On the Dark, Wondrous Optimism of Ray Bradbury

Gabrielle Bellot Discovers Worlds Within and Without

Just before his death in 2012—which, by celestial happenstance, was the same day as a rare transit of Venus—a new essay by Ray Bradbury appeared in an issue of The New Yorker devoted to science fiction. It was quick, evanescent, yet the sadness of loss in it lingered in me, a feeling not all readers readily associate with Bradbury, who is often blithely labeled an optimist.

When my grandmother died a few years ago, shortly after I began to transition, I’d thought of Neruda’s “Girl Made of Wood,” which captured a deep-sunken pain I understood; later, I read Bradbury’s essay, which I’d missed when it first appeared, and it rekindled, again, those candles I’d kept in me for her. “I was beginning to perceive the endings of things, like this lovely paper light,” Bradbury wrote of the wistfulness of watching the fire balloons near the end of a 4th of July celebration as a teenager. “I had already lost my grandfather, who went away for good when I was five. I remember him so well: the two of us on the lawn in front of the porch, with twenty relatives for an audience, and the paper balloon held between us for a final moment, filled with warm exhalations, ready to go.” Later, he memorialized his grandfather in a short story, “The Fire Balloons.” “One of the priests was like my grandpa,” he reveals, “whom I put on Mars to see the lovely balloons again, but this time they were Martians, all fired and bright, adrift above a dead sea.” This pretty, poignant juxtaposition of “fired and bright” with “a dead sea” illumes something in Bradbury’s writing broadly: a persistent, yet tainted and limited, positivity, which becomes murkier, less clearly positive, the deeper we plumb.

At a glance, Bradbury can seem excessively cheery, his fiction bursting with a simple positive bombast that stretches, at times, into naiveté and clichés about good and evil, gender roles, religion, and science. When I recently reread Something Wicked This Way Comes, I was struck by how, in one breath, Bradbury could go from perspicacious, precise imagery to ham-fisted, trite moralizing. And the great chronicler of Martians himself sometimes emphasized this saccharine self-portrait. “I believe we’ll be immortal, seed the stars and live forever in the flesh of children,” he declared in 1975 with the death-defying assurance of a transhumanist. His “job as a writer,” he continued, was “to show man his basic goodness… I reject the doomsayers!” Yet there is more than a little dusk beneath this sprightly veneer.

The visions of the future in some of his best-known texts, while sanguine, are quietly bloody in another sense. Ambrose Bierce—who appears as a character in The Illustrated Man—described pessimism in his delightfully perverse Devil’s Dictionary as a natural response to “the disheartening prevalence of the optimist with his scarecrow hope and his unsightly smile”; Bradbury was a rosy smiler, like the charming scarecrow in Howl’s Moving Castle, but no mere romantic idealist. Instead, he was a darker optimist, an optimist of the evening. We all have, need to have, a piece of night in us. Bradbury’s pictures of his era and his prophecies for the 21st century were as hopeful as they were quietly horrifying, and, unexpectedly, they helped me find a language for loss.

In what I consider Bradbury’s masterwork, The Martian Chronicles (1950), Earth, by the dawn of the 21st century, is expecting atomic warfare. Early on, an unnamed character is convinced that “thousands of others like him” wish to escape “a big atomic war on Earth in about two years” on rockets to Mars, the latter of which Bradbury’s novel suggests we might casually be using for interplanetary relocation by 1999. (Though Chronicles is more fantasy than firm prognostication, it was not uncommon to imagine the 21st century as one of easy space travel; in his essay “To Be Transported,” Bradbury also dreams of a 2001 in which all the world unites “before our first manned ship to Mars.”) Throughout Chronicles, Bradbury repeatedly invokes this fear of nuclear devastation. Human life on Earth goes on, but this subtle refrain foreshadows our home planet becoming less hospitable than Mars, that those unable to escape on rockets will be be exiled on an Earth turned xeric flickering desert, if they survive at all. Later, nuclear war fatally consumes the globe. “The blood-dimmed tides,” Yeats might have put it.

