the terminal waiting for passengers. Behind me were the days of overly chlorinated motel swimming pools; of hours in a smoke-filled car and soggy sandwiches from the cooler in the way-back. Getting on an airplane meant perfect trays of food and gentle Muzak in the background, playing cards with the airline’s logo on them, reclining seats and little jets of air tickling your face.

Just a few years earlier, all of us seventh graders at John F. Deering Junior High School were required to visit our guidance counselor, Mr. Stone, and tell him what we wanted to do after high school. It seems like a strange thing to do, but our answer shaped our future through high school. Combined with our IQ scores, whatever we announced that day—nurse, teacher, secretary, mechanic—tracked us toward either college prep courses or commercial courses that focused on typing, shorthand, bookkeeping, wood shop, and auto repairs.

Seventh grade was also the year our school allowed girls to wear pants to school. Our hemlines were getting shorter, and the administration instituted a policy for teachers to measure the distance between our hem and our knees. If our skirts looked short, we were ordered to climb onto a desk so the teacher could measure. More than three inches and we were sent home. It seemed that the world was changing, what with girls in pants and miniskirts, notebooks with peace signs on the covers, lava lamps and Make Love, Not War posters bought from Spencer Gifts at the newly opened mall.

Mr. Stone was young, maybe fresh out of college, with the mutton-chop sideburns and droopy walrus mustache that were so popular in 1968. All male teachers were required to wear suits and ties every day, and Mr. Stone always wore a brown corduroy suit, even in warm weather. When it was my turn to visit his office, he asked me what I hoped to do when I grew up. I was a straight-A student, the kid who always raised her hand in class, who joined clubs and started new ones, a go-getter.

I had a grand plan. I would be a stewardess, travel the world, have adventures, and then write novels about my travels and adventures.

“I want to be a writer,” I told Mr. Stone.

He looked baffled. “Ann,” he said, “people don’t do that.”

“Don’t do what?”

“Become writers,” he said. Although I didn’t understand it then, Mr. Stone was saying what anybody in my small mill town might say about becoming a writer: it was impossible. Writers came from different kinds of places, lived different kinds of lives.

I looked around his office. “Then how do we get all these books?”

Mr. Stone followed my gaze across the bookshelves. “All of those writers are dead,” he said.

Melville. Hemingway. Fitzgerald. He was right. After I died, someone would find my unwritten novels and I would be published posthumously, I thought, putting plan B in place.

“Then I want to be an airline stewardess,” I announced.

Mr. Stone peered out at me from behind his aviator glasses and said, “Ann, smart girls do not become airline stewardesses.”

But Mr. Stone was dead wrong. Some smart girls do become airline stewardesses. And writers. And after my first flight, I knew I would be one of them.

____________________________________

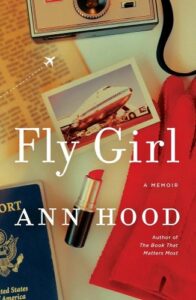

Reprinted from Fly Girl by ANN HOOD. Copyright © 2022 by ANN HOOD. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.”

Ann Hood

Ann Hood is the author of a dozen books of memoir and fiction, including the best-selling novels The Book That Matters Most and The Knitting Circle, and editor of the anthologies Knitting Yarns and Knitting Pearls. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island, and New York.