On the Destruction of the Deep Earth as a Destruction of the Self

Justin Hocking Explores the Legacy of Project Plowshare and Nuclear Testing in the American West

It begins as a low rolling rumble, like a train off in the distance.

My father sits on a wooden bench outside the ranch house, pulling on cowboy boots, whistling Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings tunes. Colorado sun warm on his cheeks, his square chin.

The rumbling stirs the horses; the dogs whimper and cower beneath the porch, like when a wolf stalked the property, months before.

Seconds later it reaches him like a minor earthquake, like subsurface thunder.

My father stands.

My mother’s inside, holding her pregnant belly while sitting on the edge of the bed, which by now rocks violently, nearly throwing her to the floor. She calls out my father’s name, “Roger?”

“Roger” can be used as an affirmative, as in Roger that. My mother’s usage is just the opposite.

Our Western inheritance, then: the concept of the deep underground as wasteland, dump, terminus of the unredeemable.

*

On screen: a small, earthy mound rises from the ground, a slow-motion birth. A male voice with a smoker’s timbre and crisp enunciation narrates the documentary film, shot in the 1960s as a propaganda campaign for Project Plowshare. “To perform a multitude of peaceful tasks for the betterment of mankind,” the narrator explains, “man is exploring a source of enormous, potentially useful energy: the nuclear explosion.”

On screen, the mound expands into a steep, swollen hill.

Plowshare: an agricultural implement for turning soil, for gouging a cleft in the earth. The archetypal idea of the plowshare derives from the Bible, in which the prophet Isaiah urges the people to beat their swords into plowshares.

On screen, the hill grows into a mountain, and then the mountain—which is not a mountain—erupts, a hulking black mass edged with feathery projectiles, a pyrotechnic finale of soil and shale.

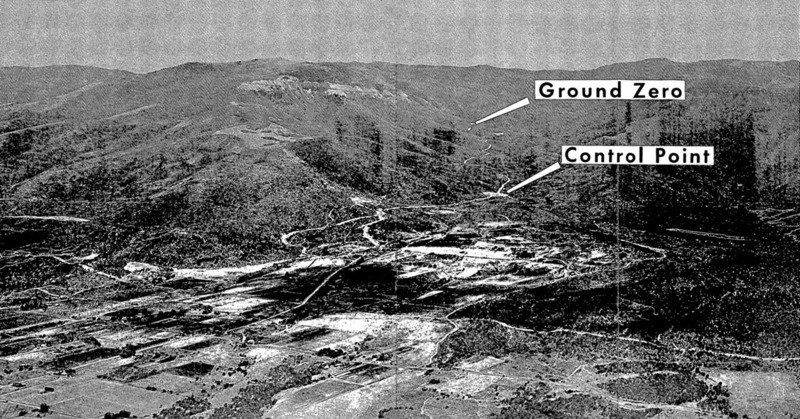

Under the auspices of Project Plowshare, scientists, engineers, miners, and military personnel detonated twenty-seven nuclear warheads in subterranean shafts of various depths across the continental United States. The project lasted seventeen years, from 1965 until 1973—the year of my birth. “For the benefit of all nations,” the narrator explains.

Lewis L. Strauss, chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, supervised Plowshare. Strauss was the man responsible for stripping J. Robert Oppenheimer, co-inventor of the atom bomb, of his security clearance. In Strauss’s opinion, Oppenheimer’s increasing concerns about nuclear proliferation and radioactive wastes were pedantic, alarmist.

Strauss and his Plowshare operatives had colossal ambitions. They envisioned large-scale nuclear excavation and quarrying: canals, railroad cuts through mountains, dam construction. They hoped to blast a harbor-sized hole in Cape Thompson, Alaska, and hack a channel through an oceanic reef in the Marshall Islands, all to enhance commerce and transportation.

Their grandest plan: to supplement or even replace the Panama Canal. Four possible routes across Central America were selected and studied. In the Plowshare film, a crude animation illustrates a zipper of nuclear blasts from the Atlantic to the Pacific, to excavate a sea-level channel up to two hundred feet wide and one thousand feet deep, an oceanic superhighway across Costa Rica or Nicaragua. Here are Le Corbusier’s and Robert Moses’s visions for unimpeded industrial transportation writ large—a freeway in the sea, a tainted slash across the American continent.

