On the Death of Tech Idealism (and Rise of the Homeless) in Northern California

“It’s as though the city feels it’s been invaded by the unhoused. But turn San José inside out and it’s a giant homeless camp being invaded by a city.”

Fuckers. I couldn’t get the word out of my head, because he wouldn’t stop saying it. I was sitting in the tiled courtyard of the Mediterranean-style home of an old acquaintance, a venture capitalist and serial tech entrepreneur, who lived a few blocks from Zuckerberg in Palo Alto. Next to us was a massive stone slab over which water dribbled into a reflecting pool. A Buddha sat on the stone, contemplating the flow. Above us sprawled the canopy of a century-old olive tree, which had been raining its fruit onto the courtyard.

It would have been an idyllic scene, were it not for the presence of my acquaintance, who kept smacking and berating his dog, a puffy, pure-white Alaskan-looking thing, who wouldn’t stop eating the olives.

In my previous career, I was a landscape designer, and this person was my client. I’d lived in Santa Cruz then, a hippie-surfer town about an hour away on the other side of the mountains that separate the Valley from the ocean. I was not alone in commuting over those mountains—many of Santa Cruz’s hippies and surfers make the trek to stick their straws where the wealth is. I went to college at the University of California in Santa Cruz—home of the fighting Banana Slugs!—and spent the entirety of my twenties there.

When I drove over after arriving in Cupertino, however, a camp lined the main road into town; hundreds of unhoused residents inhabited another area along the river.

When thirty approached, I began to think of things like owning a home, which even an hour from the Valley’s gravitational center was out of reach with my income at the time. So a few months after the Great Recession hit, I moved back to Georgia, where I’d grown up. I bought a house on seven acres for $90,000.

I’d been away from California for twelve years. Much had changed. The real estate costs I’d fled had tripled; 2008 prices now seem quaintly affordable. I don’t remember ever seeing a tent on the streets of Santa Cruz back then. It was known as a place with a lot of panhandlers and drug users, but not so many that they made their dwellings in places obvious to the casual observer. When I drove over after arriving in Cupertino, however, a camp lined the main road into town; hundreds of unhoused residents inhabited another area along the river.

My client had also changed. I remembered him as a charming, progressive guy, but he’d grown older, crankier, and more libertarian in the decade since I last saw him. Apparently he’d become fond of calling people fuckers, and when I broached the topic of homelessness, he erupted in a lava flow. Employees of NGOs who concoct idealistic plans to address the housing crisis? Fuckers. Activists who valiantly defend the less fortunate among us? Fuckers. He couldn’t stand to go to San Francisco anymore because of the hordes sleeping and shitting right there on the sidewalk, in front of businesses run by people who actually contribute to the economy.

“If we can figure out how to get a package from China to your doorstep in two days, we can figure this out,” he said. Whether it’s houses made of shipping containers or building artificial islands in the Bay to house the homeless, he assured me that “innovators” like himself could come up with a solution—if only the incompetent, na.ve, and corrupt fuckers in the public sector would get out of the way.

In fact, he would personally love to dig his entrepreneurial hands into the issue. But the poverty space was dominated by inefficient nonprofits and he wouldn’t waste his time consorting with them—the profit motive is what drives efficiency, after all, and efficiency paves the way to viable solutions. Nonprofits are in the business of self-congratulation, not getting things done, he said. His evidence: They hadn’t fixed the problem yet. “It’s like a car or your phone,” he said. “Either it works or it doesn’t.”

The last time I’d seen my client he was plotting his first trip to Burning Man. He’d shown me some of his paintings and we’d chatted about organic farming and his time in a kibbutz. Though he worked sixteen hours a day (he claimed to sleep no more than a few hours a night), he nevertheless found time to feed his omnivorous intellect, which snacked on cybernetics and chewed on transcendentalism after dinner. He was the archetypal boomer tech entrepreneur, kissed by the antiestablishment, but in the business of re-establishing the establishment in his own image.

The Valley overlaps geographically with the hippie homeland of San Francisco, Berkeley, and their environs, and there’s long been cross-pollination, if not orgiastic copulation, between the two spheres. As a barefoot college dropout in the early seventies, Steve Jobs’s interests included Ram Dass, Hare Krishnas, and fruitarianism; his connection to apples stemmed from a stint at the All One Farm, a commune where he worked in a Gravenstein orchard.

The commune fell apart as residents realized they were being conned by the spiritual leader, a close friend of Jobs, into providing free labor for his apple cider business. The apple cider guru later became a billionaire mining magnate notorious for labor and environmental abuses. Jobs, however, sought to bring his spiritual values with him in founding a company to disseminate what he considered the ultimate tool of enlightenment—the personal computer—to the masses.

This trajectory is such a prominent feature among the Valley’s founding fathers that it has spawned a minor field of academic study. “To pursue the development of individualized, interactive computing technology was to pursue the New Communalist dream of social change,” writes Fred Turner, a Stanford historian, in his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism.

Turner’s book focuses on Stewart Brand, a Merry Prankster turned evangelist of enlightened capitalism, who once roamed from commune to commune selling back-to-the-land supplies out of his 1963 Dodge truck. The Whole Earth Truck Store, as he called it, morphed into the Whole Earth Catalog magazine, which begat the Whole Earth Software Catalog, which begat Wired magazine.

Unhoused communities don’t randomly burble up from the sidewalk. They are born of the housed communities around them, which in the Valley’s case is a particularly curious one.

Brand, writes Turner, “brokered a long-running encounter between San Francisco flower power and the emerging technological hub of Silicon Valley,” in which “counterculturalists and technologists alike joined together to reimagine computers as tools for personal liberation, the building of virtual and decidedly alternative communities, and the exploration of bold new social frontiers.”

One can imagine a young Steve Jobs digging the communalism of today’s Bay Area camps, whose countercultural idealism shares many threads with that of the Valley’s early hippie-nerds—ironic given the bulldozing of camps in the shadows of contemporary tech campuses and their tightly conformist corporate cultures. The commonalities don’t stretch very far: A rather thick thread in the hippie-techie braid is individualism, a whole lot of which hid behind the Me generation’s “New Communalist” movement. The marriage of these Bay Area cultures is alive and well, but today has more of a New Age–Burning Man vibe.

Brand, now in his eighties, is an ardent Burner. He’s gone from libertarian to the even-harder-to-define “post-libertarian” and is building a five-hundred-foot clock inside a Texas mountain owned by Jeff Bezos, which is designed to tick once per year for ten thousand years. A cuckoo will emerge at the end of each millennium.

Brand shares a certain intellectual hubris with my acquaintance, who asked if I would like to read an eighty-two-page white paper he wrote regarding the human brain and why Darwin’s survival-of-the-fittest theory applies not just to biological evolution, but to the optimization of social structure. I stared at the Buddha and tried to think of a way to change the subject.

Unhoused communities don’t randomly burble up from the sidewalk. They are born of the housed communities around them, which in the Valley’s case is a particularly curious one. The Valley’s valley is wide and smoggy enough that some days you can’t see the mountain ranges that form it. The scorching Diablo Range, where cattle roam oceans of desiccated grass, lies to the east.

On the other side, the lusher Santa Cruz Mountains, a place of dank redwood forests, organic farming communes, and uppity vineyards, form a verdant curtain between the Valley and the ocean. Here the tech elite build their villas and take to the fog-kissed ravines for athleisure-clad recreation.

The valley started to become the Valley in 1943 when IBM opened a factory to manufacture punch cards in San José. At the time, orchards carpeted much of the region. When the trees blossomed in early spring, the honey-scented flowers intoxicated bees and lovers alike. During the late summer harvest, the air was a punch bowl. Maps referred to it then as the Santa Clara Valley, but romantic minds of the day christened it the Valley of Heart’s Delight, after a 1927 poem by a local writer with Wordsworthian sensibilities, named Clara Louise Lawrence.

