On the Countercultural Influence of Peanuts

David Ulin Considers Linus, Boy Philosopher

Here’s where it begins for me: a four-panel strip, Lucy and Linus, simplest narrative in the universe. As the sequence starts, we see Lucy skipping rope and, like an older sister, giving Linus a hard time. “You a doctor! Ha! That’s a big laugh!” she mocks. “You could never be a doctor! You know why?” Before he can respond, she turns away, as if to say she knows him better than he knows himself. “Because you don’t love mankind, that’s why!” she answers, seeking (as usual) the final word. Linus, however, he defies her, standing alone in the last frame, shouting his rejoinder out into the distance: “I love mankind . . . it’s people I can’t stand!!”

When I say begins for me, I mean it figuratively; that strip ran on November 12, 1959, nearly two years before I was born. What I’m describing, rather, is a sensibility, a way of looking at, or engaging with, the world. I still remember the moment I stumbled across that set of images, entirely by accident—which is as it should be. It was the middle of June 1968, and I was in the finished basement of a cousin’s house in suburban Michigan. I still remember encountering the punchline with the flash of recognition someone else might call epiphany. Me, I don’t believe in epiphanies, or perhaps it is more accurate to say that they seem too convenient, that life (my life, at any rate) rarely unfurls itself in such a way. Nonetheless, I can tell you that even at the age of six—I would turn seven later in the summer—I knew I shared some of Linus’s . . . misanthropy is not quite the right word here, but distance, self-containment, solitude, that this was how I understood who I was.

What were we doing in Michigan? My family—my parents, my two-year-old brother, and myself—were driving from Southern California, where for the last year my father had been on a fellowship, to Connecticut, where we would spend the summer at my grandparents’ house. The cousin in question was not mine, not really, nor my mother’s, but my grandmother’s, which left us twice removed. He and his wife had older children, one a son in college, whom I admired for his long hair and his politics. (We were a political family, had left California a few weeks before we’d meant to, after one of my father’s colleagues told my mother he did not regret the death of Bobby Kennedy, who had just been gunned down in Los Angeles, in a kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel.)

Do we ever change? I don’t think so, no, not really. Linus rendered this notion three-dimensional to me.The Michigan house was modern, with sliding wooden doors that, I chose to imagine, worked like those on the starship Enterprise. I was a huge Star Trek fan; my father and I would sit on the couch in the living room and watch it together every week. In Michigan, I spent a good amount of time sliding those doors open and shut as if they were automatic while making a whooshing sound between pursed lips. The college-age son, he observed this; he also observed that I enjoyed reading. On the second or third day of our visit, while the adults were upstairs doing who-knows-what, he found me in the basement and introduced me to what I would later come to think of as his secret stash.

“Do you like Charlie Brown?” he asked, and when I told him yes, he gestured at a shelf of mass-market paperbacks, 20 or so of them in a variety of primary colors, collections of Peanuts comics going back close to 20 years. I was familiar with the television specials, loved the theme song by Vince Guaraldi, the lilting piano riff I could hum from memory. (I am humming it now as I write this: da da da da da dada da da.) But these books—they were a revelation, because I had never seen the strip. My parents didn’t read the funnies, believed them to be a form of lowbrow entertainment; at least, this was how my mother put it a decade later when she announced she was throwing out my comic books. In Southern California, they did not subscribe to the local Times, which featured a comics pages, but to that other, grayer Times out of New York.

Over the next three or four days, until we left Michigan for Columbus, Ohio, where my mother’s brother was serving a two-year stint as a doctor at Lockbourne Air Force Base, I sat in that basement and tore through every one of those books. If they didn’t include all the Peanuts strips then in existence, they must have come pretty close. What I remember most, though, is that punch line: “I love mankind . . . it’s people I can’t stand!!” So much so that when I looked it up online to make sure I was quoting it correctly, it was exactly, down to the punctuation, as I recalled.