Another Plowshare application involved underground engineering and extraction of natural gas and petroleum. Nuclear fracking, in other words. Operation Rio Blanco was designed for this purpose, to frack a vast pocket of natural gas, just thirty miles from my parents’ house.

*

The Christian concept of hell has origins in the New Testament, where it’s described in the Greek as hades or with the Hebrew word gehenna. The actual gehenna was the “Valley of Hinnom,” a garbage heap in a low ravine on Jerusalem’s outskirts. A place where refuse was burned. Bodies of suicides were thrown in, to smolder with the muck and char. Authors of the New Testament use gehenna as a metaphor for the final place of punishment for the damned. A linear narrative: hell as perpetual destination, endpoint, a fiery conclusion. The place where Dante cast endless sinners, upside down in hellholes of their own carving, or in the tangled forest of suicides, or with the fratricides in the ninth circle, all of them eternally condemned.

Our Western inheritance, then: the concept of the deep underground as wasteland, dump, terminus of the unredeemable.

*

Western Colorado towns named for their mineral wealth: Crystal, Marble, Redstone, Gypsum, Silverton, Silt, Copper Mountain, Leadville. New Castle, Colorado, was named after New Castle, England—a historic coal-producing city. On my father’s side, Hocking ancestors originated from Cornwall, England; some were fishermen, but most made their living as coal or tin miners, in the epicenter of industrialized mining.

Four years after they married, my parents bought a small ranch outside Silt, across the Colorado River and south of New Castle. My father wasn’t a miner himself, but as a civil engineer he made structural plans for tunnels and sewers—underground work. And like generations of Hockings before him, he pursued mineral wealth. In his case, the early 1970s boom in the oil shale industry on the Western Slope attracted him. He performed surveys for infrastructure around local oil operations; he engineered sprawling man-camps to house shale miners. Eventually he launched his own successful firm and named it El Dorado Engineering, after the mythical city of gold that enticed Spanish conquistadors to the new world.

My parents fixed up the modest ranch, mended fences and corrals. They raised horses and an Australian shepherd with one brown and one crystal-blue eye. Regular visitors to the ranch: coyotes, elk, foxes, crows and hawks, and once, a wolf. The wolf kept his distance, but drove the dogs half-mad with fear.

They looked forward to their first child—especially my mother, who worked shifts as a maternity ward nurse at Valley View Hospital. By April of 1973, they’d decided on my name. My mother was a careful parent. Avoided alcohol, ate carrots and lettuce and tomatoes from their garden plot. At the small diner in Silt, she sometimes asked ranchers and miners at neighboring tables to extinguish their cigarettes. This embarrassed my father, a man who prided himself on not letting things bother him.

No one had thoroughly informed my parents about the nuclear testing, but among the residents of Silt, Project Plowshare was common knowledge. The Rulison test, in which the government detonated a single forty-three-kiloton nuclear bomb below ground just twenty miles from town, took place four years earlier, without fanfare. The Rio Blanco test of 1973—wherein Plowshare operatives planned to ignite three nuclear warheads a mile beneath the surface—was just another subterranean exploration in an area developed largely for the purposes of mining.

Everyone knew it was coming.

*

Linear versus cyclical narratives: in some Indigenous cultures, hell is an intermediary period between incarnations or stages. Many have no concept of hell; they view the underground as a place of ritual, transformation, and even genesis. Modern Puebloans—whose forebears may have hunted on the high deserts around the Rio Blanco nuclear test site—believe their ancient ancestors first emerged from the underworld. They commemorate the emergence with a small hole in the floor of their kivas called a sipapu—a symbolic portal to the birthplace of their people.