No brush can paint the picture

No pen describe the sight

That one can find in April

In “The Valley of Heart’s Delight.”

Cupertino did not exist back then. The Glendenning family farmed the land where the Apple Spaceship now sits. Prunes were their specialty. The farm was on Pruneridge Avenue—the valley was considered the prune capital of the world, supplying 30 percent of the global market—which passed through their orchards near the present location of Steve Jobs Theater, a smaller circular building next to the mothership.

But Apple bought the road from the city—$23,814,257 for a half mile—so you can’t drive through there anymore. Between the steel bars of the fence you can still catch a glimpse of the Glendennings’ old fruit-drying barn, which has been renovated and is now storage for landscaping equipment. The new orchards and the old barn help soften the Pentagon vibe with a little farm-to-table ambience.

The Valley’s valley is not a stereotypical one because it lacks a mighty river meandering between the mountain ranges. Instead, there is the southern leg of San Francisco Bay, a shallow, brackish estuary fed by measly creeks that barely run in the dry season. It’s a bird and crustacean paradise, but the lack of fresh water and ocean currents make for a putrid aroma that’s further intensified by the landfills, wastewater treatment plants, and commercial salt-harvesting operations clustered around the waterfront.

The smell is so intense that it’s spawned a South Bay Odor Stakeholders Group “dedicated to identifying and resolving odor issues.” One finds Reddit threads with titles like South Bay Fucking Smell: “south bay people, you know what i mean. where the fuck is this rancid ass smell coming from. it’s pretty common for it to smell like shit here, i’ve smelled it my whole life, but i just want to know where it’s comin from. My guess is the shitty salty shallow south bay water spewing out smelly air, but idk.”

“That, or else it’s your mom,” replied another user, who referred to the odor as “the ass cloud.” The poetics of the region have shifted since Lawrence’s day.

The military forefathers of the Valley must have been horrified at the hippies their children became, though by the eighties the arc of flower power had bent toward the common ground of Wall Street.

The ass cloud did not dissuade the early tech settlers, who followed the money flowing from the patron saint of the Valley’s venture capitalists: DARPA, the Department of Defense’s secretive research agency, which commissioned much of the basic science from which the IT revolution sprang. While farms like the Glendennings’ continued to pump out prunes on the arable land between the Bay and the mountains, the military-industrial complex set up along the mud flats. The Navy built an eight-acre dirigible hangar in Mountain View, still one of the largest freestanding structures ever erected. The CIA quietly rooted itself among the reeds and spread rhizomatically. During the Cold War, aerospace companies blossomed between DOD installations. Lockheed was the Valley’s biggest employer when Kent and Steve Jobs were growing up in the suburbs that slowly consumed the orchards.

The American tech industry was born in the Bay Area because its defense industry parents came here to ward off the Japanese—during World War II, this was the gateway to the “Pacific Theater,” as the Asian front of the war was euphemistically referred to. This first generation of the Valley “seeded companies that repurposed technologies built for war to everyday life,” writes Margaret O’Mara, a tech industry historian. “Today’s tech giants all contain some defense-industry DNA.”

Jeff Bezos’s grandfather, for instance, was a high-ranking official at the US Atomic Energy Commission and at ARPA, the precursor to DARPA. Jerry Wozniak, father of Apple’s other Steve—Steve “The Woz” Wozniak, the company cofounder and part of the gang tweaking on computers in the Jobs’ garage—was an engineer at Lockheed. The military forefathers of the Valley must have been horrified at the hippies their children became, though by the eighties the arc of flower power had bent toward the common ground of Wall Street.

The Navy’s dirigible hangar still looms over the Bay, but Google now rents the property from the government for the parking of private jets. The company dominates the neighborhood to the west of the hangar, a spread of dull office buildings revolving around the central Googleplex, with its employee swimming pools, volleyball courts, and eighteen cafeterias. There are no houses or apartments in the neighborhood, though there are residential districts—of a sort. These are surprisingly affordable, which means that some of the folks who smear avocado on the techies’ toast and stock the kombucha taps have the good fortune to live nearby.

It’s easy to miss their humble abodes, however. An out-of-towner who gets off at the Google exit to take a leak could be forgiven for thinking they’d stumbled across some sort of RV convention. But those aren’t recreational vehicles lining the backstreets of the Google-burbs—those are homes on wheels.

RVs parked on the side of the road are the new desirable real estate, and like the old industrial cores of American cities that have evolved from roughshod hangouts for unemployed artists to haute loft developments for upwardly mobile professionals, their inhabitants aren’t immune to class stratification. Most of the rigs are older, ramshackle models, but here and there shiny coaches broadcast the relative wealth of their inhabitants—techies who could afford an apartment but don’t want to waste their money on rent.

They roll out of bed, hop on a company bike, and are at the office in three minutes, in the meantime saving up for a big house in the outer, outer, outer burbs, where you can still get a McMansion for under $3 million. Some already have the McMansion and use their RV as a workweek crash pad.

The more-rickety RVs belong to the avocado smearers and lawn mower operators. Crisanto Avenue, five minutes from the Googleplex, is the Latin America of Mountain View’s homes-on-wheels community. It’s like a museum of 1980s RVs—Toyota Escapers, Winnebago Braves, Chevy Lindys, Fleetwood Jamborees—most of them emanating Spanish banter, many with blue tarps over the roof, and some leaking unmentionable juices from onboard septic tanks. Apartments line one side of Crisanto, but the side with the RVs fronts onto train tracks. A shaded strip of earth along the tracks, maybe twelve feet wide, serves as a communal front yard, complete with potted plants and patio furniture, for pets and kids to play.

She’d held America in high esteem before living here. “La vida en los Estados Unidos es terrible,” she said.

An older Peruvian woman named Ida invited me into her RV, where a half-eaten pineapple sat serenely on an otherwise empty table. She used to live in a two-bedroom apartment with sixteen other people—“Fue imposible!” she said—until she learned of the RV scene. She couldn’t afford to purchase one, but there’s a growing industry in the Valley for old-school RV rentals; residents on Crisanto told me they pay between $500 and $1,000 per month, depending on the RV, plus a $75 fee to pump sewage.

Since Ida arrived in the US in 2003, she has worked mainly as a nanny, often for around six dollars per hour. Work was sparse during the pandemic, so she accepted whatever pay she was offered. One family gave her twenty dollars for taking care of their two children for twelve hours. She’d held America in high esteem before living here. “La vida en los Estados Unidos es terrible,” she said.

My visual experience of the Valley began to shift. My eyes had once flashed at views of the water, clever billboards (“Hey Facebook, our planet doesn’t like your climate posts”), and homes with the billowy, buff-colored grasses and scrawny wildflowers that signify the aesthetics of people who can afford expensive landscaping designed to look feral.

But the more time I spent with the Valley’s have-nots, the more my focus became trained on the visual language of the income inequality ecosystem: the camouflage patterns of desiccated vegetation pocked with blue tarps and plastic bags flapping in the branches; the hulking silhouettes of recreational vehicles parked in non-recreational environments; the bodies splayed out on the sidewalk.

Here and there, artistic aberrations emerge in the motif. I met a thirty-year old man named Ariginal who lived with his family and dogs in a 1983 Chevy camper van that he’d hand-painted marine blue with school-bus-yellow trim. A blue neon light mounted to the undercarriage illuminated the street in a cool glow as they motored around in their Scooby-Doo mobile at night. Ariginal went to school to be a fireman but became an Uber driver. He’s also a rapper, fashion model, and inventor—there are a few things he’s hoping to patent, and he wanted to show me the drawings, but his daughter was napping in the van. “I have a lot of dreams,” he said.

Within twelve minutes of meeting Ariginal I learned that he recently “discovered a couple of lumps . . . uh, in my testicles.” They were cancerous. He’d just had the tumors removed and would soon be undergoing radiation to make sure they don’t come back. “Just another obstacle,” he sighed.

