On Stealing Time to Make Art in an Overcrowded Life

Jackie Morris, the Artist and Author Behind The Unwinding, Breaks Down Her Process

There’s a tension that builds during the making of a book, almost like the winding of a cog, tighter and tighter. In my case, that tension was in the balance between living and working, deadlines and meetings. During that time, certain daydreams entered my head and wouldn’t let go until they were granted physical form in pigment and water.

As a child I was told art was a hobby, not a profession; I was admonished regularly for drawing and dreaming. As an adult I was told that it was impossible to work and be a parent, but I have a hunger to create, and the drive to find ways to make things work, and a ceaseless desire to paint, and a fear of how my mental health would deteriorate if I could not, at all times, create.

Luckily, I was reasonably established at my craft when my children were born, but then I needed to learn how to work around the demands and needs of children. While my children were still young, my marriage disintegrated, and I became a single parent. Rising early to work before they were awake, staying up late to work while they were asleep; these were ways I found my own space to create. Once they could read it was easier. Distract them with books! I always said I raised them on a regime of benign neglect and they soon learned how to fend for themselves.

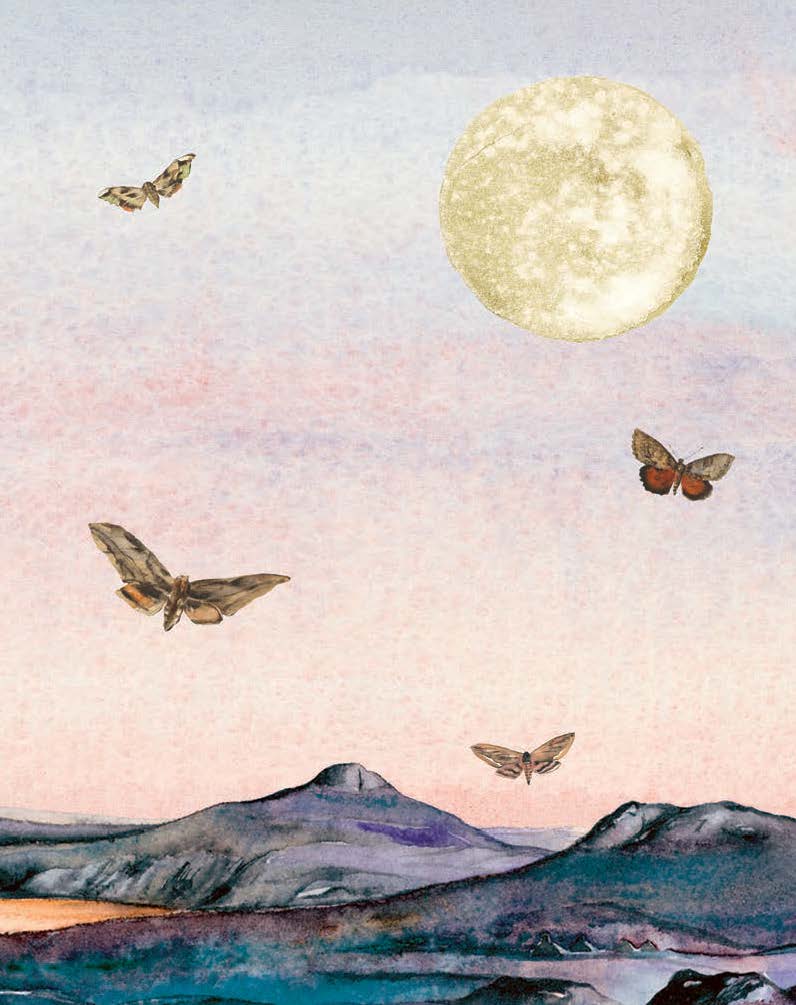

Image from The Unwinding: And Other Dreamings, written and illustrated by Jackie Morris.

Image from The Unwinding: And Other Dreamings, written and illustrated by Jackie Morris.

It was never that my work lived in the margins of my time around raising a family; I think, rather, that I learned how to entwine life and work so that each informs the other. As my children grew, bedtime stories became research for me as well as the most beautiful time of the day, sharing stories and art. During the day I could sketch the children as they played—they were beautiful models for constant life drawing. Even better, when they were asleep. If you can tangle your life so completely in your work, there are no edges (though my accountant wouldn’t accept my suggestion that my children should be work-related tax-deductible expenses because so much of my time with them was helpful for research).

Now I have new lessons to learn, unanticipated ones, including the need to work around the requirements of aging parents. My father was taken very ill at the beginning of 2020. During his last weeks, I worked on the glossary images for The Lost Spells. These small paintings were my relief from what was happening. He died just before lockdown, peacefully. I carried my grief for him through into my work, onto the wings of the owl that carries the key on the cover of The Lost Spells.

The same attention to detail one gives to one’s work should be applied to all aspects of life.

The desire to spin these together into a book for dreamers began as a wish to make a book that could be a harbor for people. It seemed the world was so tense. So many people I knew were turning to medication to help them through their days. I wondered if I could use my own stress relief to make a book that would work as a medicine for others.

The book was originally called The Space Between, because the artwork, and the stories, were being made in those spaces between creativity and family life. Then it became The Keeper of Lost Dreams. And in a conversation, as I tried to pass on my vision of how this book would work, to Alison O’Toole—who designed the book and did so much more—The Space Between became The Unwinding.