Still, this atomic destruction rarely comes to the forefront in Chronicles, and, consequently, it’s easy to focus more on Mars than our own planet’s loss. Yet a soon-to-be ravaged planet was Bradbury’s quiet image of 21st-century Earth. After the Second World War, the idea that great swathes, if not all, of humanity might be extirpated by nuclear bombs was commonplace; so suddenly unexceptional was this anxiety that Bradbury felt content to thread it into the casual background of his story rather than spending time to convince readers such doomsday fears were justified. (It’s reminiscent, too, of Kennedy’s famous 1963 declaration that “[e]very man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness.”) Beyond atomic unease, there is, unsurprisingly, racial discord; the American South in the early 21st century is still full of crass, quotidian anti-black racism, and Bradbury shows black Americans leaving, in a sussultatory scene of exodus, for a Mars-bound rocket. (In “The Other Foot” in The Illustrated Man, they’ve built an all-black society on Mars, interrupted by the arrival of a white man from a bomb-destroyed Earth).

Yet the Red Planet is no halcyon landscape. Instead, it becomes a prism for colonialist catastrophe. Smallpox, a disease the humans unwittingly bring with them, quietly massacres thousands of native Martians. Other Martian life is deliberately extinguished as Earthlings continue trying to “civilize a beautifully dead planet”—a telling choice of words. The corpses and skeletons of the indigenous Martians lie in abandoned towns that, once filled with festivity, are now sepulchrally silent; macabrely, children play with the Martians’ bones and ashes, and, later, firefighters burn away the dead, as if to erase a terrible past. The terrestrial travelers attempt to recreate Earth on Mars, imposing their will (and conservative, banausic gender stereotypes, unfortunately common in Bradbury) upon the “new” world.

To read this as a child of European colonialism is to see obvious, bloody parallels. Presaging Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury describes a mass purge of art and ideological dissent in a terrible 1975 “Great Fire”; the novel’s fascistic morality police (“good clean people”), who later travel to Mars to “cleanse” it, even seek, puritanically, to ban and destroy all things “dark”: Halloween, bats, horror literature. No wonder there’s a shadow to Bradbury’s optimism. Fascism, Bradbury knew, would be alive and well in our century.

Mars may offer solace from a moribund Earth—but it also proffers fresh land for us to destroy and, in turn, be destroyed on. Bradbury’s masterwork of humans yearning for new lives is littered, page after page, with death, with the banality of evil.

An embittered optimism, indeed, where we lose even as we gain.

*

I lost my grandmother a sea away. She had died in my former home, Dominica. She never knew me as Gabrielle, never had a chance to meet her newest granddaughter before her heart failed. Do not return home for the funeral, my parents told me, lest my presence conjure up shame, ridicule, danger, Lady Death with her blue curls. Someone openly queer didn’t belong.

When I reread Something Wicked This Way Comes, I began to think of my grandmother, again. Bradbury conjures up a merry-go-round that can change our age; if it revolves forward, we grow a year older with each circle we ride, and if it spins widdershins, we get younger. I thought of what I would do if, suddenly, she sat across from me again, magically given one more year to live. She would not have recognized me, I realized. She might have even thought I was one of my female cousins. I would have had to repeat my name because she had grown hard of hearing, and she would repeat it, too, because after so many years her voice had thickened into a slur that my mother said was the remnants of her deep Curacao accent.

But I loved hearing her tell stories about the 13 girls and six boys she had given birth to in Dominica, even if sometimes I missed the words she was trying to convey. I had always gone to see her as a kid and on my returns to Dominica from university in America; sometimes, she would forget I or any of her other grandchildren had visited her at all, her memories dimming like an old lighthouse beam, but her face would brighten every time she saw us because she was lonely and even the scraps of routine conversation we often gave her seemed to make her happier, seemed to stir up the stagnant time inside her. Big and little things made her proud: a good grade, going to college abroad, passing exams. She seemed like a second mum in that way. I thought her a fixture, always sitting on her chair in the kitchen of my aunt’s house facing the glass-wood door and its stone steps.