“Vanlife has become the norm here,” a veteran gig worker named Chase, who’s driven for Uber, Instacart, and Amazon Flex, told me. He was not talking about hipsters who move into a home on wheels because it sounds like a fun and Instagrammable lifestyle. He was referring to his colleagues who have no other choice.

I found there is significant overlap between the gig work community and the unhoused community. Some full-time gig workers end up living in their vehicles; some camp residents become part-time gig workers because it’s a way to make a buck that doesn’t require a home address or the scrutiny of a human boss, only a working phone. Rudy, for instance, began delivering for food apps—using Lime scooters he rents by the hour—after he became homeless.

Their camps keep getting razed, but like the marshland reeds, they sprout right back.

The mobile communities stretch along the Bay up to Meta’s headquarters at 1 Hacker Way, on the outskirts of Palo Alto. East Palo Alto, the historically Black community surrounding the Meta campus, is one of the least gentrified, most impoverished places in the Valley—a 2017 study found that 42 percent of students in the local school district were homeless. A sixty-acre nature preserve across the street from the Meta campus is home to endangered species such as the salt marsh harvest mouse and Ridgway’s rail, a chicken-sized bird with a long, pointy beak and special glands that allow it to drink salt water.

A local variety of Homo sapiens lives there too, who are endangered in a different sort of way. The authorities want them out because their “presence is compromising the health of the estuary,” according to Palo Alto Weekly. Their poop and trash are considered pollution under the federal Clean Water Act—grounds for eviction. “The welfare of wildlife and the health of Baylands ecosystems is pitted against the very real human needs of people,” the paper opined. Their camps keep getting razed, but like the marshland reeds, they sprout right back.

Different regions of the Valley lend themselves to different expressions of homelessness. In the suburban areas, there are lots of vehicle dwellers because it’s (relatively) easy to find a place to park. In densely developed San Francisco, homelessness is largely centered along sidewalks, pushing the lives of unhoused individuals up close and personal, but keeping camps small and dispersed. Golden Gate Park is a would-be homeless haven, but local authorities have managed to keep camps from proliferating.

In San José, however, local green spaces have been commandeered by the unhoused, with camps that have developed into villages, especially along the Guadalupe River, where the Crash Zone was located, and its tributaries.

San José’s waterways are hideously un-scenic—views are of rubble and trash; the vegetation appears to be in a fight for its life. And although the Guadalupe is called a river, it’s more like a creek that bulges into a torrent on the rare occasion of a multiday rainstorm. Its abused hydrology forms the armature of a shadow city—a new form of urban infrastructure that is unplanned and unwelcome—within a city that does not acknowledge its shadow.

At a community meeting in 2017 to solicit input on a homeless shelter the city wanted to build, a horde of angry residents expressed their discontent over efforts to accommodate the unhoused: “Build a wall,” they chanted.

The Guadalupe River and its camps pierce downtown San José, meandering past the Zoom campus and Adobe’s four-tower headquarters to the Children’s Discovery Museum on Woz Way (as in Apple’s Wozniak, the Apple cofounder), where a community of Latinx campers have chiseled terraced gardens into the riverbank to grow food. People call it the Shelves.

Downstream from the Crash Zone, the Guadalupe flows north along the edge of the airport on its way to the Bay, passing dozens of camps and acres of office parks populated by household names—PayPal, Google, Hewlett-Packard, Roku, Cisco, Intel. One of the biggest camps in this part of town emerged on vacant land owned by Apple, just north of the airport, where the company plans to build yet another campus. Located on Component Drive, it was known as Component Camp.

The Jungle, they said, was “a crime syndicate ruled by gangs, where police do not enter.”

As word spread that displaced Crash Zone residents might soon inundate the place, the company announced they would spend “several million dollars” on a high-end sweep—evicted residents were given vouchers for nine months in a hotel—just weeks before the Crash Zone sweep began.

