On the Dangers of Romanticizing Gentrification in Your Novel

Tobias Carroll Examines a Perennial Concern of New York City Lit

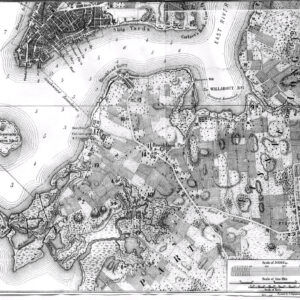

I once wrote a failed novel about a successful city. Well, that might be simplifying things a bit. About a decade ago, I wrote a novel set in part in mid-aughts Greenpoint, writing about the blocks and regions I was familiar with. There was something appealing about capturing the mood of a place; there was also something appealing about trying to create a record of a real place in fiction. (Part of the book’s structure involved its protagonist moving to increasingly stylized environments, the realism of the first part giving way to something more surreal by the last.) And there was also the understandable urge to act as a kind of translator between the landscape outside my window and words on a page.

What was at the time a neighborhood, and a city, in flux is now something new—Bloomberg-era growth giving way to the recriminations and housing dilemmas of the de Blasio years. In a recent interview with Carl Swanson in New York, onetime deputy mayor Dan Doctoroff was candid about some of the flaws of the administration he was a part of. “The main thing Doctoroff admits the administration didn’t quite get right was figuring out how to keep New York from becoming too expensive for many of the people who already lived in it,” Swanson writes—which is perhaps the urban planning version of “Other than that, how was the play, Mrs. Lincoln?”

There’s an inherent romanticism that can come up when writing about cities, whether exploring their history in works of nonfiction or using real streets, buildings, and events in the context of a novel. Cities have their own mythology, and that mythology can and does draw people to live there. Sometimes that mythology can be of the variety that summons up creative or personal triumphs. Other strains of it hearken back to a bleaker stretch of history: I can remember browsing the shelves at St. Marks Books in the early 2000s and seeing prominently displayed copies of Herbert Ashbury’s The Gangs of New York. More recently, Luc Sante’s Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York has taken a place as a favorite of many a local bookstore here. These are not books that make the New York of centuries past seem appealing; still, given the skill of their authors, they do turn the dangers of history into something that adds to a city’s legend—a powerful thing in and of itself.

Early on in his recent book Vanishing New York: How a Great City Lost Its Soul, Jeremiah Moss chronicles his own arrival in the New York of a bygone era. “I came to New York because I needed the city, and New York is for people who need cities, for those who cannot function outside of one,” he writes. For the last few years, Moss has been documenting institutions within the city that have been shuttered or relocated due to economic pressures; more recently, he’s shifted that outrage into a more focused activism, exploring ways in which cities can preserve the businesses that give neighborhoods their identity.

Moss’s book reads like an expansion of this: he documents certain spaces that are now lost, he rages at how the city’s government—particularly during Michael Bloomberg’s time in office—prioritized attracting new businesses and wealthy individuals to the city rather than improving the lives of those that already existed. But also contained within the narrative is Moss’s own personal arc, which includes nods to his time as a poet as well as his time as a social worker. (Alternately, if you sought someone to track the parallel economic and creative shifts within the city, Moss might well be the ideal person for the job.)

In Vanishing New York, Moss describes the way the rougher aspects of a city’s history can be commodified, citing the uniforms of employees of a luxury hotel in the East Village as one example.

“The hotel’s doormen wear red waistcoats and black bowler hats, echoing the hotel’s logo of a Bowery Boy, a member of the late-19th-century, nativist gangs who went around Five Points beating Catholics and other immigrants.”

Moss recognizes the complexity of the issue he’s writing about here: that criticizing anyone who seeks their fortune in New York, as he did, could come off as hypocritical. He pulls off a deft rhetorical move, ultimately finding the middle ground between calling for an entirely static city and embracing any and all change.

And throughout the book, Moss cites a kind of literary canon of writing about New York City, including Pete Hamill, James Baldwin, Rebecca Solnit, Robert Caro, and Kate Millett. He also quotes Cari Luna, whose 2013 novel The Revolution of Every Day dealt with one specific example of the rapacious gentrification that Moss decries—specifically, the destruction of squats on the Lower East Side. Here, too, is the place in which words on a page can evoke a city’s skyline or the sidewalk below your feet. Here, too, is the paradox that can exist on the periphery of city life.

There’s a different sort of paradox to be found in Victor P. Corona’s Night Class: A Downtown Memoir. Corona’s examination of cultures and subcultures in New York is more focused: specifically, he’s writing about clubgoers and aesthetics, and also about his own immersion in this world from an initially academic perspective. He also writes about the cultural magnetism of New York City—and of how the downtown club scene’s aesthetics made it a beacon to many across the country.

Corona also traces the highs and lows of the scene, and how New York’s economic fortunes affected it: by the final quarter of the book, he’s described the way that one club owner has repurposed elements from shuttered spaces into new ventures (“like organs extracted from the dying to sustain the living”) and the role of pop culture—including the television shows Gossip Girl and Sex and the City—from turning an underground scene into something much more widely accessible.