I had known her for so long that I naively never really believed she would die, could die, even as my mum often talked, in hushed tones, about her failing health. I wished, stupidly, the carousel was real, and I could see her one last time, and for the first time as the woman I am. When I came out, my parents told me not to return to my home; later, my mum texted me, with a reproachful sadness, Granny asks for you. No one would tell her why I had stopped coming to say hi to her from America; it was too shameful, too wrong.

And then I wondered if my parents were right. Maybe the sight of me would have upset her. Caused her heart to fail faster from confusion, frustration. Perhaps she left this world in a peace she couldn’t have had if she had seen me as something so distant from the child she’d known for two decades. I had become a strange, delphic language. Perhaps the sad truth is that not everyone can say all names. I still don’t know.

In Bradbury’s novel, evil is vanquished by good, yet the protagonists know the darkness will soon return. An optimistic moral tale suddenly becomes a bit scarier, a bit wickeder.

Sometimes, we just have to learn to accept the dark, to accept night has come, no matter how someone we love raged against it.

But I kept thinking of that carousel, wishing, so much, I could hear my name for the first and last time in her voice.

*

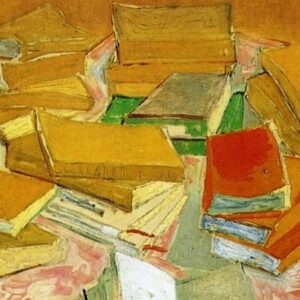

The story of Bradbury’s that meant the most to me was “All Summer in a Day.” It hurt in a way I understood. The story’s setting is Venus, where Bradbury says the sun only shines briefly once every seven years; between these years, rain falls constantly. Venusian schoolchildren are excited to see the sun, but one oft-bullied girl, Margot, will be denied this rare vista. The kids hate Margot, treating her as the Other; “she was different and they knew her difference and kept away,” Bradbury writes. Just as the sun is about to appear, bullies stuff Margot in a closet and forget about her while they gallivant under the marvelous light. Near the end, they suddenly remember her; chillingly and painfully, “[b]ehind the closet door was only silence.” The story ends on this disquieting note, with Margot slowly released from her imprisonment.

I knew that closet so well, its scent, the places where the wood had chipped. I knew it as a queer girl in an anti-queer country, knew it when I put myself inside it, over and over, lest too much light reveal who and what I truly was. I knew the way my parents had wanted me to stay in that cramped closet forever, not speaking, not moving. I knew I would shut myself back into it when my grandmother died because I knew, already, the ridicule and danger to come if I stepped out and returned home for her funeral. Then I felt furious and ashamed because I so wanted to see her again, even in the coffin, even as a mysterious silent girl in the church’s back pews. Wanted, somehow, to make her proud one final time.

Silent. Closet. I think of how much such little words hold. How some words unfurl, and others tighten. How Margot’s closet is a death-door.

In the end, Bradbury and Margot were alike. Both kids’ worlds—for Bradbury was always a child at heart—ended with that echoing silence on a day so rare that we would have expected, instead, to hear Bradbury and Margot cheer.

*

Bradbury, who never used a computer or drove a car (and believed automobiles more dangerous than war), could be described by a little-known word in English derived from Portuguese, nefelibata: one who walks in the clouds. For better or for worse, we don’t as yet live in the future he imagined, and his predictions and screeds can feel quaint, if not ingenuous or tone-deaf, today. Yet at its best, his work is so imaginative that I feel able to drift off, up, for a bit, and dream. Sometimes, those dreams of carousels and closets hurt. But other times, they heal. An adjuvant art.

In those dreams, I can walk on the clouds, for a little, and imagine finally telling one of my loved ones goodbye.

Gabrielle Bellot

Gabrielle Bellot is a staff writer for Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, The Paris Review Daily, The Cut, Tin House, The Guardian, Guernica, The Normal School, The Poetry Foundation, Lambda Literary, and many other places. She is working on her first collection of essays and a novel.