On the Art (and Artifice) of the Miniature

For Amber Sparks the Dollhouse is a Whole World

The Kitchen

It starts here: in the kitchen. Not a full-size kitchen, of course, but rather a miniature replica of a kitchen, a tiny kitchen with a tiny table where two tiny dolls sit, blank-eyed and smiling and ready to eat an invisible meal.

This is the setting in my favorite Sesame Street segment, set to a song that will get stuck in my head for the rest of my life, though I do not know it yet. “One, two, two little dolls. One, two, two little chairs. Two little dolls, two little chairs, two little girls, and a little dollhouse.” I watch the small, squat television on my grandmother’s brown kitchen counter, drawn in by the tiny china cups and the tiny silver spoons, everything so delicate—and then laugh, surprised and delighted, as two little cats wreak havoc on the dollhouse and its carefully set table. The two little girls on the television laugh with me. It is my first exposure to this enchanted, ephemeral world, and also my first lesson into how funny it can be, introducing chaos into order.

When I am older, I am given a large, sturdy wooden dollhouse for my birthday. It’s newly painted, beige with brown trim and a real wooden staircase. The floors are made to look like parquet. My father tells me it was originally built by my great-grandfather, in the 1920s. I don’t know what that means, not really, but I like to stick my face into the rooms and look out the tiny windows, set with real, wobbly glass.

My father makes color copies of famous paintings and gilt frames for the walls of the living room and bedrooms. But it’s the kitchen that fascinates me. I have been reading The Borrowers, and in that book about a family of doll-sized people, the kitchen is the center of the household. It’s where Arietty’s mother Homily reigns, where she uses a carefully-built stove to melt bits of the massive sugar cubes Arietty and her father “borrow” in their roamings around the humans’ house.

My own little doll family has no memories, no past, no future. They are perpetually unperturbed.

When I finish the book, I immediately start it over again, lingering over each description of a human object made useful to tiny beings: spools of thread turned into tables, clothespins reborn as rolling pins.

In my own dollhouse, my dolls are not forced to improvise. Thanks to a German company called Playmobil, they have their own tiny silver spoons, their own china cups and saucers. They have bright copper pans hung on hooks above a shiny silver stove, a wicker basket full of tiny plastic items (a meat tenderizer, a rug beater) that I won’t even recognize until later in my life, when my daughter inherits the dollhouse.

Sometimes I spend hours setting everything in the house up just so: daughter perched at the piano, sheet music open to Beethoven’s Fifth; son kneeling in front of his toy train; mother in the kitchen, wearing her starched white apron and setting the table for lunch; father in the bathroom, ready to flush the old-fashioned WC with a chain. Then I grab my cat and position her in front of the dollhouse. She’s too tall to enter the rooms, but she likes to swipe a paw through them, knocking over persons and things and furniture and paintings.

I can’t explain why it’s so satisfying, but it makes me feel safe, somehow. The chaos contained, easy to clean. And a plastic family who lie scattered across the floor, still blank-faced and smiling. Not like the Borrower family who, at last exposed to the humans, must shift to a new home. My own little doll family has no memories, no past, no future. They are perpetually unperturbed.

The Living Room

Wes Anderson, like a handful of other directors working today, prefers to use miniatures and matte paintings and models in his films, instead of CGI effects. (In film, of course, miniature doesn’t quite mean doll-like, but simply sets built to less than full scale.) One of the most frequent criticisms his films receive is that they are too precious, too concerned with style over substance. I bridle every time I read one of these criticisms: not just because I love his films, which I do, but because it is upsetting to me that so many people’s default in entertainment is external, explosive, big.

They are dollhouses and they are worlds; they are living rooms for loneliness.

Anderson’s films are films of interiority, of precise, contained rooms, with precise, contained people using precise, contained language while they slowly drown on the inside, human hourglasses filling quietly from within. I am from the Upper Midwest; I understand these people very well. Anderson’s color-drenched style is not exactly the colorless Protestant variety I know, but I recognize the stillness, the immense longing inside these tiny humans stamped onto Technicolor-like vistas, confined to bathtubs and couches and tents and living rooms and ordinary human hearts.

