On the Connection Between Chinese Folktales and American Comic Book Heroes

Gene Luen Yang Returns to the Adventures of Sun Wukong,

the Monkey King

I first heard about the monkey king from my mom.

When I was a kid, my mother used to tell me Chinese folktales before bedtime. My mother is an immigrant. She was born in mainland China and eventually made her way to the United States for graduate school.

She told me those stories so that I wouldn’t forget the culture that she had left. Even though I hadn’t ever experienced that culture firsthand, she wanted me to remember it.

Of all her stories, my favorites by far were about Sun Wukong, the monkey king. Here was a monkey who was so good at kung fu that his fighting skills leveled up to superpowers. He could call a cloud down from the sky and ride it like a surfboard. He could change his shape into anything he wanted. He could grow and shrink with the slightest thought. And he could clone himself by plucking hairs from his head and then breathing on them. How cool was that?

Eventually, though, I moved on to other kinds of heroes. One day when I was in the fifth grade, my mom took me to our local bookstore in San Jose, California. There I bought my first American comic book off a spinner rack in the corner of the store. Superman, Spider‑Man, and Captain America soon replaced Monkey King in my heart.

I became obsessed with comic books. I loved them so much that I went on to pursue a career in comics. Today I am a professional graphic novelist. My most well‑known book is American Born Chinese, published in 2006. Monkey King is one of my protagonists, but the book isn’t a direct adaptation of my mother’s stories. Sun Wukong occupies too high a pedestal in my mind. I wouldn’t dream of attempting a project like that.

Instead, I invited Monkey King into my story so that I could talk about the uneasiness of growing up Asian in America. The character I knew from my childhood expressed his emotions without reservation. I needed him to emote on my pages.

I invited Monkey King into my story so that I could talk about the uneasiness of growing up Asian in America.

For research, I tracked down an English translation of Journey to the West, the centuries‑old Chinese classic that first told the monkey king’s story. Reading it was the first time I encountered him on my own, without the filter of my mother.

Turns out, my mother was pretty faithful. As I read it, I realized that American superheroes hadn’t replaced Sun Wukong in my heart after all. Superman, Spider‑Man, and Captain America were simply Western expressions of everything I loved about the monkey king.

Superman’s epic battle with Doomsday echoes Monkey King’s epic battle with Red Boy. Spider‑Man’s struggle against his own ego in the bowels of a pro‑wrestling arena echoes Monkey King’s struggle against his own ego in the bowels of a mountain of rock. Captain America’s friendship with the Hulk, a thickset former foe, echoes Monkey King’s friendship with Pigsy, a thickset former foe.

This story about a monkey with superpowers has lasted for centuries because it captures something essential about our experience. Sun Wukong might be a monkey, but his anger, anxiety, and arrogance are all too human. We all know what it feels like to be disrespected. We all know what it’s like to lose control. We’ve all yearned for spiritual enlightenment. And we all know that the effort needed for enlightenment sometimes feels like a golden band that can squeeze the life out of us at any time, without warning.

The monkey king’s story reverberates across continents and cultures. Journey to the West is the very definition of timeless.

And that’s why new translations like the one you’re about to read are so important. They brush off the dust so that we can rediscover what is lasting.

My mother now has Alzheimer’s. She’s forgotten all of the stories she used to tell me when I was young, but I remember. In many ways, I’ve built my entire career on those moments before bedtime. With every comic book and graphic novel that I create, I am trying to recapture the wonder I felt when my mother would regale me with tales of Sun Wukong, the monkey king. I hope reading this book fills you with that same wonder.

Because I want you to remember, too.

__________________________________

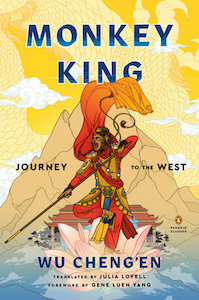

Excerpted from Monkey King by Wu Cheng’en, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Foreword and Monkey King illustrations copyright © 2021 by Gene Luen Yang.

Gene Luen Yang

Gene Luen Yang writes, and sometimes draws, comic books and graphic novels. As the Library of Congress’ fifth National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, he advocates for the importance of reading, especially reading diversely. American Born Chinese, his first graphic novel from First Second Books, was a National Book Award finalist, as well as the winner of the Printz Award and an Eisner Award. His two-volume graphic novel Boxers & Saints won the L.A. Times Book Prize and was a National Book Award Finalist. His other works include Secret Coders (with Mike Holmes), The Shadow Hero (with Sonny Liew), New Super-Man from DC Comics (with various artists), and the Avatar: The Last Airbender series from Dark Horse Comics (with Gurihiru). In 2016, he was named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow.