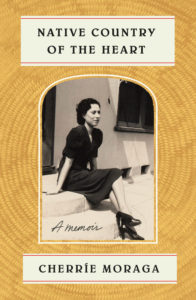

Aging in America: Cherríe Moraga on Her Mother’s Struggles

Growing Up in a Mexican-American Family and Revering One's Elders

There were times in which I did not know whether my mother was truly demented or just Mexican in a white world. I knew she was ill, that she suffered enormously; but I often doubted if the medicine for that illness (psychotropic drugs and the culture of care for elders in this country) was adequately designed for the woman whose emotional memory defied the limits and logic of occidental plotlines. Was it designed for an 86-year-old woman who, even in her so-called dementia, could not forget the past, who believed in the dead and knew they came to visit with messages truer than the dreary sound bites of consumer culture?

*

What I remember is the fall from the curb in the shopping mall. Nothing major, only a slip of the foot. My mother had been looking elsewhere, her eyes scanning the parking lot through the hazy Valley smog for my father’s navy-blue sedan. The doctors concurred: “a slight concussion, nothing major.” Yes, there was the scarring in the brain and some shrinkage had begun. “Perfectly normal for her age.” But something in my mother began to shift that day, something so subtle, so certain.

On that day my mother began to leave us.

*

Everything about our upbringing as Mexican American children revered our elders. With elders, we learned to offer a glass of water, a cup of coffee, the last empty chair in a room. We extended our arm for them to hold as they crossed a street, got out of a car, stepped into a bathtub. With elders, we learned to refrain from comment when we disagreed, endured long hours of visita without asking to eat, and never refused what was offered to us, no matter how stale the saltines. With elders, we also learned that if we made ourselves invisible enough, they might forget we were there and reveal all: stories with the power to conjure a past as stained and gray with intrigue as the aging photographs that held them.

As the century turned and my mother entered her mid-eighties, my sister and I began to warily approach the subject of my mother’s failing memory—to each other, to our father, and to her surviving younger sister and brother. “It’s normal,” everyone kept telling us. For a year or so prior, this had been my refrain as well, against my sister’s entreaties for “getting our mom some real help.” For it was JoAnn who lived within a half hour’s drive of our childhood home in San Gabriel. It was also my sister who endured my mother’s virulent denial about missed appointments, burned pots, forgotten phone conversations, lost keys and twenty-dollar bills, and seemingly delusional suspicions about our family’s treatment of her.

“Your sister hasn’t called me in weeks,” she’d complain to me over the phone in Oakland. “I don’t think I’ve even seen her in a month or more.”

I would call JoAnn to urge her to visit.

“I just saw her on Monday, brought them hamburgers. She’s forgotten.” What wrenched my heart the most was the futility of my sister’s actions. My mother suffered from “not-seeing” her because she could not remember. What she did remember was the nameless feeling of missing someone or something. Was it her unremembered self?

She was waning. Her world was becoming more insular. True, up to the last days of her life, Elvira would continue to exhibit great shows of affection when inspired, but slowly she began to pull away from us and into the world of her own preoccupations. This is not uncommon for elders where the physical requirements of aging often mandate their full attention. But in my mother’s case, that seemingly benign fall in the Montebello Mall initiated an entrenched self-absorption, thrusting her and her family into years of increasing agitation and disease.

My mother had never been an easygoing person, but gradually as her attention to what had been the normal routines of her life began to fade—cooking, cleaning, conducting familial relations—Elvira fell into great bouts of depression and fury.

Elders were to be honored at all costs; but when was the cost too high? We had given wide berth to the pure will and visceral knowing that defined my mother for most of our lives; this is, after all, what saved us. So how could we suddenly require her to surrender her will to us?

My mother’s 86th birthday marked a turning point for me when I began to loosen the hold on my conviction that my mother’s fuerza was enduring. On the night of her celebration at a nearby old-style Bavarian restaurant, which catered to elders of all kinds, my mother had opened a full table of gifts and responded to each present with perhaps a bit too much exuberance; this, no doubt, the result of the amount of wine she had drunk that evening.

But the following morning, suspecting Elvira hadn’t been all there the previous night, I asked her if she would like to see her presents. What? She didn’t remember getting presents. I brought out the pile of opened boxes, the tongues of white tissue hanging out from their mouths. She was elated at the sight of so many gifts. And so Elvira celebrated her birthday all over again for the first time. That was a good day, a day I could pretend not remembering was really due to the wine and normal for an 86-year-old and it isn’t called Alzheimer’s and it won’t get worse, because that day of not remembering made Elvira happy. In my heart, I knew differently.