Time is so precious. As authors we are making a barter, a bargain with our readers. We ask for your attention, your time. In return, what I have tried to offer with The Unwinding is a place to rest, a distraction from the constant bombardment of bad news. So few images. No more than twenty, maybe. Such a slight text. Small enough to carry with you should you need to use it as a shield during the day, a talisman to be tucked under a pillow at night. I wanted the book to have a weight about it and space for the reader—to step into, to breathe through.

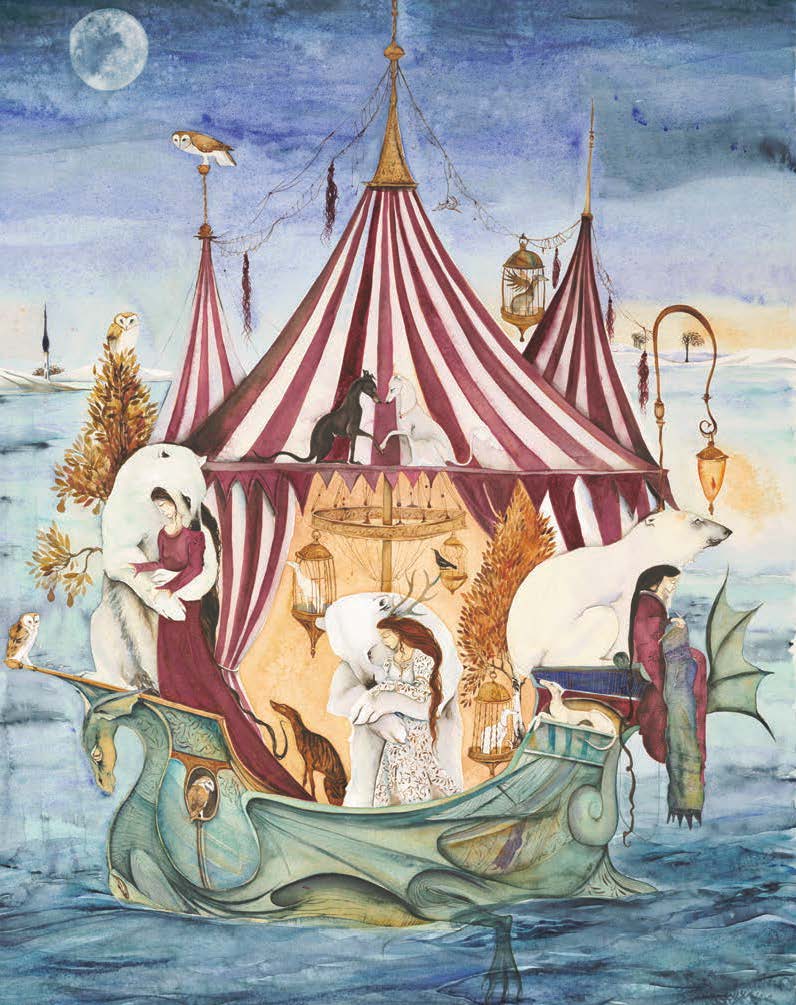

Image from The Unwinding: And Other Dreamings, written and illustrated by Jackie Morris.

Image from The Unwinding: And Other Dreamings, written and illustrated by Jackie Morris.

Alison took my simple introduction and turned it into an apothecary poster: she wove together images to create a flow of dreams, framing and fading; a forest here, a detail there, rich but also filled with space. (Alison has a small child also, and worked late into the night while he slept, in order to meet the deadlines. She lives in Australia. Meetings were always at twilight: hers or mine.)

*

As I get older, I remember something the British painter Stanley Spencer said: that the same attention to detail one gives to one’s work should be applied to all aspects of life. During the war, Spencer, a pacifist, worked in field hospitals. As he cleaned hospitals, worked in the trenches, treating the wounded, all the while he drew.

Each day I try to understand and practice this a little better. It takes time and patience. It is an intense way to live. But it heightens the dreaming and magically slows down time: paying attention allows me to dream wider and more wildly. And I understand that this is what I request from my readers: that time be given to read the images as much as the words.

Image from The Unwinding: And Other Dreamings, written and illustrated by Jackie Morris.

Image from The Unwinding: And Other Dreamings, written and illustrated by Jackie Morris.

Innovation requires clearing one’s mind of how things should be done, or have always been done, and opening it to dreaming. This is the fertile ground in which new ways of being will grow, and new paths will appear—or those hidden beneath the noise of the everyday will reveal themselves. Dreaming is not passive; it is the most active thing you can do. Continuing with the status quo is passive. We no longer have the luxury to do this.

My hope for The Unwinding is that it will become a harbor for its readers and a catalyst for creativity; that it will still some of the cacophony of modern life, trim the doubts and the despair to the wick, and give space to reignite hope in dreams. I want it to be a light in the darkness. Creativity is the antidote to despair and we are a creative species, if we allow ourselves the time to be.

__________________________________

The Unwinding by Jackie Morris is available via Unbound.

Jackie Morris

Jackie Morris is an author and illustrator. She studied illustration at Hereford College of Art and Bath Academy and has illustrated many books, and written some. The Lost Words, co-authored with Robert Macfarlane, won the Kate Greenaway Medal 2019. Her newest title, The Unwinding: And Other Dreamings, is out from Unbound in November 2021. @JackieMorrisArt