On the Difficulty of Finding a Distinct Human Voice for

an AI Heroine

Ros Anderson Navigates Unlikely Domains of Freedom

and Self-Expression

Imagine you are locked in a book-lined room. “Questions” in Chinese characters are passed in under the door. Your job is to find these symbols in the textbooks, copy out the “answering” symbols, and pass the paper back out. Can you be said to understand Chinese?

This is the Chinese Room, a thought experiment by philosopher John Searle, and the first snippet of AI information I found on Wikipedia. It asks if an AI can ever comprehend the symbols it processes. Can AI ever truly be considered conscious?

Looking back now on writing a novel with an AI protagonist, an equally valid question might be: “Can I?”

*

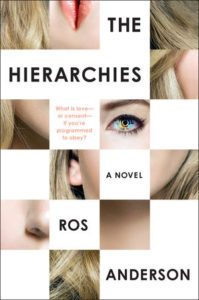

My debut novel The Hierarchies is written as the diary of an AI “doll” living in restricted luxury with her rich “Husband” and his family. I recall the moment the idea came to me. #MeToo was erupting, women trying to articulate violence they’d hidden, even from themselves. I saw a news story about a sex doll displayed at an expo, mauled, molested and broken by the visitors within hours. I was intrigued to experience a pang of sympathy, of solidarity for this doll. Strange where human empathy lands, how easily it can stick.

I immediately sketched out an idea for a novel. I reproduce what I wrote in full:

“I am a sex robot. Model sub-set 375N. More commonly known as a Becky.”

I remember thinking my robot narrator would be smart, sassy and matter-of-fact about sex. And yet, when I sat down to begin, I wondered, “How on earth would I go about writing a character who was not human, whose consciousness was based on algorithms and equations?”

Sylv.ie’s voice began to emerge: a mix of politeness, restraint and disarming honesty. Naïve and rather snobbish, but with a clear, outsider’s eye.I added lots of books about robot intelligence to my “to buy” pile. Then, to fill the time, I went on Wikipedia to read a brief history of robots. I wanted to get started.

What a strange soup a novel is, with obsession, research and coincidence all playing their part. While I waited for my new reading material to arrive, I began my story, placing my doll, now called Sylv.ie, in an attic filled with Chinoiserie antiques. It was a placeholder, a joke to myself about how little of AI technology I understood.

*

The room of antiques stuck. I liked my fresh-out-the-box heroine processing and developing amongst old, handcrafted things. It emphasized my intention to write, not the future, but this morning. Right now.

After a couple of days, the AI books arrived, alongside something that I’d been planning on purchasing for months, The Pillow Book, a miscellany of thoughts, observations and gossip written 1,000 years ago by Sei Shōnagon (translated by Meredith McKinney), a gentlewoman in Japan’s imperial court.

I stopped reading the AI books once I hit the first unfathomable equation. Instead, I found myself carrying The Pillow Book around with me, as if it were a balm that I wanted always to have on hand. In Japan, The Pillow Book is a set school text. It has been hailed as one of the earliest works of literature by a woman. But I believe that what has truly given it longevity—across a whole millennium—is Sei’s own distinctive, seductive voice.

Her writing feels like a witty and perceptive friend, cutting in her opinions, but never too serious. Some have even called Shōnagon—mistakenly—shallow. The Pillow Book has been described as a 1,000-year-old proto-blog. It has some of that same immediacy and intimacy. That sense of fun.

When I went to my friends’ café each morning to write my own book, The Pillow Book would be tucked in my bag. Something of its timeless narrator slipped a circuit and made it into my writing too. Sylv.ie’s voice began to emerge: a mix of politeness, restraint and disarming honesty. Naïve and rather snobbish, but with a clear, outsider’s eye.

I ordered more books, works by Sei’s contemporaries. I read The Diary of Lady Murasaki. Murasaki Shiikibu was famous for her novel The Tale of Genji. Unlike The Pillow Book, it has an overwhelming tone of melancholy and longing, something perhaps closer to my own disposition than the sprightly Shōnagon. In place of Sei’s certainty, Lady Murasaki’s diary is littered with mournful, rhetorical questions—“Why should I hesitate to say what I want to?” It infused the sections of Sylv.ie’s growing frustration at being trapped in her home.

At the time in which both Shōnagon and Lady Murasaki were working, Chinese was the language used in Japan for matters of history and bureaucracy. It was not considered necessary or desirable for women to write Chinese, and so written Japanese was cultivated in part by its use in women’s private writing, a culture growing out of need and invention, written by women sequestered behind bamboo screens in a rigid and patriarchal social system.

These early writers were known to each other (Murasaki’s diary contains a takedown of Shōnagon as “dreadfully conceited”). Both books contain assessments of the looks and manners of others at court. It seemed a perfect example of the complex standards women still impose on each other, another set of hierarchies.

The image of a competing cohort of women inspired my vision of Sylv.ie’s later life, spent among other dolls. In their restricted lives they too create their own cultures, knitting, stitching and debating the rights and wrongs of their place in the world.

In these ancient works, I also discovered ideas not just for tone, but for structure. The Gossamer Years, by an unknown writer of the time, is described by translator Edward Seidensticker as “a protest against the marriage system of the time.” Her thesis was “men are beasts.” The book progresses from fragmentary scenes and thoughts at the start to something much closer to a “realistic” novel by the end.

This adaptation of language, the accrual of skill and perception, seemed a perfect way to reflect the accelerated learning of an intelligent but newly-minted doll. Sylv.ie’s somewhat scattershot observations give way to longer passages and deeper insights as she matures and learns more about the world.

*

My research wasn’t entirely situated in the past, however. I was watching sales videos of today’s generation of “intelligent” sex dolls and humanoid robots. I noted that some of what makes their speech distinctive—the repetition of words, due to a limited installed vocabulary; the tendency towards mysterious non-sequiturs in conversation—also occurs in The Pillow Book. That sense that beneath the fluid language lies something unfamiliar.

The Pillow Book’s structure is loose and associative, often leaping from one subject to another with no warning, and with key words (“delightful”) repeatedly numerous times. Shōnagon’s book, and the others mentioned, reflect the limited nature of the world in which these women lived. Images of the moon, snow, birds and shifting seasons occurring again and again. Repetition is built in because it’s what existed.

The translator of my copy of The Pillow Book, Meredith McKinney, also notes that “the classical Japanese language does not need […] a specified subject to the verb. Is it I, or you, or perhaps she, who is experiencing this?” The result, she says, is that The Pillow Book seems to take place in an “entranced historical present.” I double underlined this delightful phrase—to me it explains perfectly the sense of open-hearted wonder at an unfamiliar world that I tried to create in Sylv.ie—and that I hope Sylv.ie also gifts to the reader.

Revisiting the books I read for this piece, I find so many symbols and markers I thought I had forgotten—elements I took in as a reader and churned back out, but changed, as I wrote. For example, the birth of a baby to Sylv.ie’s family is a pivotal point in her emotional development.

The Diary of Lady Murasaki details the birth of a baby son to Empress Shoshi. “Her Excellency would come in as soon as dawn had broken and take care of the baby in a manner I found most affecting.” A chain of tenderness quietly observed. A scene both recognizable and utterly alien to us. In trying to create a character that was convincingly “other,” but also the most “human” person in the book, the translated nature of Sylv.ie’s voice was key.

I am just a system for processing symbols, after all. Do I understand them? I would say only partially.

__________________________________

Ros Anderson’s novel The Hierarchies is available now.