*

Reading Moss and Corona offers a balance of history and theory, of societal policies and memorable figures from the city’s recent history. But how does that translate into fiction? How do these personalities ultimately veer into characters in a novel? How does the tension around post-Giuliani New York become embodied in a plot? And do these narratives have the potential to themselves become magnetic, alluring a new generation of potential urbanites to cross the Hudson or East Rivers and make their way into the five boroughs?

This can show up in innumerable ways. In Francesco Pacifico’s Class—a novel that critic Christian Lorentzen called “the novel to take on the Williamsburg of high-rises and clapboard houses, just-finished condominiums, and Bedford Avenue boutiques—the hipster dreamland”—there are several references to cultural depictions of New York City that have attracted the wealthy Italian expatriates that populate this novel. “The cab driver is 80s Jarmusch, independent film, the world as it was before the Lorenzos of the world found out enough about it to co-opt it.” Pacifico also works in a number of real-life artists to the book’s plot, including the great avant-rock band Oneida and the DIY venue Secret Project Robot. It’s not hard to see someone reading this novel and being drawn in to the version of the city, sometimes realistic and sometimes stylized, that appears within its pages.

Brian Platzer’s novel Bed-Stuy is Burning is an interesting case in point. It’s both a novel that grapples with some of the biggest issues of today, including police violence and gentrification—it centers around an affluent white couple who have recently moved to the Brooklyn neighborhood that gives the novel its title. Before the novel opens, police have shot and killed a black teenager, creating outrage in the surrounding community. Given the title, it’s not really a spoiler to say that things escalate rapidly, heightened even further by the presence of a Chekhovian gun in the possession of one of the supporting characters.

Platzer’s novel is decidedly contemporary in its scope; at one point, former NYPD Commissioner William Bratton shows up in the narrative. But it’s also a work that hearkens back to notable New York-centric literary works of years past. Specifically, there are moments in it that hearken back to both Anna Deveare Smith’s Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn and Other Identities and Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. It’s a bold aesthetic decision, but one that seems eminently logical: if you are telling a story that seeks to encompass a variety of perspectives across lines of race, gender, and class—as Platzer is here—those are certainly two models to follow. But the two are also working at different ends: Smith’s work is inherently empathic, striving to find the shared qualities between people on opposite sides of a heated debate. Wolfe’s penchant for satire, meanwhile, assumes a worldview wherein even the most virtuous people have feet of clay, and nearly everyone’s flaws offer the potential for ruination.

The way that literary New York begets real New York begets literary New York is neatly summed up in Jarett Kobek’s novel The Future Won’t Be Long. It encompasses the occasionally strained friendship between Baby, a struggling writer, and Adeline, a student. They meet in 1986; the novel traces their own shifting fortunes—as well that of the city around them—over the course of the next decade. Though the two have an immediately strong bond, they also work in different media—Adeline finds her home in the indie comics scene, while Baby’s literary career begins with cerebral science fiction and veers into the more overtly literary. Adeline comes from an affluent background, while Baby’s is more humble—and the lenses through which this shapes each of their experience in the city is telling.

From an early point in the narrative, it becomes clear that the New York in which Baby and Adeline dwell is one shaped by its literature. Baby encounters Thomas M. Disch, finds a copy of his Camp Concentration at The Strand, and is floored; Adeline slowly becomes a vital part of the comics world; Grant Morrison is one of a number of real-life figures who has a cameo. There are enough signifiers of 1980s New York culture to feel overwhelming at times: references to Slaves of New York and The Rules of Attraction; characters venturing to Spider-Man’s live-action wedding at Shea Stadium.

And as bizarre as that event was—and, to be clear, that was an absolutely real event—it serves as a spot-on touchstone for the novel as a whole. This is a literary novel about New York that is fully suffused with other literary novels about New York and whose characters have basically internalized the accumulated mythology of decades’ worth of literary novels about New York. As if to make this point even more clear, The Great Gatsby’s famous line about repeating the past (and its rejoinder) is itself repeated a few times over the course of the narrative—half homage to Fitzgerald’s themes and half knowing remix, vocalized by characters who are conscious of the reference but embrace its impossibility regardless. Sure, Gatbsy couldn’t repeat the past—but hey, I might be the one who can pull it off.

It’s a paradox, then: even creative works that might be designed as cautionary tales about the pitfalls that can befall those seeking a more fulfilling life in New York City can prompt people to seek a more fulfilling life in New York City. And the lines between fictional and nonfictional narratives can blur: one can imagine the frustrated artists of Class or Bed-Stuy is Burning nodding along with the tales of shuttered spaces in Vanishing New York, and some of the real-life figures in Night Class show up in lightly fictionalized form in The Future Won’t Be Long. One person’s real-life story of urban unrest is another’s acclaimed novel waiting to happen. A cumulative look at these books shows the way that a city can slip into fiction, and the way that fictions can reshape a city.

Tobias Carroll

Tobias Carroll is a writer and essayist, and the managing editor of Vol. 1 Brooklyn. He is the author of three books: Political Sign (Bloomsbury), part of the Object Lessons series; the story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird).