On Stella Nyanzi's Fearless Political Poetry

Prison Writing in the Social Media Age

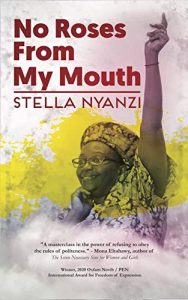

The poet and academic Stella Nyanzi was released from prison in February 2020, weeks after the publication of her poetry collection, No Roses From My Mouth. The following is taken from the book’s introduction.

*

In Carole Boyce Davies’ study of the political activism of the Black Communist, Claudia Jones, Davies writes that “[Jones’] was a poetry written by an activist who uses the space of incarceration and the time of detention to reflect on the conditions of being incarcerated itself, the political conditions of the state, and on the nature of the human condition.”

Stella Nyanzi’s No Roses From My Mouth includes 158 poems written in 2019 and 2020 from Luzira Women’s Prison in Kampala, Uganda during a trial and serving time for cyber-harassing and offending the President of Uganda, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, in a poem where she uses his dead mother’s vagina as an image to comment on her son’s “oppression, suppression and repression” of Ugandans. This poetry collection, like Claudia Jones’ poetry, includes poems “written by an activist who uses the space of incarceration and the time of detention to reflect on the conditions of being incarcerated itself”, the position of the woman in society, and the political conditions of the Ugandan state.

Within academic and LGBTIQAP+ activist circles, Stella Nyanzi is more renowned for her stellar scholarship on sexualities as a medical anthropologist and is a leading authority in African Queer Studies, or Queer African Studies. In April 2016, when she staged a naked protest against the director of the Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR), Nyanzi located herself within a tradition of radical African protest that utilizes the body and custom to condemn injustice and oppression. Her naked protest at MISR premises was live-streamed on her Facebook page, showing the centrality of the social media platform to Nyanzi’s activism.

In 2017, Nyanzi criticised Museveni, his wife, and their family for reneging on a campaign promise to provide sanitary pads to menstruating girls so that they could remain in school. When she was summoned to the police to answer questions about her Facebook criticism of the government, she launched a campaign: #Pads4GirlsUg. She was banned from traveling while under investigation, but no one can stop Nyanzi.

She went to schools and taught girls about menstruation. She sang them educational songs about menstruation. She talked to various people and raised money and pads to distribute. She went to many parts of the country with the campaign. Then the Kampala Metropolitan Rotary Club invited her to speak to them about the campaign. She went. And she was arrested that Friday night. She was betrayed. Her comrades online and offline started the #FreeStellaNyanzi campaign right away.

Stella Nyanzi carried empty coffins to protest. She was arrested, with her comrades too many times, her car vandalized as she protested.

When she was presented in court, the prosecution didn’t charge her for hurting the President’s wife’s feelings as was expected. They picked another Facebook post in which she described Museveni’s speech celebrating so many years of staying in power, in which he said that he is not anybody’s servant, as Lutako. Lutako as the language of matako. Lutako as the jiggling of buttocks.

Nyanzi called Museveni a pair of buttocks. It made for punny headlines worldover. Online and other activists agitated for her release. It came after 33 days. She received bail, as the trial couldn’t continue because the prosecution had wanted to subject her to a compulsory mental health examination and she petitioned the constitutional court to challenge the law under which they were proceeding.

Once free, Nyanzi picked up the struggle from where she had left it, when she recovered after the 33 day jail stint. Nyanzi’s Facebook timeline brims with commentary and language that brings meaning for many lives. Nyanzi is the voice of many. Her Facebook is the voice of many. She speaks for so many, and eloquently. She shows up for many causes.

Her work in the period she has spent on suspension from Makerere University, imposed over her naked protest and subsequent criticism of Museveni’s wife has been unsalaried activism online and offline. Nyanzi has been a fulltime liberation worker since 2016, applying her creativity, her training, her knowledge and connections to the cause of freedom in Uganda. Mr. Museveni, his wife, and their handlers fear Nyanzi’s Facebook timeline. They don’t want her Facebooking.

In 2018, the spate of killings and kidnappings of women in Uganda didn’t escape Nyanzi’s eye and heart for freedom and justice. She convened a Women’s Protest Working Group to address the involvement or mishandling of the killings and kidnappings of women by Museveni’s military government. She carried empty coffins to protest. She was arrested, with her comrades too many times, her car vandalized as she protested. She called for a one million march to protest the killings and kidnappings.

