On the Activism of Marlon Brando, Before the Fame

Agitprop, Israel, and the Shape of the World After WWII

At the Park Savoy Hotel on West 58th Street, the pay phone in the first-floor hallway was jangling. When someone picked it up, they heard Bill Liebling ask if Marlon Brando still lived there. No, Liebling was told, Marlon had left the hotel some time ago, leaving no forwarding address. But the bohemians who still lived there remembered him fondly. There was talk that he’d gone “on the road”—not with a show, but with a carload of activists fighting for a political cause.

From the window of a speeding passenger train, Marlon stared out at the rapidly changing landscapes of Pennsylvania and western New York. Everywhere, it seemed, new housing was going up, guaranteed by federal programs for qualified returning veterans, complete with the latest appliances and the requisite picket fence. Now 23 years old, Marlon was fascinated by how the world was rebuilding itself—a task he was attempting for himself as well. After three unrewarding years in the theater, disillusioned and personally drained, he had needed something to believe in, something weightier and more meaningful than the superficiality of the theater. And so, for much of the spring and summer of 1947, he’d been crisscrossing the country with the American League for a Free Palestine, advocating for a Jewish state in the Middle East.

“I am now an active and integral part of a political organization,” he wrote home proudly. “My job is to travel about the country and lecture to sympathetic groups in order to solicit money and to organize groups that will support us.” A three-week training program had left him thoroughly familiar with and committed to the ALFP’s mission. After the horrors endured by Jews during the war, Marlon believed the only moral restitution was an independent Jewish state. The Western powers had “trampled” on the Jews, he said, and it was time for the British occupiers of Palestine to return to the Jews their ancient homeland. To his family he wrote, “You wouldn’t believe the injustices and cruelties that the British Colonial Office is capable of.” He assured them he was “not being rash” in his judgment, and sent home some literature to prove what he said was true.

Marlon’s attraction to the ALFP was not surprising. Both Stella and Luther Adler were on the organization’s board. The mission of the group was the mission of Marlon’s family, his emotional family, and so, quite naturally, it also became his.

*

At Beth Hillel Temple in Kenosha, Wisconsin, Marlon walked up to the podium, a little nervous and awkward. To the audience he seemed even younger than he was. In New York, he’d developed a reputation among Broadway aficionados as the powerhouse who’d let out that heartbreaking howl in Truckline Café, but here in the land of lakes and cheese, even that minimal recognition was denied to him. In Kenosha, Marlon was just a good-looking, slightly gangly young man in an ill-fitting beige suit. He made these tours with other young, largely unknown New York actors who supported the cause of the ALFP; joining him in Kenosha was Jerry Solars, who’d appeared at the Barbizon-Plaza Theatre in the comedy We Will Dream Again in April 1947. They were billed grandly as “actors from the New York stage,” even if no one west of the Hudson River knew who they were.

Yet when Marlon began to speak, the people in the audience sat up. “The British Colonial administration of Palestine,” he declared, his voice rising an octave, “is guilty of violating human rights at the very moment European Jews are most in need of sanctuary.” His blue-gray eyes flashing, he demanded that the United States pressure Britain into granting “Hebrew national citizenship” to all Jews in Palestine, Europe, and North Africa who wanted to be part of a new Jewish state.

The audience, mostly middle-aged Jewish immigrants from Russia and Poland who had come to the United States well before the war, burst into applause. Some had been unconvinced of the necessity of a Jewish state, but after hearing Marlon and the other speakers from the ALFP, many were now on board. The applause from that Kenosha synagogue “meant far more to Marlon,” Ellen Adler thought, than any he had been given by any Broadway audience.

After seeing the harrowing newsreels of concentration camps, Marlon had come to believe that the Jews “had to do whatever was necessary” to acquire their own state.He’d found a way to address what he’d once described to his parents as “the bitterness, fear, hate and untruths” of the world, a condition he’d vowed “to do something about” soon after arriving in New York. The instinctive leftist politics he’d grown up with were finally given voice. “The work that we’ll be doing,” he told his parents after joining the ALFP, “won’t be easy by any matter of means. It is a tougher and vastly more responsible job than anything the theatre could offer. I’m going to try to do my best to add my little bit.”

