On the Dreams of Latinx Women in a Pandemic Year

Felicia Zamora Finds a Little Magic in a Dark Time

I find myself in wonder during this time of separation and distancing. We are all concerned for family, the people losing their jobs, concerned for healthcare workers, grocery store workers, workers in fields who can’t shelter in place, friends in New York, California, and other epicenters. State death counts are tallied like basketball points. Every time I turn on Netflix or Prime the most popular movies are Contagion and Outbreak. Americans, what are we doing to ourselves? I wonder which end of the kaleidoscope we are right now: the shifting geometric shapes and colors or the eye squinting to make sense?

I keep thinking about magic and the human ability to confront the unknown, about lineage and how alchemy lives in my tissues and finds its way into my bloodstream, my organs, my pulsating cerebrum. How is a dream a form of magic? The dream of Latinx women is a powerful brujería.

In the time of COVID-19, Trump, and children in cages, I turn to the necessary conjuring in my head, the act of self-creation that Latinx women must perform in order to survive despite our troubled histories and invisibility to this country. We push beyond stereotypes that we are only valued for hard labor, our bodies, and our blood rather than our minds, creations, energy, and wisdom.

I grew up estranged from my Mexican culture, living as a child with my white grandparents in Iowa. Our home was a 1950s-style motel; a converted diner held space for me, my two siblings, and my mother, in a town with no stoplights. It was a place where other people told me I was disgusting before I could discover myself. The place did not hold my future, but it was the only place I had to create a future from.

When I think about my past, I think of Carmen Giménez Smith’s words, “What is beauty I’ve been / asking since someone told me / I was/was not beautiful” (“Careworn Tale,” Cruel Futures) and I’m back in the Alden Motel. I’m standing between my grandfather and the television set. Perhaps I knew this was the only way to ever been seen by him.

In the face of historical colonization, Latinx women have turned to the magic inside us to help make sense of the world and to carve a place for us inside.“You’ll never amount to anything, you worthless little spic.” The first time my grandfather said these words to me, I was five. What really haunts me is not the racial slur or the violence of the words, but the absolute confidence in his voice. “In Mexico, the Devil is handsome / and smiles in all his photographs.” Diana Marie Delgado couldn’t be anymore correct (“Twelve Trees,” Tracing the Horse).

My grandfather knew nothing of my ability to conjure myself into existence. Language casts spells fueled by desire. Racism is an infection, but the magic of loving oneself is the antidote.

How is this violence different from that of a president who considers me a disgusting animal? How is this different from a society that doesn’t want me or my culture to have a voice? I was recently told that my presence was considered back of the house as in, not meant to interact with others, not meant to be seen. I’ve been living in a country that smiles for the camera but tears me down behind closed ballots.

We find magic in the ancestral heritage of many African American and Latinx peoples in America. In her poem “Tropical Depression,” Vanessa Angélica Villarreal wrote, “I inherit a palace of locked doors.” This speaks to the position of Latinx women in this country. We find ourselves in a constrained system that wasn’t designed with us in mind.

In the face of historical colonization, Latinx women have turned to the magic inside us to help make sense of the world and to carve a place for us inside. Marginalized communities have always been pushed to the fringes, but in doing so, we develop our own survival practices and tactics of reclaiming our lives.

Do I consider myself a healer? No. Do I consider myself a mystic? No. Do I believe in my magical powers to dream myself into being in a world that bruises and beats me? Fuck yes. I believe in magic because I am here. I believe in magic within me because no one expected me to be here, except me.

How does desire impact this magic? Eloisa Amezcua wrote, “I’m dangerous; there’s little left / inside this body— / that hasn’t wanted not to subtract / from the world.” (“Self-Portrait”, From the Inside Quietly). We are torn from our wanting: the desire to be of the world and not take from it, which is a lie of colonization (one of many).

Before the pandemic hit, another Latinx friend and I were talking about being ill. We both mentioned feeling overwhelming guilt and shame when we fall ill. Our minds and bodies shame us and give into the internalized oppression that we were meant for only work, because the stereotypes of being a “lazy Mexican” or as my grandfather said, a “worthless little spic,” still has hold inside our cells despite all the spells we cast.

I cast a spell that lets us lift the veil from the notion that this country was ever paradise.As Amezcua said, “I’m dangerous” and I feel this. I spend my existence fighting against oppression while still being tethered to it internally. Diana Marie Delgado wrote “This is how my mother taught me / the difference between desire and the sea, // one is always bigger.” (“Desire Is a Road”, Tracing the Horse).

Oppression is taught and transmuted by white supremacy. It’s a virus inside our systems. Despite the desires we have as individuals, our collective voices are the only way to end oppression and create a real type of freedom for all humans. We are our own cure. This is an election year. A pandemic year. A year without a clear sense of how our society will shift after this virus.

I cast a spell to keep us safe and opens our eyes. I cast a spell that lets us lift the veil from the notion that this country was ever paradise. I cast the spell, Vote Vote Vote, where 2020 does not replicate 2016. I cast a spell where language is more love, always more love. Emma Trelles wrote, “There is something all powerful and holy / about a cold orange. Imagine peeling / each day into one flawless strip” (“Nocturne in Parts”, Tropicalia).

We dare to make magic through our dreams; dreams become the spell we cast to be a part of this world, this life that continues to set barriers around who we are. Latinx women have always been the shapes and colors of the kaleidoscope—the evolutionary, the spirits who know what survival looks like, and we shift. Let us look to those who know magic during these troublesome times. Let us think and be thought of. Let us cast spells to a new future where each day is as holy as the strip of orange rind.

__________________________________

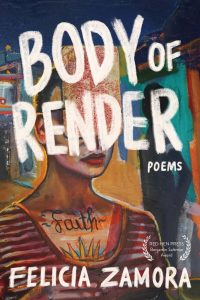

Felicia Zamora’s collection Body of Render is available from Red Hen Press.