*

Three months later, I arrive back home again in San Gabriel for a visit. It is not yet spring, but still a warming midafternoon. I expect to find my mother in her daily routine: scrubbing a pot here, folding a sweater there; walking from room to room, opening and shutting drawers and cupboards; transporting handfuls of clothing from one spot to another and back again. My father would have already spent a good part of the day in his office, a kind of makeshift construction of swelling fake wood panels, pressed against the crumbling stucco walls of the garage.

I enter the TV room (my childhood bedroom) and spy my mother, her head dropped back against the couch, her mouth open. She is so drugged that she isn’t even snoring. This is not the first time I have found her this way. I rush out to my dad’s office.

Since his retirement from the railroad freight yards, he had cultivated a steady stream of clients doing tax returns. Even during the off-season, he would manage to find much to do. Away from my mother’s purview, he submitted quarterly reports, worked on occasional audits, and ordered sports books and big-band music videos.

I interrogate him: How many pills is she taking? Let me see the prescription bottles. Hurried and nervous, he mumbles shamed inaudible responses as he hobbles with his walker back into the house. We rummage through the kitchen cupboards; the pills are everywhere, half-filled, refilled, there is no rhyme or reason to the amounts.

“She gets up in the middle of the night.” He stammers, “I . . . I don’t know what she’s taking.”

Right away, I am on the phone to my sister. She tracks down my mother’s doctor, who, unbeknownst to JoAnn, has given our mother drugs for depression. JoAnn and I soon dump the doctor when, during the quickly scheduled visit, he tries to assess my mother’s memory loss by having her remember the line “A rolling stone gathers no moss,” a sentence that means nothing to my unlettered Mexican mother. “Pendejo,” JoAnn and I agree about the doctor.

It is sometimes no more complicated than this: there are culturally stupid and lazy doctors who see elders as useless annoyances to be pacified with antidepressants. All the while our elders’ actions tell us the opposite; that they are not stupid, but suffering a deep inarticulate loss, about which they do not have the confidence to share, even with their most beloved. These old ones are holding their cards very close to their chest. They’ve been dealt a bad hand. They are bluffing and everyone knows it.

JoAnn finds my mother a gerontologist, a psychiatrist, and a social worker within a week. Her 30-plus years of working in the public school system, first as an elementary school teacher and then as a principal, where children are often last on the political agenda, taught my sister how to be an advocate and work that system for those who cannot. It may be what my sister is best at: the battle field of social welfare and justice—its black-and-white clarity, while the front lines of personal relationships are so much more difficult to negotiate.

Getting my mother to a doctor’s visit was seldom challenging. Elvira loved to be doted on by male doctors, especially handsome forty-something Asian American ones, which aptly described her new personal physician, who commented on how her fierceness and fine features reminded him of his own mother. In fact, Elvira flirted with doctors who catered to her. Although at times encouraging my mother’s flirtations served as an effective strategy for getting her to open up to her physicians, the game thinly cloaked her desperate attempt at control. Her disabling vulnerability teetered dangerously on the other edge of that coquettish smile, and the best of doctors could spot it. Her daughters feared and begged for her face to fall. Elvira needed help.

“No, todo ’stá bien. No necesitamos nada.” They, too, knew better than to challenge the dictums of their elders.A week later, my sister, mother, and father sit in the psychiatrist’s office. The doctor, a white man, wears a suit and sits behind a desk. My sister is grateful for this, hoping that without the telltale signs of a doctor, my mother might be tricked into answering questions she would otherwise reject. But the underlying tension is palpable: my mother fully suspects betrayal by her eldest daughter and husband at every turn. In my mother’s mind, the two are co-conspirators, plotting her submission to a culturally alien healthcare system intent on her demise. These are not her words, but it is her conviction.

The meeting with the psychiatrist goes smoothly enough until he asks my mother directly, “Your husband and daughter are concerned about your loss of memory. Have you noticed that you have been forgetting things?” And that’s all it takes.

After several years of the most blatant examples of my mother’s slipping hold on her own daily story—the inability to even eat a plate of food not buried under a hill of salt because she’d forgotten she had salted it only moments before—the doctor’s question throws Elvira into a frenzy of fury. He, too, is in collusion with these traitors, trying to ridicule and humiliate her. She bolts out of his office and into the reception area in a tirade of curses. In a way this was the best move my mother could have made since she had grown so expert at “keeping face” with the experts.

Stunned, the psychiatrist asks, “Does she often explode like this?”

“Yes,” JoAnn replies.

“She’s clearly bipolar. How long has this been going on?” And JoAnn had to laugh to herself at the psychiatrist’s on-the-spot diagnosis. “We’ve lived with this all of our lives,” JoAnn answers. “It’s only more aggravated now.”

I, too, laugh when my sister recounts this conversation and the entire episode on the phone to me later that evening. My mother’s intractability was as connected to her as sinew to muscle. It was, in fact, the very muscle of control that she had always held over her family. Her anger, and our fear of it, kept us in line as best a single mother (for Elvira felt herself alone in the rearing of her children) could.

Shaking hands with the psychiatrist, my father and sister exit his office only to discover my mother is not waiting for them outside the door. They fully believed that once inside the waiting room she would’ve recovered herself to save face.

“Does she wander?” the receptionist asks.

“No,” JoAnn answers, and does not add the truer statement, but she bolts to save her life.

My father and JoAnn hurry out of the medical building in search of my mother. My sister eventually finds her crouched behind a bush across the parking lot. From there, she was able to see her daughter and husband come out of the building. She could watch them search for her, never losing sight of them. My mother never once put herself in danger. That much control she still had.

*

The senior-care social worker turned out to be “una americana, a nice lady” who came to visit her. Vera seemed agreeable enough even when she had to do tests about which JoAnn and I had alerted the “nice lady” in advance. We wanted our mother’s memory assessed, not her education level, averting any situation that might shame our mother about her lack of schooling. There was no surprise when the social worker concluded, “Your mother needs care. She shouldn’t be left alone too much.” At this, my father drops his eyes, knowing he had endured my mother’s outbursts by sequestering himself in his garage office for long hours of the day.

So we agreed (at least in theory) to bring in an attendant to help with the cooking, the shopping, and some light housecleaning. She would monitor my mother’s meds and, no doubt, provide her with a little extra much-needed company. We had not consulted with my mother about this in advance, fearing that if she knew too soon, she would wear us down with resistance.

Days later, the attendant showed up for an interview and I was forced to tell my mother why she had come. My mother was incensed, of course, feeling that her last hold on the integrity of her home was dissolving before her eyes. She would barely talk to the woman, who did little to ingratiate herself to my mother. Maybe that was just what Elvira needed—a no-nonsense Mexican American woman, whom my mom could not manipulate. These are the stories we tell ourselves to justify decisions riddled with doubt. The other more traditional “señoras” we had previously hired to help out around the house were regularly sent away by my mother after a cup of reheated coffee and a few stale cookies from the cupboard.

“No, todo ’stá bien. No necesitamos nada.”

They, too, knew better than to challenge the dictums of their elders.

It was all arranged. Starting Monday, the attendant would begin to take care of my mother during the weekdays. Vera threatened to pack her bags. And so we pumped up our dad. “You gotta be brave,” we told him. But our father was not brave and when the attendant arrived that Monday morning, he predictably yielded to his wife’s threats and sent her away.

*

What we didn’t know was that the day before, our brother had shown up from out of state. Even when James lived within a few hours’ drive of my parents, he seldom visited them for longer than an evening, separated by long periods of absence. For the most part, his visits and communications numbered no more than two times a year, a restaurant meal squeezed between business meetings and golf rounds. Possibly for Anglo American families, this was acceptable; but for our extended familia mexicana, his distance remained, for all of us, completely incomprehensible.

“Cleave to your wife,” my brother’s trusted spiritual adviser, the monsignor, an elderly Irishman, had counseled, quoting Genesis. And with that, James settled on the outside what could never be resolved internally, the 40-year antagonism between his wife and his mother and sisters.

It had started as early as the age of 16, when James began dating an attractive and strong-minded “American” girl from our high school. Entering la familia Moraga was no doubt a culture shock for young Aileen. We all watched in stunned amazement when the things we took for granted in our home and that were loved by so many of our Mexican and non-Mexican friends alike were challenged aloud by the teenager.

She didn’t understand why James was required to kiss his mother and father and two teenaged sisters and abundant aunts and uncles each time he entered or left the house. It eluded her why an older brother might genuinely want to spend some time in his younger sisters’ company, if only to bang on the guitar and sing silly folk songs. She ignored the presumption that after months became years into their relationship she might offer to set a table or pick up a dish after dinner. The hardest part was that she made little effort to know our mother or, as Elvira put it, to leave the boy’s lap long enough to talk to [her], even if it was just pretend and she didn’t really give a damn about la vieja.