The police shockingly cooperated at the last minute despite suggesting that they would foil the planned march. Over 300 people, some from outside countries, including ambassadors of foreign countries, sex workers, relatives of deceased women, professional activists from NGOs, political activists, journalists, LGBTIQAP+ activists and private individuals, students, etc. showed up for the march. Nyanzi is a force. She is the embodiment of a political resistance movement in a social media era.

When the musician turned opposition politician Robert Kyagulanyi (alias Bobi Wine) was brutally arrested in Arua, with fellow Members of Parliament Zaake Francis, Karuhanga Gerald, and others, the parliamentary candidate who eventually won the bi-election, Kassiano Wadri, the local woman politician Night Asaro and others, Nyanzi was there to mobilize support for them.

That was around mid September of 2018, the time Museveni chose for his birthday whose exact date he says, nobody knows. Nyanzi had an idea. She wrote a poem to celebrate Museveni’s birthday. Life continued. Hell didn’t break loose. The heavens didn’t fall. But Museveni and his handlers’ feelings were hurt. Nyanzi continued with her life, her commentary, with her online and offline activism.

On November 2nd, 2018, she went to the police to get security to accompany her as she peacefully marched to her office at Makerere since the university staff tribunal had cleared her of all charges and ordered her reinstatement. It was not to be. The police arrested her. The second round of the #FreeStellaNyanzi campaign started. When they presented her in court, they charged her with cyber harassing and offending Museveni and his dead mother in the birthday poem for referring to the vagina from which Museveni was born. She has been in jail since November 2nd, 2018 to the date of publishing this collection.

To publish prison literature while the political prisoner is still in jail is to hide in plain sight.

The first batch of the poems was released on her 45th birthday on June 16th, 2019 celebrated while she was in jail. Various comrades living in various countries shared the poems on their Facebook, Twitter and Instagram timelines and pages among other social media platforms under the hashtag #45Poems4Freedom. Some of them already appear on some blogs.

To borrow Frantz Fanon’s formulation, Nyanzi is resolutely a poet of her time. The context in which these poems were written, the context in which these poems are being published must be brought front and center in reading and discussing them. We recognize that Nyanzi is not the first writer to produce work under prison conditions. Next door in Kenya, Ngugi Wa Thiongó wrote the novel Caitaani Mutharaba-ini (Devil on the Cross) on toilet paper in his prison cell.

He was jailed for the play he had co-written with Ngugi wa Miiri about the continued exploitation and oppression of native peasants by Western monopoly capital in cohorts with native elites. His memoir of the prison experience, Detained (new edition Wrestling with the Devil) was written and published once he was released. The Black Communist activist and organizer Claudia Jones wrote poetry while in jail. Some of it appears in the posthumously published collection titled Beyond Containment, bringing together various essays, speeches, and poems by the activist.

Other writers who have been imprisoned for their writing and activism and indeed continued to write while in jail include the Ogoni writer and environmental rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nobel Prize for Literature Winner Wole Soyinka, and the Egyptian writer Nawal El-Saadawi. The Malawian Jack Mapanje was jailed for writing critically about the Kamuzu Banda regime in Malawi. The South African, Caesarina Kona Makhoere writes about her experience in jail during the apartheid era.

Nyanzi is not only one of the many writers jailed for the political nature of their work, but she also belongs to the class of prison-writers who, despite the fact of imprisonment, continue to write behind bars.

The conditions of the prison affect one’s writing while in prison. Some of Nyanzi’s poetry was confiscated and so has not made it to this collection. The prison censorious eye that forced Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci to omit the name of Marx and the word “class” in his famous prison notebooks is still a reality for prison literature in the social media era.

To publish prison literature while the political prisoner is still in jail is to hide in plain sight. It is to pose a risk of “disciplinary” sanction against the prisoner. It is to raise a big middle finger to the system of repression, oppression and suppression. It is to declare that our minds are free, our imaginations are free from the prison warder, the prison walls, and the judges’ sentence.

__________________________________

From the introduction to No Roses From My Mouth by Stella Nyanzi. Used with the permission of the publisher, Ubuntu Reading Group. Introduction copyright © 2020 by Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire and Esther Mirembe.

Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire and Esther Mirembe

Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire is an academic, activist, lawyer, organiser, publisher, and writer. He cofounded the Centre for African Cultural Excellence which runs various projects including Nyanja Football Club, Abateebana Cultural Troupe, Ubuntu Reading Group, the Arts Managers and Literary Activists (AMLA) Network, and the Writivism Literary Initiative.

Esther Mirembe is a writer. They are the Managing Editor of Writivism, and a 2020 Centre for Art, Design and Social Research fellow.