This interests me because I would not describe myself as a Peanuts obsessive, nor as anything more than a casual fan. Yes, I had a Snoopy throw pillow on my bed in grade school (as a teenager, I used to exhale bong hits into it, so my room wouldn’t reek of weed), but hey, it was the early 1970s, and so did everyone. Yes, I knew the characters: Lucy, Charlie Brown, and Linus; Schroeder, Violet, and Woodstock. In college, after I met the woman I would later marry (she was a redhead), I would jokingly call her, on occasion, “the Little Red-Haired girl.” Such signifiers, however, are now so common that they function as a kind of cultural wallpaper. We take them for granted, we do not see them; their power to surprise or even stir us has been, on the most basic terms, stripped away. “He was the king and he showed us how to do it,” Bloom County creator Berkeley Breathed said to me of Charles M. Schulz (one of his primary inspirations) during a 2003 interview. “Why didn’t he stop and leave us with those memories, rather than, in the last ten years of his life, drawing Woodstock falling off the doghouse over and over?” At the same time, does it really matter?

Breathed regarded Schulz as a figure on the level of Elvis, not the burnt-out one in the white jumpsuit, but the hungry one who made those Sun recordings, which literally—and in every way that counts—reframed the world. “Don’t worry about it,” Schulz’s widow Jean told Breathed. “You have to understand that Sparky lived to do this. He would have died if he had stopped.” And in fact, that’s just what happened. He died on February 12, 2000, less than two months after announcing his retirement, and the day before the publication of the last new Peanuts strip.

What does it mean to speak for yourself? What does it mean to feel that pull? I began to ask these questions when I first encountered Linus’s fervent charge.Still, Linus. For me, he offered something of a gateway—less a weird kid than one who encouraged me to be . . . myself. I liked that he stood apart, clinging to his security blanket even when Snoopy tried to grab it away. I liked his faith, and his lack of faith: that tension between mankind and people again. “I was the victim of a false doctrine,” he declares after being disappointed by the Great Pumpkin, although the following year, he is (how could he not be?) in the pumpkin patch once more. “Why worry about the future when the present is more than most of us can handle!” he reflects, articulating a belief system that allows him to occupy a middle territory between despair and hope. He is the boy philosopher, wise beyond his years.

“Here’s something to think about,” he avers in a May 1981 strip. “Life is like a ten-speed bicycle . . . / Most of us have gears that we never use!” Potential, in other words, the insistence that we are always growing, or could be—ironic since his physical persona, his face and hair and body, never changed. Perhaps this is why my favorite image of him is not from Schulz, but from a Mad magazine satire in which the Peanuts crew is portrayed in their teens. Linus has become a beatnik, scruffy beard but still clutching that blanket, as if all the ages, childhood through adolescence, had come together in one body, which is, of course, the way it has to be. Think of me as a high schooler, breathing smoke into that Snoopy pillow. Do we ever change? I don’t think so, no, not really. Linus rendered this notion three-dimensional to me.

In that sense, Linus was my earliest countercultural hero, the first to indicate a certain set of possibilities. And not just him, but Peanuts in general, although he was (and remains) the avatar of this idea. “To the countercultural mind,” Jonathan Franzen wrote, “the strip’s square panels were the only square thing about it. A begoggled beagle piloting a doghouse and getting shot down by the Red Baron had the same antic valence as Yossarian paddling a dinghy to Sweden. Wouldn’t the country be better off listening to Linus Van Pelt than to Robert McNamara? This was the era of flower children, not flower adults.” Partly, this is a function of the moment: Ron McKernan, the Grateful Dead’s notably unkempt harmonica and organ player, took his stage name from the character of Pig-Pen. At the same time, the strip represented a safe place in a chaotic world. Schulz’s Pig-Pen is filthy, yes, but McKernan was a severe alcoholic who was only 27 when he died of a gastrointestinal hemorrhage. In reality, potential, possibility, don’t always pan out; they can take us places we don’t want to go. Art can do that also, but it doesn’t have to—or better, when it does, it does so for a reason, even (or especially) when there are no epiphanies. As I’ve suggested, Peanuts led me to Mad, which led me to Wacky Packs and Monty Python, which revealed to me the conditionality of . . . everything. Adult life looked ridiculous because it was ridiculous: “All those egos,” to borrow a line from J. D. Salinger, “running around feeling terribly charitable and warm.”

The dynamic is one in which Peanuts regularly trafficked; think of Lucy, who is all ego—or, more fundamentally, all id. But somehow the strip managed to be gentle also, to clear a space, within its fractured moment (and maybe ours, as well) for everyone. That may explain my offhand relation to the strip—I was looking for something more provocative, with rougher textures—even as I came to know it well.

Comics, Art Spiegelman insists, move us in just such a fashion: with their familiarity, which is enhanced by our repeated interactions over days and years. “Comics aren’t made to be read,” he told me once, “they’re made to be re-read. If you only read them once, they weren’t worth bothering with.” On the one hand, Spiegelman is referring to accessibility; comics are the original disposable art. And yet, this doesn’t mean that they are lowbrow, but the opposite. What they offer is a shared vernacular. What they offer is a language we all understand. The four-panel arc is as natural to us now as the rhythm of a Bible verse must have been to an earlier generation: anticipation, set-up, and release. This is why the parodies are so effective, because we are all in on the joke.

Take “Good ol’ Gregor Brown,” in which R. Sikoryak conflates Schulz with Kafka in a brilliant act of visual ventriloquism. Nine four-panel strips retell the story of The Metamorphosis, with Charlie Brown as Gregor and Linus as the office manager. Nowhere does an adult appear; you can almost imagine Gregor’s parents, not unlike the teachers in a Peanuts television special, making wah-wah-wah sounds as they fret beyond the edges of the frame. This, too, was part of Schulz’s achievement, to recognize that childhood was an existential landscape, in which, say, the struggle to hold onto a security blanket or believe in the Great Pumpkin is the struggle to keep hope alive: as important and defining, as anything in the adult world.

In the end, what makes this meaningful is decency, which is also what Linus is about. It is, after all, people he dismisses in favor of humanity, and not the other way around. The same, I would submit here, was also true of that long-ago college student, my grandmother’s cousin’s son. He saw a six-year-old—bored, a little lonely—and reached out with a whisper of consolation, a glimpse of something bigger, something else. He didn’t have to do it; I don’t know that I would have, nor that I would have noticed, even, much about that little boy at all. Decency again, or empathy, a sense that we are all in it together, joined in the collective known as humankind. The last time he and I saw one another, a decade ago at my parents’ 50th anniversary celebration, I recalled his kindness, as I do whenever our paths cross. I have never said a word about it, though; I’m not sure he would remember, and it doesn’t matter anyway. What is resonant to one of us is often (usually?) forgotten by another; it is the subjectivity upon which identity depends. Who’s to say what his experience was in that basement? Who’s to say what he thought, or what he imagined he was doing, or what, if anything, about it was important to him?

No, what lingers is the comic. What lingers is the voice. What lingers is Linus, alone but also with his sister, as I was alone with, well, everyone. “I love mankind … it’s people I can’t stand!!” The distinction he is making is a subtle one, but it is also unmistakable. It represents the voice of the iconoclast, the individual, eager, desperate even, to be a part of it (whatever it is) at the same time as he wants to stand apart. Do I need to say that I still feel like this, half a century after discovering those words? Indeed, I feel the sentiment as strongly now—perhaps more than that—as I ever have. We live in a world Schulz couldn’t have imagined, with its hyperlinks and networks, social media and connectivity. We live in a world where a sense of shared humanity seems the most impossible of conceits.

It is a world that the Peanuts kids, they wouldn’t recognize, although if Linus has anything to tell us, it is that mankind, humanity, what exists at the heart of us, it remains the same. What does it mean to speak for yourself? What does it mean to feel that pull? I began to ask and (yes) to comprehend these questions on the afternoon, in that basement in suburban Michigan, I first encountered Linus’s fervent charge.

———————————————

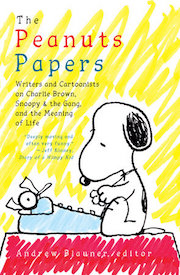

From The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life edited by Andrew Blauner. Copyright © 2019 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.. All rights reserved.

From The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life edited by Andrew Blauner. Copyright © 2019 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.. All rights reserved.