*

In the Project Plowshare film, the narrator acknowledges the problem of radiation, and problems other than radiation: the groundshock, the airblasts, the dustcloud. Fundamental distinctions: earth as a womb, or earth as a tomb of eternal punishment. The underground as an origin point, a sacred realm, versus the underground as a site to exploit, carve up, burn. James Watt, secretary of the Interior under Ronald Reagan, was a fundamentalist Christian known for his extractive boasts: “We will mine more, drill more, cut more timber…” He believed large-scale strip-mining of the West was acceptable because the Rapture was imminent.

*

Craig Hayward was eighteen when he witnessed the Rulison nuclear shot. He was the grandson of the rancher who leased the land to Project Plowshare. The U.S. government promised the Hayward family a share in revenue, should the nuclear method prove viable for fracking natural gas.

I was still in the womb; I saw nothing of Project Plowshare. But was I curious and disturbed, even then, by what took place beneath the surface?

“When they touched that thing off, I saw shale cliffs crumbling,” Hayward said. “After a while, I saw the ground rolling. It was like a wave coming through. Cars were parked there. They were rocking back and forth.”

A small group of protesters gathered near the detonation zone. They feared polluted groundwater, contaminated natural gas seeps, radioactive nucleotides with a half-life of a quarter of a million years. As current landowners near the Rulison site still worry, fifty years later, when energy companies drill for natural gas just miles away.

*

The 1959 film Hiroshima Mon Amour, by French director Alain Resnais, explores the entangled nature of personal and historical memory; it’s shot in an experimental style that cracks apart the genres of fiction and documentary and smelts them into a ghostly, shimmering amalgam. Jean-Luc Godard described Hiroshima as “Faulkner plus Stravinsky.” The mostly impressionistic plot centers a French woman visiting Hiroshima to film an anti-nuclear war film—a postmortem attempt at documenting Japan’s holocaust. There she has an affair with a Japanese man; both are married, both still traumatized by war. Though she attempts to comprehend the Hiroshima bombing by visiting a museum and interviewing survivors for her film, her Japanese lover tells her repeatedly that she “saw nothing of Hiroshima.” Susan Sontag dubbed Resnais’s work “the cinema of the inexpressible.” Other critics point to Hiroshima Mon Amour as the epicenter of postmodernism. It’s about the hopeless inability of a museum—or any conventional, linear narrative—to convey the lived experience of such cataclysmic trauma.

But what of the three nuclear bombs buried and detonated near your family’s home, two and a half months before your birth? There were no mass casualties, no immediate human casualties at all, so perhaps narrative is up to the task. But wouldn’t the explosion cause the story itself to rock and fracture like those crumbled shale cliffs?

*

The Rio Blanco nuclear shot stimulated a flow of natural gas, as hoped, but the product was contaminated with radioactivity. Unusable. Just as it was in 1969, after the Rulison test.

After twenty-seven nuclear shots, Project Plowshare began losing popular support. Activists deemed the blasts and their aftermath an environmental catastrophe. Among politicians, the idea of using nuclear weapons to build a better Panama Canal was seen as increasingly preposterous.

Seventeen years after Plowshare’s genesis, Rio Blanco marked the very last underground detonation. The endpoint of the project’s linear narrative.

*

I want to believe that, during the Rio Blanco test, my mother felt an internal rocking—the child inside her growing restless, uneasy. Perhaps in reaction to her own physiological stress response. Elevated heart rate, adrenaline spike as the ground shook beneath her—the result of a nuclear blast six times as powerful as the Hiroshima bombing.

I was still in the womb; I saw nothing of Project Plowshare. But was I curious and disturbed, even then, by what took place beneath the surface?

__________________________________

Excerpted from A Field Guide to the Subterranean: Reclaiming the Deep Earth and our Deepest Selves by Justin Hocking. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.

Justin Hocking

Justin Hocking is the author of The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld: A Memoir, which won the Oregon Book Award and was a finalist for the PEN Center USA Award for Nonfiction. He served as the Executive Director of the Independent Publishing Resource Center (IPRC) from 2006–2014 and is a recipient of the Willamette Writers Humanitarian Award for his work in writing, publishing, and literary outreach. He teaches creative writing in the MFA and BFA Programs at Portland State University.