On the Dangers of Nostalgia: A 1990s Reading List

Samuel R. Delany, Alexander Chee, Myriam Gurba, and More

There’s such an intense nostalgia for the 1990s right now—in popular culture, in music, in fashion, even in activism. But nostalgia can be dangerous because it replaces the complexity and nuance of lived experience with a consumer-friendly product for mass consumption. When I was coming of age in the early 90s, I remember older queens looking at my bell-bottoms and saying girl, did you take those from my closet? I wasn’t wearing bell-bottoms because I wanted to invoke the 70s, I just wore them because they were the wildest pants at the thrift stores, but nostalgia and cultural amnesia may be two sides of the same coin. Now that Nirvana t-shirts and septum piercings, oversized plaid shirts and designer leggings are supposed to represent the 90s, how can we summon a deeper engagement? The opposite of nostalgia is truth. Here are five books that may offer just that.

Sara Jaffe, Dryland

Dryland, Sara Jaffe’s first novel, is a book driven by pent-up emotion. The narrator is a high school sophomore trying her best to mimic the calculated nonchalance of teenage sophistication, and yet of course there’s that churning beneath the surface. Set in 1993, the book starts as a queer coming-of-age tale that opens up through music, carefully interspersed through the text, but it’s not music cleverly placed to offer a hollow signifier of a specific time, it’s music that opens up into feeling. When Jaffe writes, “The song made me want to have lost something, so that I could want it back,” the narrative breaks open. It’s these moments that give the book an undercurrent of longing for belonging, and gesture toward the possibilities for communal understanding in the age of AIDS.

Myriam Gurba, MEAN

MEAN is a hybrid memoir about rape and sexual violence, structural and internalized oppression, anti-Mexican racism, and, yes, growing up in the 80s and 90s. While MEAN burst onto the scene in the midst of our current national conversation about sexual violence, much of the violence in the book takes place decidedly in the 1990s, when Myriam Gurba was raped by a stranger in a Southern California park. Her writing is caustic and scathing, and eloquently targeted. She writes, “Guilt is a ghost. Guilt interrupts narratives. Ghosts have no etiquette. What do they need it for?” In this book that speaks so much to today’s conversation, and yet from the perspective of traumatic and traumatizing events decades ago, there are no easy answers, no pat conclusions, and no simplistic resolution. One way to write about the past is to write about how it still haunts us today.

Rebecca Brown, The Gifts of the Body

One of the best ways to read about the 1990s without the corruption of a nostalgic lens is to go back to books written in the 90s. Rebecca Brown’s The Gifts of the Body, which came out in 1995, is a wrenchingly direct novel told from the point of view of a home care worker for people dying of AIDS—one after the other, there is no hope except for the hope of care. When I first read it, I read it as nonfiction—that’s how sharp and intimate the descriptions are. The innocence and wisdom, the desperation and shock of the dying. The pain of a generation. In my new novel, Sketchtasy, the narrator, a 21-year-old queen coming of age in 1995, reads The Gifts of the Body in order to access her own emotions about what’s going on in the world around her. This is the kind of kinship a great book can provide.

Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue

Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, published as the 1990s came to a close, is Samuel Delany’s ode to, and elegy for, Times Square. Rather than an invocation of the 90s, it’s a cautionary tale about the gentrification of Times Square, as corporate developers and corrupt city officials sealed the deal on the whitewashing and blandification of the neighborhood, with its ensuing waves of displacement. Delany’s prose is both clinical and intimate, as he describes, from the point of view of both participant and observer, the cross-class and cross-cultural possibilities that Times Square’s porn theaters and sex crossroads offered. Far from an idyllic time, the late-90s mark the transition into hyper-gentrification, as formerly vibrant neighborhoods were transformed into hollowed-out destinations for elite consumption at any cost—most cities with access to resources have followed the same tragic path. Now the mentality in our cities is often barely distinguishable from that in the gated suburbs city-dwellers once fled, and Times Square Red, Times Square Blue may be more relevant than ever.

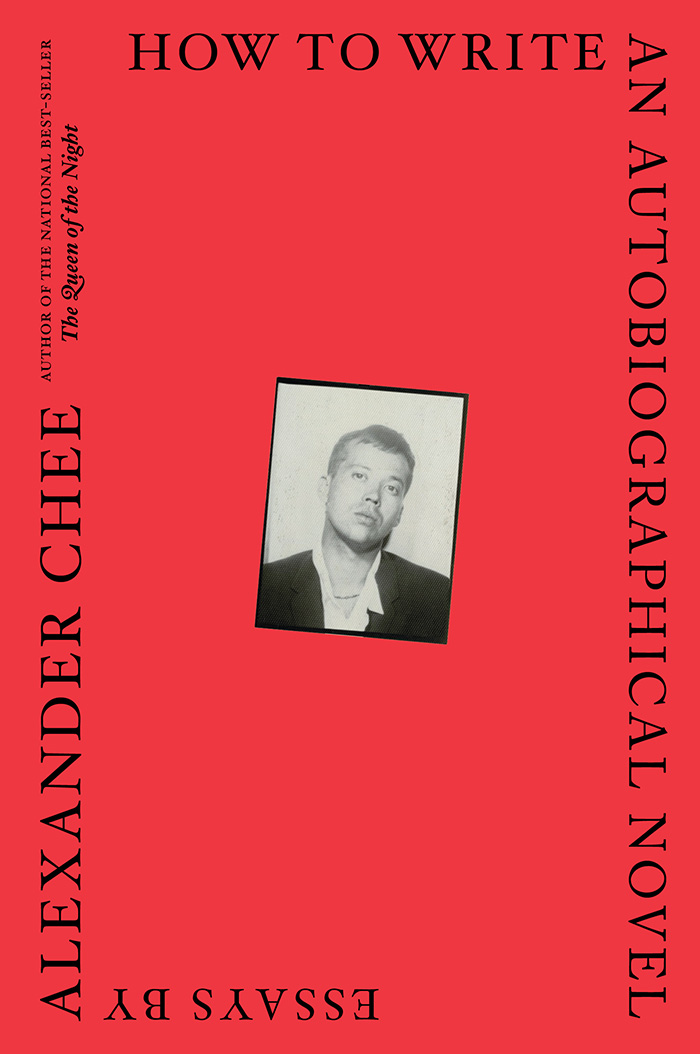

Alexander Chee, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel

How to Write an Autobiographical Novel is a meticulously crafted collection of essays about exile and home, the impossible dream and its loss; it’s a dream despite the violence of this country, both intimate and structural, and a history of queer and queenly dreaming in one particular life. The essays in this book span four decades, but I think the essays about the 1990s—or, more specifically, the dawn of the 90s, are stunning in their range and capacity to convey layers of intimacy, loss, dreaming, and breadth of imagination. When Chee writes, “those of us in my generation who lived in San Francisco had to overcome the false impression that no one like us had ever existed before, because the ones who might have greeted us when we arrived were already dead,” he offers the clarity of hindsight while conjuring a past coursing through the present. As someone of this same generation, who moved to San Francisco a year after Chee left, I can barely keep myself from crying. Maybe this is what it means to truly remember the 90s.