The Guadalupe’s tributaries tell further stories. Los Gatos Creek leads to the headquarters of eBay and Netflix, as well as Downtown West, a neighborhood being built from the ground up by Google. The city approved a development proposal that included office space for twenty-five thousand folks, but only four thousand units of housing—the sort of job-supply-to-housing-demand ratio that helps put a $3 million sticker on a bungalow.

A report by an economic research firm found that the project’s job-to-housing imbalance would translate to a $765-per month increase for San José renters over a decade—to offset upward pressure on rents, they said more than four times as many units would be needed, a third of them at subsidized rates. The San José Chamber of Commerce declared the report “fundamentally flawed” and dismissed findings like the $765 rent increase. “I don’t think that the stark reality presented in the report is realistic,” a representative told San José Spotlight, “nor something we can expect to happen in the next 8 to 10 years.” In the previous decade, however, median rent in the area had gone up by exactly $763.

Coyote Creek is home to a camp called the Jungle—I never deduced whether this was a reference to hobo jungles or the dense vegetation, or both—on which national media descended in 2014 as it was being swept. It was similar to the Crash Zone in scale, and headlines touting it as the “nation’s largest homeless camp” became a mantra. It was a feast of poverty porn.

“Living in The Jungle means learning to live in fear,” said The Atlantic, quoting a resident who displayed “a machete that he carries up his sleeve at night.” For the UK’s Daily Mail, it was an opportunity to get Dickensian. “Dilapidated, muddy and squalid though it was, it was all they had to call home—a shantytown in the heart of Silicon Valley,” the reporter lamented. “In the last month, one resident tried to strangle another with a cord of wire and another was nearly beaten to death with a hammer.” The Jungle, they said, was “a crime syndicate ruled by gangs, where police do not enter.”

The New York Times was more restrained, striking a valiant tone, with a photo of the mayor himself helping a resident to “wheel his belongings up a muddy embankment.” The local CBS station reported that displaced residents immediately formed a “New Jungle” a half mile away. Before long, they recolonized the original Jungle.

The Crash Zone had grown to the size of the original Jungle, if not larger, by the time I first visited. The fields outside the airport fence technically belong to a city park, but when driving by they appeared like a cross between a junkyard and a refugee camp, in which explosives were periodically detonated. RVs in various states of disrepair butted up to tarp compounds that overflowed with debris, from bottles and cans to appliances and vehicles.

This visual buffet was a mix of freshly prepared, putrefied, and charred—one resident had a tidily landscaped yard with a pair of pink plastic flamingos, while other homesteads were a mix of rotting garbage, blackened grass, melted tarps, and burnt-out vehicles. My eyes flowed over suitcases and furniture and school buses to unexpected items, such as a piano, several boats, and a limousine. The first residents I met cautioned me against wandering into certain sections, where I might be mistaken for an undercover cop—the confetti labyrinth of structures left many a hidden nook where bad things might happen.

One guy had cobbled together a two-story wood cabin; around it were huge piles of wood chips and logs. I wanted to knock but was told the owner wielded an axe and did not like visitors. They called him the Woodchucker.

It was midsummer when I first visited the Crash Zone, height of the dry season in California. Large portions of the landscape were barren earth, and the powder-dry soil coated the skin of its residents. Here and there, people sifted through the loose dirt with their hands; occasionally someone held up a small trinket they’d discovered, inspecting it in the harsh light of the sun.

A woman walked by with a mixing bowl and a toy unicorn, stooping to extract a scrap of blue tarp from the earth, before she continued on. A minimally dressed man pulled clothes from a dumpster and tried them on, not necessarily in the way they were designed to be worn, and quickly took them off again. He spoke incomprehensibly to himself as he did this, tsking and looking annoyed, as though he just couldn’t find the outfit he was looking for. He was thin, barefoot; I wondered how he stayed alive.

I saw a man thrashing his body in anger as he crossed the street. A dreadlocked white guy in a hoodie wandered by with a baseball bat in one hand and a small, sweet-looking dog in the other. The wind picked up; a dust devil spun. A car crawled out of one of the fields with a flat tire, its rim scraping the asphalt as it entered the street. Every five minutes or so, a plane roared overhead like an angry avian dinosaur.

The Crash Zone spilled from its gills, extending beyond the end-of-the-runway fields and into the surrounding cityscape. One end spilled into a series of baseball diamonds, the dugout now housing, the clubhouse a drug den, the bathrooms given over to the sex trade—“People pull through in $100,000 cars trolling for people to blow them in the car,” a resident told me.

On an adjacent street, a man on crutches lived on a bench next to what was once a demonstration garden for drought-tolerant plants, according to a small sign, which had devolved into a garden of rocks and bare earth. The street proceeds across a large bridge where a solitary tent occupied one of the little nooks designed as a place for pedestrians to linger and look out over the Guadalupe. The bike and pedestrian paths that weave through the riparian corridor below provided access to a neighborhood of tents and shacks, a leafy suburb of the Crash Zone known as the Enchanted Forest. Its inhabitants pulled their cars over the curb, using the paths as driveways. Joggers and cyclists and parents pushing strollers paraded through nonetheless.

As San José’s camps have spread, the Guadalupe River parklands have become the frontlines of a local culture war.The tents flowed along the river to the San José Heritage Rose Garden, where thousands of rare and forgotten varieties have been arranged in concentric rings of paths and beds. Some of those varieties disappeared following the Crash Zone’s pandemic-era population explosion, when incidents of arson and “rose rustling”—horticultural theft—were reported by garden volunteers on the site’s Facebook page, the insinuation of who was responsible clearly legible between the lines of the posts. The tents trickled past the roses and collected in clumps along the edges of the Historic Orchard, whose few remaining trees appear murdered and maimed, where they bumped into the six-foot fence that protects the children at the Rotary PlayGarden, a gift to the city from the local Rotary Club. A gate attendant keeps the you-know-who from wandering in to the $6 million playscape.

As San José’s camps have spread, the Guadalupe River parklands have become the frontlines of a local culture war. “The city’s homeless problem is becoming a PR problem,” a CBS anchor said in a 2019 segment. “From their airplane windows, arriving visitors are greeted by a shantytown of tents, blue tarps, and RVs,” they said, describing the trail network that parallels the river as “an eleven-mile stretch of human misery and suffering.”

The campers swim in the animosity that drenches the airwaves and cyberspaces around them. I wondered how my new friends on the street felt when they heard these things. How much does the angst directed toward them undermine their prospects of recovery? I found myself reading the Tripadvisor reviews of Guadalupe River Park, which encompasses much of the trail system. They felt like a beating.

“The once beautiful walking, running and biking trail has been taken over by homeless, garbage, rats,” wrote Robin G. “Really bad,” wrote hob0525. “It was basically . . . a tour of homeless camps. We walked for over an hour thinking it would get better. . . . It did not.”

In a 2019 survey by the Guadalupe River Park Conservancy, 77 percent of respondents did not feel “welcome and safe” in the park. “It’s something that I’ve never seen before, honestly,” Jason Su, the conservancy’s director, told The Mercury News. “This is just on a scale that’s just so, so large.”

It’s as though the city feels it’s been invaded by the unhoused. But turn San José inside out and it’s a giant homeless camp being invaded by a city.

__________________________________

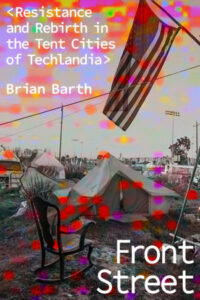

From Front Street: Resistance and Rebirth in the Tent Cities of Techlandia by Brian Barth. Used with the permission of the publisher, Astra Publishing House. Copyright © 2025 by Brian Barth.

Brian Barth

Brian Barth is an award-winning independent journalist with bylines in the New Yorker, National Geographic, Washington Post, The New Republic and Mother Jones, among other publications. He lives between the Bay Area and California's remote Lost Coast region, where he is developing a spiritual refuge—open to seekers, broken souls, and all of humankind—amid a foggy, fern-filled forest. Front Street is his first book.