These perfect sets remind me of the little rooms set into walls that I have seen at the Chicago Art Institute, a set of perfect architectural and interior design wonders called the Thorne Rooms. These rooms are impossibly intricate and graceful, and range from an Art Deco living room to a Gothic cathedral altar. They were envisioned and commissioned by Narcissa Niblack Thorne in the 1930s, and are nearly miraculous to behold. (Thorne was married to the heir to the Montgomery Ward fortune; she could afford to spend the cash to make them miracles.) The details are minute and intricate, down to the miniature paintings and sculptures created by contemporary artists.

There are no people in these rooms, though. They are empty, lovely but sterile, unlived in. They are showrooms, not rooms for life. They seem to be waiting for someone, for something. They hold a kind of beautiful sadness. This is unlike the beautiful sadness in Anderson’s films, which is entirely full (often to bursting) with humans and their shattered interiors.

In The Grand Budapest Hotel and Asteroid City, two of Wes Anderson’s grandest films (and my favorites), Anderson used miniatures to create some of the settings. They are dollhouses and they are worlds; they are living rooms for loneliness. And they are anything but lifelike. The precision of the set decoration, the perfectly symmetrical framing, is the point.

“The particular brand of artificiality that I like to use is an old-fashioned one,” Anderson has said of his miniatures sets and models. It’s all artifice. In Anderson’s films, we cannot possibly hope for connection, but we do hope, we yearn, we never stop trying to pull back the curtains. We are all dolls, blank-eyed, full of longing inside while we lie on the floor of our own grief.

The Back Yard

When I am ten, I go to the theater with my family to see a movie starring the nerdy guy I know from Ghostbusters and Spaceballs. In it, he plays a sort of domestic mad scientist, an absent-minded professor type who accidentally shrinks his own children (and the neighbor kids) in an experiment gone wrong. The predictable hijinks ensue: the kids get thrown out with the trash and must navigate their own back yard, turned jungle. They befriend an ant, ride a bee, and briefly consider the existential implications of being ¼ inch tall forever—but this being an 80s comedy, they mostly bicker, run from giant raindrops, and, in the teenagers’ case, make out.

They become something more, part of the great menagerie of the wild.

It looks fun, being small! But this film is also the opposite of what Wes Anderson is doing. It’s all exteriors, giant insects, the great unknown. Something similar happens to the toys in Toy Story, the fairies in Disney films, and even to the tiny aliens in the French animated film Fantastic Planet: these are the stories of what happens when the dolls leave the dollhouse. They have traded security for adventure, and they may not survive the bigness of the world outside. But they’re determined to break free of that interiority at all costs, to expand their limits and experience something more. They transcend mere dollhood in these films, even the dolls in the Toy Story movies. They become something more, part of the great menagerie of the wild.

The Attic

There are dark things at work in the dollhouse, too. At twelve I read a book called The Dollhouse Murders, in which a child’s grandparents are brutally murdered, and the dolls in her dollhouse come to life each night to reenact the murder until she figures out who the killer is. The protagonist eventually overcomes her fear, but I put a bedsheet over my dollhouse at night just in case.

Similarly, in a book I adore, Behind the Attic Wall, a girl finds a secret room full of dolls who come to life when she visits. The visits are cheerful and full of magic until she realizes the dolls are the ghosts of the prior inhabitants of the house, who died in a terrible fire.

The very small is under an even darker shadow in the Are You Afraid of the Dark? episode I watch as a kid where a witch shrinks children and traps them in a dollhouse; and the shadow is almost too dark to bear in The Incredible Shrinking Man, when the titular hero finally shrinks down smaller than an atom, crying out to the heavens in both exaltation and horror as he goes out like a candle.

Much later, as an adult, I will have the opportunity to attend a special museum exhibit to see Frances Glessner Lee’s Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. Lee was an artist who helped pioneer the field of forensic science. She constructed tiny dioramas of death scenes, in order to give detectives practical experience in studying and analyzing a crime scene.

I am the first to shout out the correct solution; I have been studying the darkness in dollhouses for a very long time.

In person, the dioramas are larger and more colorful than I’d expected, the scale bigger than a typical dollhouse. They are also incredibly detailed; Lee sewed minute lace on the doll victims’ clothing, sculpted water in bathtubs, built furniture and knitted rugs and knotted a noose hanging from a rafter in a barn. She painted dolls’ faces with bruises and blood and signs of decomposition. She spattered walls with red in specific patterns, lined up miniscule bullet holes in walls and doors.

