For five years you tried to be young. When you left high school—just a few days after you started—you were hired at the village factory, but you didn’t stay there long, either, barely a couple of weeks. You didn’t want to repeat the life of your father and his father before him. They’d gone straight to work the moment childhood was over, at fourteen or fifteen. They had gone, without any transition, from childhood to exhaustion and getting ready to die, without ever having been granted those few years of oblivion toward the world and reality that others call youth (even if that’s a silly way of putting it, those few years of oblivion others call youth).

But for five years you fought for youth with all your might. You went to live in the south of France, telling yourself that life would be better there, less oppressive, if only because of all the sunshine. You stole mopeds, you stayed out all night, you drank all you could. You lived as intensely and aggressively as possible, because you felt that these experiences were stolen—and this, this is my point: there are those to whom youth is given and those who can only try desperately to steal it.

Then one day you stopped. I think it was a question of money, but not only that. You stopped everything you were doing and went back to the village where you were born—or the one right next to it—and you got yourself hired by the factory where your whole family had worked before you.

A classic pattern: because you felt that you hadn’t lived your youth to the fullest, you spent your whole life trying to be young. That’s the trouble with stolen things, like you with your youth: we can never quite believe they are really ours, and so we have to keep stealing them forever. The theft never ends. You wanted to recapture your youth, to reclaim it, to resteal it. Only those who have always had everything given to them can truly feel what it is to possess. A sense of possession is not something one can acquire.

One of those attempts to be young again—to be young at last—took place when you were with your friend Anthony. Do you remember? The two of you were in the car and you spotted the police behind you. You’d both had a lot to drink. They would have taken your license away if they’d stopped you, and would never have given it back. You thought they were tailing you, so you hit the gas. You took off, as if they were in hot pursuit. You ran lights, you went faster and faster. I imagine you were acting out the chase scenes you watched all night on TV, with American cops and robbers: even in the most intense moments of our lives, it seems to me, we continue to act out scenes and roles we’ve seen in books or movies. You drove till you came to a river.

You both leapt out of the car and into the water to keep from getting caught by the police (I’m not sure if the police were ever actually chasing you in the first place). You swam—you, who were more frightened of water than anything, who were afraid of taking a bath, that’s how bad your phobia was, you swam in the freezing water, and together you climbed out a few hundred feet downstream. For a long time you waited there, up to your ankles in mud, soaked to the skin, hoping the police would go away, and then you came home to my mother’s, your clothes soggy with water smelling of muck and of fish. The water was pouring off you, off your bodies onto the floor, the drops streaming down the fabric of your clothing and puddling in silence at your feet. You didn’t use to tell this story yourself, since you never talked much, but when my mother told it—as she often did, two or three times a month—you would smile and say, It’s true we had a good laugh. You had managed to retrieve a moment of your youth.

You were fascinated by all technological innovations, as if, through the novelty they embodied, you could infuse your own life with a newness to which you were not entitled. You commented, in a voice part envy and part admiration, on ads for new phones, tablets, or computers. You didn’t buy them, they cost too much. You made do with gadgets traveling salesmen hawked at the village market: a watch that went backwards, a machine for making Coke at home, a laser that could project the image of a naked woman on a wall a hundred yards away. In general, these memories are inhabited more by things than by people.

You lived out your youth through the youth of these things.

__________________________________

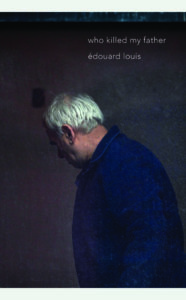

Excerpted from Who Killed My Father by Edouard Louis, translated by Lorin Stein, forthcoming from New Directions Publishing.

Edouard Louis

Born Eddy Bellegueule in Hallencourt, France, in 1992, Édouard Louis is a novelist and the editor of a scholarly work on the social scientist Pierre Bourdieu. His third book, Who Killed My Father, is out now from New Directions.