His “little bit” quickly became the center of his life. With Stella and Luther and others, Marlon debated tactics about the best way to achieve their goals. He tended to be more radical than some in the ALFP; he sided with the militants, for example, who argued that “terrorism and military action were necessary to wear down British resistance and lead to the early creation of Israel.” After seeing the harrowing newsreels of concentration camps, Marlon had come to believe that the Jews “had to do whatever was necessary” to acquire their own state.

This was the sort of thing that fired him up. This was the sort of dialogue that kept Marlon alert and engaged: justice and freedom and human rights. The conversations of his actor friends, analyzing the move away from didacticism and toward psychological exploration in the American theater, bored him to death. The war, he believed, had imposed a greater urgency for civic responsibility. “I had a sense that though the world had gone through a cataclysm, little had changed,” he would recall. “Black people were still being treated as less than human, there was still rampant poverty and anti-Semitism, and there seemed to be as much injustice as before.” Only whites, for example, could apply for most of those new housing tracts being built for returning veterans. A persistent voice in Marlon’s head was telling him that “acting was not an important vocation in life when the world was still facing so many problems.”

The young man who had been denied access and expression for much of his life, who’d been kept back and discouraged, who’d been told repeatedly that he didn’t matter, felt far more drawn to social advocacy than he did to acting or the theater. For others, success in the theater might provide a sense of personal affirmation; the applause might fill up some empty part inside them. But not for Marlon. He desired “more concrete results” than that, Ellen Adler said; he wanted “a change in the entire world, not just his world.” Away from the theater, “working for something he believed in,” Ellen said, “Marlon was much happier.” To his parents, he declared that working for the ALFP left him “stimulated more than [he’d] ever been.”

Perhaps, then, this was his calling. Perhaps, Marlon thought, political advocacy or social justice work was what he ought to pursue. During a visit to Washington, DC, with the ALFP, he witnessed firsthand the racial segregation in the nation’s capital, and it left him furious. “I felt I had a responsibility to do something about it,” he said. All his life, injustice had followed him—a different sort of injustice, certainly, than that faced by Negroes or Jews, but injustice nonetheless. Marlon seemed to feel that he could make up for what he called “the captivity” of his youth by working for the freedom of others. “I knew what it was like to feel hopeless,” he’d say. “So that was the sort of work I should’ve been doing. Not acting.” Stella, still convinced of her protégé’s potential to be great, argued that he could combine his political passion with the theater.

And for a few months at the end of 1946, Marlon had done just that, costarring in A Flag Is Born, a play produced by the ALFP to advance the cause of a Jewish state. The British navy’s seizure of a Jewish refugee ship headed for Palestine in March 1947 had convinced the ALFP of the need for a high-profile response. “To see the British soldiers taking people off the ship forcibly,” Marlon said, “with guns pointed at them, and putting them behind barbed wire in Cypress [sic, Cyprus], seemed to me to put the world topsy-turvy, because what in the world had we fought for if not liberty and the right for people to be protected?” A Flag Is Born was the ALFP’s strongest salvo yet against British hostility and American inaction. Written by famed screenwriter Ben Hecht, the play was directed by Luther Adler, whose elder sister, Celia, starred alongside Oscar-winning Hollywood actor Paul Muni. Marlon was the only non-Jew in the cast. He played a concentration camp survivor headed to the promised land of Palestine. Opening on September 4, 1946, for a limited run at the Alvin Theatre, A Flag Is Born was successful enough to be given an extended run at the Adelphi, where Marlon had made his Broadway debut, in Bobino, two years earlier, in a giraffe costume.

The play was, in fact, Piscator-style pedagogic theater: “an obvious bit of propaganda,” Variety called it, with “the defects of all propaganda.”Marlon, who rarely idolized anyone, was awestruck by Muni. “The best acting I ever saw in my life,” he said. That was because, he felt, Muni’s acting was in service to something greater than the play; the performance mattered well beyond the proscenium arch. “Art for art’s sake” was abhorrent to Marlon. In the months before signing on to Flag, he’d read Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh and thought very little of it, declining to pursue what would become O’Neill’s latter-day masterpiece. Iceman wasn’t about anything Marlon considered “timely”; there was nothing in it, he thought, that mattered to “the practical here and now.” A Flag Is Born, by contrast, was about as “now” as one could find in the theater.