Some of the scenes are based on real crimes, but details have been changed. Her studies are still in use in police training today, so the solutions to each are kept a close secret and have never been revealed publicly. Only one has been shared: a strangely tender scene of a murdered family, wife, baby, and husband shot to death in their home. During our tour of the museum, my group is asked to solve the mystery. I am the first to shout out the correct solution; I have been studying the darkness in dollhouses for a very long time.

The Conservatory

If there is terror in small things, there is safety, too. There is retreat, there is opportunity for enclosure. In her book On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Susan Stewart writes that “the interiority of the enclosed world tends to reify the interiority of the viewer.” We can act out our own dramas in the security of a static space.

In the Twilight Zone episode “Miniature,” a young Robert Duvall plays a gentle man who has difficulty relating to people in his life. He becomes obsessed with a dollhouse at his local museum, returning over and over to watch the beautiful doll who lives in it play piano and dance in her conservatory. She comes to life only for him. He becomes a doll in the house himself, granted the interior he has always wanted, the surety of sameness a great gift to him. It is a rare Twilight Zone, one that ends happily, if obligingly weirdly.

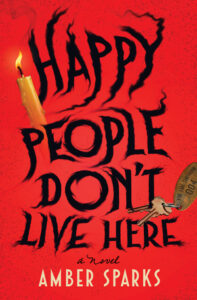

In my own new novel, Happy People Don’t Live Here, the protagonist finds solace in her mother’s dollhouse as a child. She retreats from a human house full of neglect and conflict to a doll’s house where she imagines an alternative family, a mother and father and child who love and care for one another. The dollhouse can also be a dream:

“Something rippled and she was on the other side, everything almost the same, with a difference. Her mother was awake, dancing, the martini glass and cigarette gone. Her father sat across from her, doing card tricks. Something opened up in there for Alice. Something double. She spent hours playing, looking at the dollhouse, staring at her face in that mirror, willing it to shrink down so she could inhabit this looking-glass world for good.”

Later, in adulthood, Alice makes miniatures for a living, inspired by artist Joseph Cornell’s boxes and the tiny fairies her mother owned, nestled in the head of a pin. But the miniatures are no longer for her, and they no longer offer a sanctuary. The rooms she makes now can only be inhabited by other people. Like that other Alice, she must give up the looking-glass rooms and find a place in her own world.

The Window

My daughter has the dollhouse in her room now; she is the fifth generation to own it and the fourth generation to play with it. She still has some of my Playmobil furniture, but the house has acquired some modern touches: tiny groceries, UPS packages, concert posters, and a flatscreen TV. The pull chain toilet has been lost, the clawfoot bathtub replaced by a shower with a frosted glass door. There are also Godzilla figures and Tinkerbell’s friend fairies and even Nationals baseball bobbleheads in the dollhouse; it is a crowded place these days. The glass windows are blocked by tables and a piano and a crib and a dressmaker’s dummy. There is pink sand all over the floor of the children’s bedroom.

I don’t know what, exactly, the smallness means to her, and I don’t ask; small things are private things.

But she loves the dollhouse, too. Sometimes she drags her lamp to the side of the dollhouse and shines it into the one window that’s not covered, and admires the effect, the sudden sharp shadows and bright shapes the light makes. I don’t know what, exactly, the smallness means to her, and I don’t ask; small things are private things.

I showed her the Sesame Street video the other day. I’d rediscovered it on YouTube after years of looking for it, of half-remembered snatches of song and the distinct memory of the cats’ heads bursting through the dollhouse doorways.

But she grew bored quickly, and turned back to her book, and so I watched it alone: two, three, four times in a row, with the uncanny sensation of watching myself watch it at three years old, small enough to put my whole head in a dollhouse, small enough to think a dollhouse was the world.

__________________________________

Happy People Don’t Live Here by Amber Sparks is available from Liveright, an imprint of W.W. Norton.

Amber Sparks

Amber Sparks is the author of And I Do Not Forgive You, The Unfinished World and Other Stories, and the short story collection, May We Shed These Human Bodies, as well as the co-author of a hybrid novella with Robert Kloss and illustrator Matt Kish, titled The Desert Places. She’s written numerous short stories, flash fictions and essays, which have been featured in various publications and across the web. Say hi on Twitter @ambernoelle.