Aileen was not required to know us culturally. We did not feel similarly entitled.The last bit was just one line from our mother’s litany of discontent, spoken behind closed doors each time her son left the house, girlfriend in tow. The receding sound of tires against gravel was our cue to speak once James had maneuvered our family ’65 Chevy down the narrow driveway and out into the wider American world of awaiting promise.

In the beginning, our family remained in a kind of holding pattern in the young couple’s presence. What had worked so beautifully in public—the Student Body President/Captain of the Football Team going steady with the Cheerleader/Homecoming Queen—proved to be a miserable failure at home. We dashed and darted around the censored subject of the ill-fitting familial match, the silence growing increasingly strained and hostile.

My mother decreed that we were never to address the matter directly with our brother. As a result, Sunday dinner-table conversations were painful exercises in suppression, where Aileen freely expressed her right-wing political views about abortion and all those Mexican Americans who had suddenly turned Chicano, not to mention those un-American antiwar hippie protesters. Meanwhile, my mother would cut her eyes at us, a knife blade of censure flung across the dining room table, to silence me and my sister. I swallowed my rice and beans, along with my resentment, and lined up the toothpicks extracted from my taquitos like little foot soldiers along my plate: my own private 1968 army of dissent.

Aileen was entitled to her position because she was James’s girlfriend, but also because she was “American” in a way that we, as Mexican Americans, were not, especially my mother. Aileen was not required to know us culturally. We did not feel similarly entitled.

My father had nothing to say on the subject.

One day, unexpectedly, James decided to leave Aileen. By then, away at college, all he said was that she had been his only steady girlfriend and, well . . . they were both Catholics and, well . . . as my mother intimated, a young man has feelings. (The implication, of course, was that a young woman does not; and that the young man might need to go explore those “feelings” with other women first. All Elvira’s perspective.)

JoAnn and I couldn’t contain our excitement over the prospect of a free life for our brother, one that might lead him to a kind-hearted girl who might even love his family, too. I see now how much we perceived my brother’s choices through the prism of our own lives. James was the master of his own destiny. As females we would never know such freedom. Yet, culturally speaking, he was emotionally tethered to a Mexican family of women that had a direct stake in his choices. Perhaps the very onus of this was why my brother chose to leave us.

Suddenly, Aileen wants that long-awaited conversation with the much-maligned mother. One afternoon, she spills into our house crying, I love him. Convince him to take me back. Please, Mrs. V. And Mrs. V will do just that. At last, a player in her son’s life.

A few days later, James is home for the weekend, kicking back in his Bermuda shorts on the living room La-Z-Boy, watching TV. The late-morning sun pours through the sheer curtains. Elvira enters, sits down on the carpet at her son’s feet. She puts her hand on the naked part of his thigh just above the well-muscled kneecap, and tells him in plain words that she knows what he’s feeling.

“It’s only natural,” she says.

My mother would retell this story over and over again. It captured a brief moment in time when her word mattered in the life of her only son. But, more than this, it was a conversation about desire. This is what seemed to matter most to Elvira; that she knew the world of men’s desire well enough to advise him, even as it conflicted with the unbending Irish Catholic education we learned in our mission schools. My mother was well versed in the real rules of the world but was seldom asked to draw on them in guiding her son as he grew into American Christian manhood.

On that Bermuda shorts Saturday morning, my mother urged my brother to take Aileen back “because she is a good girl and would be a good mother for your children.” And so James did take her back. And true to biblical teachings, he would “cleave” to her. And the soon-to-be wife quickly dumped her soon-to-be mother-in-law, who had supported her in her time of need.

And we daughters chide, “We told you so, Mom. Why didn’t you just leave it alone?”

She responds, “Because I know how it is to love and be left like that.”

*

I am nine years old. It is a Saturday chore day. I am vacuuming the hallway.

“I have something to tell you,” my mother says over the blast of suction from the Kenmore. I catch the unease in her eyes and in the rope of dish towel she wrings at the waist of her apron. My heart quickens, and I hit the “off” switch with my sandaled toe.

“Yeah . . . ?”

“Mi’ ja, I was married before your father.”

They had met during the war, she says. And that’s about all she says. I am relieved to learn there were no other children, relieved to put a name and a story to the stranger’s portrait, foreign and blond, that lay at the thinning bottom of the red-and-white May Company box in the cupboard.