The play was, in fact, Piscator-style pedagogic theater: “an obvious bit of propaganda,” Variety called it, with “the defects of all propaganda.” Yet Marlon, and the Adlers, overlooked those defects, because the play filled an urgent need. Reviewers tended to agree with them, turning blind eyes to the play’s gimmicks and moralizing; its “stirring message,” Variety concluded, “demands attention.” To Marlon, his work in A Flag Is Born was the most important acting he’d ever done. This mattered; most everything that had come before had not. As payment, he accepted only the Actors’ Equity minimum; any money the play made, Marlon agreed, should go toward the ALFP’s efforts to establish the state of Israel. Variety praised his “emotional intensity” in the part, but it was offstage where Marlon’s zeal really came alive. When he left the play in late November 1946, replaced by Sidney Lumet, he was ready and eager to start touring with the ALFP.

But before he could do that, he needed one other thing: money. Since he’d made next to nothing during his two months in Flag, he was now broke.

That was how he had ended up with Tallulah Bankhead in a play that meant nothing to him. Eagle Rampant was an English translation of a Jean Cocteau play. Bankhead was a friend of Marlon’s agent Edie Van Cleve, which was how he’d gotten the role. After feeling empowered during A Flag Is Born, part of a constructive and vital movement, he chafed at being involved in what was essentially a vanity project for an aging actress. With Bankhead “constantly drinking and sloshed most of the time,” Marlon came to think of her as “a Duesenberg [automobile] that’s been hit by four trains.” Bankhead played a fictional European queen, Marlon the assassin hired to kill her. The antagonism backstage was nearly as lethal.

The play opened in Wilmington on November 28, 1946, then moved on to Washington, Boston, Hartford, and New Haven, where, on January 2, 1947, Marlon was abruptly fired and replaced by Helmut Dantine. As much as Marlon had disliked the play, he admitted to being “vaguely depressed” boarding the train for New York. The expulsion undoubtedly summoned a barrage of old memories, from Shattuck to Sayville. For the rest of his life, he would badmouth Bankhead, claiming she’d put the make on him (“plunging her cold tongue into my mouth like an eel”). While certainly not out of character for the bawdy Tallulah, Marlon’s claim that he was fired because he wouldn’t sleep with her is dubious, given the stack of bad reviews he’d accumulated since the play’s premiere. In Wilmington, Variety wrote that he failed “to impress as a revolutionary poet”; the Boston Globe concluded that he was “not equal to his role”; and the Hartford Courant called him “ineffectual as assassin and poetic inspiration.” With notices like that, it was a wonder he lasted as long as he did.

To Marlon, Eagle Rampant was the worst kind of theater, empty and artificial. He was there only for the cash he could make. But even that came to naught when, on the train back to New York, someone stole $2,000 out of his bag, leaving him with nothing to show for all his aggravation. “I arrived in New York with holes in my socks and holes in my mind,” he said. As far as Marlon was concerned, he was done with acting. He happily embarked on his seven months of travel for the ALFP.

He didn’t return to New York until the late summer of 1947, just as Bill Liebling set out looking for him. Once again, Marlon was broke; working for a nonprofit never made anyone rich. He didn’t care about being rich, of course, just about having enough money to pay the rent at his new apartment at 37 West Fifty-Second Street. He also wanted to take dance and flute lessons, plus he was saddled with doctor’s bills for Celia, who’d had some bad times.

Marlon was dependent, yet again, on his father for a regular allowance. Dodie had left New York and returned to her husband, and so the old family charade had resumed. As long as his mother was estranged from her husband, Marlon could be free of him as well. But once his parents reconciled, Marlon once again became the little boy trying to make his father proud. “I must learn how to handle money myself,” he wrote home. “You’re damn swell to offer your dummy son help.” Marlon Senior had recently gone into business for himself and was having difficulty setting up sales accounts; hoping to make some money on Eagle Rampant, Marlon Junior had told his father, “It won’t be long until I can give you the world.” That plan had gone bust. It seemed he might be doomed to being the “dummy son” forever.

That late summer of 1947, Marlon was in the position he usually was in when an acting offer came his way: broke and without any other options. When the grapevine finally caught up with him, Marlon learned that Bill Liebling was looking for him. And so, on a hot, humid August day, he hiked over to Fifth Avenue to see what all the urgency was about.

__________________________________

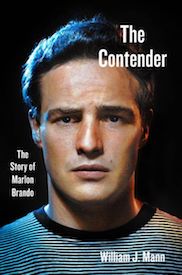

From The Contender: The Story of Marlon Brando by William J. Mann. Copyright © 2019 by William J. Mann. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.