On the Challenges of Writing About Death

Annie Lyons: "I wanted to give a voice to the discussions I wish I’d had with my own mum."

“I want to write a story about death.”

My editor blinked at me. She was barely into her twenties and thoughts of her own mortality were decades ahead. I, on the other hand, had just turned 40, and it was turning into something of a preoccupation for me.

“Death,” she whispered, as if the mere mention might invite it into the room.

“I’ll make it funny. Uplifting even. It won’t be depressing at all.”

She raised her eyebrows doubtfully. Writers are always saying stuff like this. We make up things for a living. It’s in our nature. Serial liars. With beautiful notebooks. “I’ve got other ideas,” I said. We both exhaled.

I left the meeting and the idea stayed with me, bubbling in my brain for the next few years like an unwatched pot. To say that I was obsessed with death was perhaps an overstatement; it was more of a casual hobby, like knitting or making macramé pots. I knew this obsession stemmed from my own fear of death and a sneaking suspicion that the best way to deal with that fear is to talk it out or, in my case, write a book about it.

Like long-lost relatives turning up out of the blue or locked doors leading to who knows where, death has been catnip for writers since the beginning of time.

A couple of years and a couple of published novels later, I read a book called With the End in Mind by Dr. Kathryn Mannix. My mind was blown. Here was a woman who walked alongside death every day in her role as a palliative care doctor. She didn’t understand why we couldn’t talk about it either; why we couldn’t even use the “D word”; why so many people died without telling their loved ones how they’d like their story to end. I was inspired and galvanised into action.

The biggest question was how to turn this idea into a story while bringing fresh perspective on death. Like long-lost relatives turning up out of the blue or locked doors leading to who knows where, death has been catnip for writers since the beginning of time. It allows us to up the emotional stakes and break readers’ hearts (I have never got over the death of Beth in Little Women and I never will). It enables writers to view death and its aftermath in a novel way, as in The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold, which is told through the eyes of the deceased protagonist. It even provides authors with license for astonishing originality, as in The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, by casting death as a character, offering commentary on humanity and all its darkest flaws.

I knew I wanted to write something that wasn’t about the aftermath of death or that had any fantasy element. I wanted to look at death before it happens, to be as honest as possible about how we live and how we die, and of course to do all that without making it depressing.

The next challenge was to find a character with broad enough shoulders to carry this topic.

I can’t remember the exact moment Eudora Honeysett arrived in my life. In a way, I think she’d always been there, sitting quietly with her crossword and a cup of perfectly-steeped tea. Having grown up during the Second World War, she shared many qualities with my own mother: resilience, stoicism and an acceptance of death as being part of life. However, it was clear that Eudora needed another element to her story; someone to help her question her decisions and view life with fresh eyes. Enter Rose, with her cheerful curiosity, who does just that through a combination of startling honesty and wide-eyed kindness.

I wanted to give a voice to the discussions I wish I’d had with my own mum; to start some necessary conversations about how we live and how we die.

Writing scenes featuring Eudora and Rose was rarely a chore. I always enjoy creating child characters, as they gift you the innate ability to cut straight to the heart of the matter whilst keeping the tone light. However, writing a scene in which Eudora has to help Rose’s mother deliver her baby at home was more of a challenge. This needed to pack an emotional punch as Rose begs Eudora for help and she is forced to take action where she would normally retreat. The moment is laced with drama and emotion as Daisy is born, but Eudora is also confronted with painful memories of her sister, which play out as she holds a newborn baby in her arms.

I was six months into writing the story when my own mother became ill. In true Eudora fashion, she had a heart attack but didn’t realize for three days. She spent the next two months in the hospital, and as her condition declined and it became clear that she was dying, I felt utterly helpless and unprepared. Mum and I had rarely discussed death. Her parents lost brothers, uncles and friends during the war. They didn’t talk about death because it happened to every family. It was commonplace. That Blitz spirit served my mum well, but it meant that we didn’t have those important conversations about how she’d like her own death to be.

Ultimately, the decision was taken from her. She died in the early hours of Christmas Eve 2018 surrounded by the fairy lights and tinsel I’d hung around her bed in my feeble attempt to keep things normal.

It was a strange kind of therapy to be finishing Eudora’s story after Mum died, but oddly comforting too. I wanted to give a voice to the discussions I wish I’d had with my own mum; to start some necessary conversations about how we live and how we die. We all have a choice. Ultimately, we should be able to laugh and cry as we accompany our loved ones on their final journey; to celebrate their lives and say goodbye properly. I think we owe it to ourselves and those we love to face death, not with fear, but with hope and honesty. I know Eudora and Rose feel the same.

__________________________________

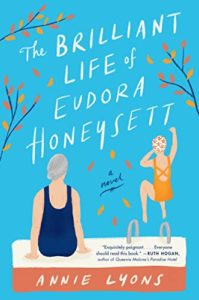

The Brilliant Life of Eudora Honeysett by Annie Lyon is available via William Morrow and Company.

Annie Lyons

After a career in bookselling and publishing, Annie Lyons published five books in the U.K., including the bestselling Not Quite Perfect. When not working on her novels, she teaches creative writing. She lives in south-east London with her husband and two children.