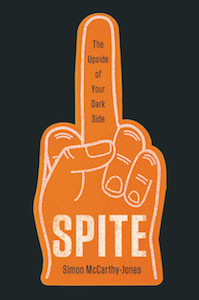

On Spite: The Pros and Cons of Being Deeply... Petty

Simon McCarthy-Jones Offers a Brief History of

Small Human Vengeances

Spite runs deep. We find it in our oldest stories. It is there in the myths of ancient Greece. Medea kills her children, just to spite her unfaithful husband, Jason. Achilles refuses to help his Greek comrades fight because one of them has stolen his slave. Folklore tells of spite. A magical being offers to grant a man one wish. Naturally, there is a catch. Whatever he gets, his hated neighbor will get double. The man wishes to be blind in one eye. Such stories, although buried in time, still speak of an instantly recognizable behavior.

Today, we know that spite can be petty. A driver lingers in a parking space, just to make you wait. A neighbor puts up a fence, solely to block your view. We may also realize how damaging spite can be. A spouse seeks custody of a child, just to get back at their ex. A voter supports a candidate they hope will cause chaos. But are we prepared to recognize that spite may have a positive side?

What exactly is spite? According to the American psychologist David Marcus, a spiteful act is one where you harm another person and harm yourself in the process. This is a “strong” definition of spite. In weaker definitions, spite is harming another while only risking harm to yourself. It can also be harming another while not personally benefiting from doing so. Yet, as Marcus points out, a strong definition of spite, in which harming another entails a personal cost, helps differentiate it from other hostile or sadistic behaviors.

Indeed, a helpful way to understand spite is to look at what it isn’t. When we consider the costs and benefits of our actions, there are four basic ways we can interact with another person. Two behaviors involve direct perks for us. We can act in a way that benefits both ourselves and the other (cooperation) or in a way that benefits ourselves but not the other (selfishness). A third behavior involves a cost to us but a benefit to the other. This is altruism. Researchers have dedicated lifetimes to the study of cooperation, selfishness, and altruism. But there is a fourth behavior, spite. Here we behave in a way that harms both ourselves and the other. This behavior has been left in the shadows, which is not a safe place for it to be. We need to shine a light on spite.

Spite is challenging to explain. It seems to present an evolutionary puzzle. Why would natural selection not have weeded out a behavior in which everybody loses? Spite should never have survived. If your spite benefits you in the long run, then its continued existence becomes comprehensible. But what about spiteful acts that don’t give you long-term benefits? How can we explain those? Do such acts even exist?

Spite also poses a problem for economists. What kind of person acts against their self-interest? For the longest time, economists didn’t think there was a problem to explain. The famous 18th-century economist Adam Smith claimed that people were “not very frequently under the influence” of spite, and that even if it did occur we would be “restrained by prudential considerations.”

Much later, in the 1970s, the American economist Gordon Tullock claimed that the average human was about 95 percent selfish. In the “greed is good” era of the 1980s, many may have believed that this estimate was on the low side.

Economists viewed humans as a creature called Homoeconomicus—a being that acted rationally to maximize its self-interest. Self-interest was typically, though not always, understood in financial terms. Yet, as I will discuss in Chapter One, back in 1977 a groundbreaking study found that people were often quite happy to turn down free money. Adam Smith had been overoptimistic. Something very real and very powerful lurked in Tullock’s residual percentage.

Spite involves harm, but what constitutes harm? Who gets to decide whether an act is harmful and thereby has the power to define an act as spiteful? To take an extreme example, does a suicide bomber, who thinks they will be rewarded in the next life and their family compensated in this life, harm themselves or not?

Evolutionary biologists possess an objective measure of harm: a loss of fitness (reproductive success). We will look at spiteful acts involving a loss of personal fitness, so-called evolutionary spite, in Chapter Four. In contrast, economists and psychologists tend to focus on harm in the form of immediate personal costs. This “psychological spite” can turn out to have unforeseen long-term personal benefits. Such spite ages well, maturing into selfishness.

Once we are happy with our definition of spite, two questions remain. First, what drives someone to act spitefully in the moment? That is, how does spite work? This is spite’s proximate explanation. Second, what is the deeper reason we are spiteful? Why does spite exist? What is its evolutionary function? This is the ultimate explanation of spite. To take an example from another area: why do babies cry? The proximate explanation may be cold or hunger, but the ultimate explanation is to get care from its parents. What are the equivalent answers for spite?

Are we prepared to recognize that spite may have a positive side?

When we have an ultimate explanation of spite, we can begin to consider the pressing question of how spite shapes the modern world. A love of sugar and fat helped our ancestors, pushing them to eat high-energy foods. Yet in the Western world today, where cheap sugary and fatty foods are ubiquitous, what was once adaptive now causes diabetes and heart disease. What happens when our evolved spiteful side runs into a world it was never meant to deal with? What are the effects of spite in a world with levels of economic inequality, perceived injustice, and social media–enabled communication that would be utterly alien to our ancestors?

The problem is pressing because spite seems more than dangerous. From some angles it looks like human kryptonite. Spite is, by definition, the exact opposite of cooperation, which is worrying, because cooperation is our species’ superpower. Our success as a species has come from our remarkable ability to work together. Although even slime molds cooperate, we turn cooperation up to 11. This allows us to live in large groups with nonrelatives, something that our less cooperative primate cousins cannot do.

Our ability to cooperate at scale keeps us safe from a Planet of the Apes–style takeover for the time being, yet there are many other things to worry about short of primate overlords. If spite damages cooperation, it would not only hamper human progress; it could also reduce our ability to solve the complex global problems we face. The world is getting better, but progress is not guaranteed.

Spite can also be terrifying. Is there anything more frightening than an adversary unfettered by the bonds of self-interest? Selfishness can be a problem. But at least we can reason with a selfish person’s self-interest. What do you say to a spiteful person who values your suffering more than their own well-being? They are like a Terminator. They can’t be bargained with, can’t be reasoned with, and absolutely will not stop, ever, until you are, if not dead, at least inconvenienced. Unfortunately, such creatures are not limited to science fiction.

Late in the Second World War, Germany’s fight against Russia was intensifying. Hitler had to balance using trains to transport Jews to their death in the east against using the same trains to carry vital weapons, fuel, and supplies to his army fighting the Russians. Hitler chose Holocaust. He was prepared to risk the destruction of Germany to eliminate the Jewish people. The horror of spite has no bounds.

Spite poses clear and horrific dangers. We need to understand it in order to control it. To do this, we are forced to look closely at spite. And when we do, something else emerges. What we find forces us to reconsider whether we may have misunderstood spite. The American philosopher John Rawls argued that moral virtues are character traits that we should rationally want other people to have. Spite, he claimed, is not something we should want others to have, and therefore it is a vice that is “to everyone’s detriment.” But is it?

It turns out that spite can be a force for good. It can help us excel. It can help us create. And it does not necessarily threaten cooperation. In fact, paradoxically, it may spur it. Spite does not inevitably produce injustice. In fact, it may be one of our most powerful tools for preventing it. As long as injustice and inequitable inequality persist, we may need spite.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Spite: The Upside of Your Dark Side by Simon McCarthy-Jones. Copyright © 2021. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of HBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Simon McCarthy-Jones

Simon McCarthy-Jones is associate professor of psychology at Trinity College Dublin. His research has appeared in Nature Communications, Clinical Psychology Review, and elsewhere. He has been featured in Newsweek and New Scientist and on BBC News, ABC Radio, and the BBC World Service. He lives in Dublin, Ireland.