Many years later my mother revealed that she was the one who decided to divorce when she learned that her husband had reenlisted after the war. “It was so he could have other women,” she said. Too many women in too many ports is how I remember it.

*

Once in the early years of James’s marriage, my mother came to my sister and me and asked us to write his wife a letter. She wanted to explain her feelings, she said.

“If I have ever done anything to offend you . . .” was the line I remember most as she dictated the words to us. I also remember my mother’s utter shock to receive a letter back from her daughter-in-law, whose single response was “Examine your conscience,” refusing any gesture of reconciliation. The courage it took for my mother to swallow her pride in order to “write” the letter was just one measure of her love for her son. Perhaps it was the depth of this love that was so hard for Aileen. We would never know.

James remained inextricably Mexican; for it was my mother who had crafted my brother into the role of patriarch.Elvira is anxious. There is always so much to do. Is it lunchtime? Have we eaten? She goes to the kitchen, opens the refrigerator, and takes out half a tuna sandwich brought home from the coffee shop three days earlier, and puts it onto a plate for her husband. She sits and waits. She rises, goes to a kitchen drawer, removes a pile of unopened mailers, and crosses to her bedroom. She puts the mailers into a shoebox at the base of the closet. She returns to the kitchen, takes the coffee grounds from the pot of cold coffee on the stove, and dumps them into a mound on the pantry shelf. She shuts the cupboard. She sits again and waits. He’ll want coffee. She goes to the stove and turns on the near-empty coffee pot to high. She goes outside to call him in. The sun is setting into a hot muggy pink sky. She takes the hose to water her plants. The hose gets heavier every day. She hears men’s voices through the garage walls.

On the Sunday before the attendant’s scheduled arrival, my father escorts his son into his office, out of Vera’s earshot. There he confides the weight of his troubles—his volatile wife, his demanding daughters, his barely functioning but “I can manage” hips. When the subject of the attendant comes up, my brother responds, “Don’t listen to my sisters. She’s your wife. Do whatever you think is best.”

James gave this advice after assessing our mother’s condition over one meal; a meal during which Elvira put on that same coquettish face she had for the stranger-doctors. I had observed this for much of my adult life. As James grew more estranged, my mother grew stranger in her manner toward him.

On the few occasions when he visited without his wife, Vera seemed to “perform” herself. Once at an Easter meal, I watched as my mother twisted a full 90 degrees to talk with her son sitting next to her, literally turning her back on the rest of the family for the entire two-hour length of the dinner. She leaned into him like a lover, her makeup gleaming. When her son entered a room, all others were eclipsed and all was forgiven, or so she pretended. When she could still remember to pretend.

During that garage meeting, James also encouraged my dad to continue to postpone hip surgery if that was what he chose. When my father justified his inaction with “Your brother agreed,” there was no mistaking the bitterness in my sister’s and my responses. James had never endured the smell of urine on my father’s pants or the rank odor heat-baked into the broken upholstery of the driver’s seat of his car. My brother had no way of knowing my father’s real condition because he was never around long enough to observe that his father’s deteriorated hips couldn’t get him to the bathroom fast enough nor allow him to bend sufficiently to wipe well once he got there. He didn’t see him take a full five minutes to roll out of the driver’s seat of the car nor recognize his complete inability to move quickly enough to come to my mother’s aid.

In retrospect, the failed attempt at home care for my mother probably went the way it was supposed to. My mother’s fierce opposition and the stalemate of fear and resentment that was the fabric of my parents’ marriage may not have allowed for any other course of action. In this sense, my brother was blameless, constructing his advice on a fantasy marriage where the husband is not afraid of becoming an orphan and can monitor his wife’s well-being with the confidence of an endowed knowing. Perhaps my brother needed his illusions about his father, in spite of evidence to the contrary.

My brother’s authority, as the eldest and a male, went unchallenged within our family. In this respect, James remained inextricably Mexican; for it was my mother who had crafted my brother into the role of patriarch, the same role her elder brother and father had occupied in her own life. His long absences notwithstanding, my brother’s word was law. In all other aspects of our cultura, James was, as he once described it, “just passing through.”

__________________________________

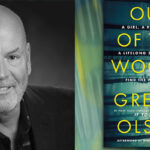

From Native Country of the Heart: A Memoir by Cherríe Moraga. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on April 2, 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Cherríe Moraga. All rights reserved.