On Slaughterhouse-Five, the “Ultimate PTSD Novel”

Tom Roston Considers the Ongoing Popularity of Kurt Vonnegut’s Classic

“Rereading Slaughterhouse-Five taught me two things about the novel: how great it really is, and what it’s really about. It’s not about time travel and flying saucers, it’s about PTSD,” wrote William Deresiewicz, an author and critic, in The Nation magazine in 2012.

Readers have been looking at the book through the psychological trauma prism since the novel first came out. In 1974, literary critic Arnold Edelstein wrote, “‘So it goes’ . . . is earned at a price terrible enough to be psychologically consistent with the horror of Billy’s experiences. The only way he can live with his memories of his past and his fear of the future and find meaning in both is to withdraw from reality into a pleasant but neurotic fantasy.”

In 2019, writer Salman Rushdie gave a talk commemorating the 50th anniversary of the novel and said, “It is perfectly possible, perhaps even sensible, to read Billy Pilgrim’s entire Tralfamadorian experience as a fantastic, traumatic disorder brought about by his wartime experiences—as ‘not real.’ Vonnegut leaves that question open, as a good writer should. That openness is the space in which the reader is allowed to make up his or her own mind.”

The 50th anniversary, which was celebrated with the launch of a special hardcover edition and a series of appreciations in the media, was a moment to reflect on the significance of the book. The New York Times framed the novel as “a self-help manual for psychic pain at a time when many young Americans needed it most.” Fifty years ago, the Vietnam War was cleaving at the American soul. The plight of the nearly three million veterans who fought it helped define that era. Today, the same number of men and women, 2.7 million, have served in recent conflicts in the Middle East. And with the COVID-19 pandemic killing hundreds of thousands of Americans and upending all our lives, we are going to need as many self-help manuals for psychic pain as we can get.

Approximately 125,000 copies of Slaughterhouse-Five were sold in 2019. Across the country people were giving it a first, second, or tenth read. And those sales didn’t represent a spike because of the anniversary; throughout the 21st century so far, about that same number of copies have been sold every year. It’s impossible to track, but those numbers must be dwarfed by the dog-eared, used copies of the book that are lent, borrowed, and stealthily lifted from living room shelves or sold through secondhand bookstores.

Throughout the 21st century, about 125,000 copies of Slaughterhouse-Five have been sold every year.

I spoke with Steve Almond, bestselling author (Candyfreak, Against Football), writing professor, and Vonnegut devotee, about why he thinks the book’s readership remains strong. But first, a couple notes about Almond: When I say he’s a devotee, I should be more clear. Vonnegut is in a league of his own in inspiring years and years of obsessive fans who have read all of his books, quote from them until their friends want to throttle them, and litter their yearbook pages with his wisdom. Almond was once one of those fans. Perhaps you were as well. Almond says he read most of Vonnegut’s novels more than six times, in addition to almost everything else he wrote, including his speeches.

Another thing about Almond: I have a distant connection to him and someone I know once pointedly referred to him as a successful writer, making me feel about two feet tall. So, I approached him with mixed feelings of awe, envy, and respect. And a wee dram of hostility.

Almond wrote his college thesis on Vonnegut and he almost wrote a biography of him but instead published a seventeen- thousand-word essay titled “Everything Was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt,” which he included in his 2007 collection (Not That You Asked): Rants, Exploits and Obsessions. In it, Almond astutely writes of Vonnegut: “The evidence was in his books, which performed the greatest feat of alchemy known to man: the conversion of grief into laughter by means of courageous imagination. Like any decent parent, he had made the astonishing sorrow of the examined life bearable.”

It’s a fantastic piece of writing. Almond explains how Vonnegut inspired him to become a writer and helped him endure his own “family beset with sorrow.” So, yes, Almond knows of what he speaks when he tells me that fundamental to Slaughterhouse-Five’s appeal is that fans seamlessly identify with both the protagonist and his creator because it feels like nonfiction. “This is what it feels to be me,” Almond says of the Vonnegut reader. “This is not just a writer pulling something out of his bag of tricks. He understands me. And it’s a byproduct of his traumatic history.”

The Times article recognized the war trauma of the main character, Billy Pilgrim, which was nothing new. That’s been done in countless classrooms, reviews, and dissertation papers. In the book, Pilgrim stumbles between states of catatonia, crying jags, and childlike befuddlement. He also becomes “unstuck in time” and travels to the faraway planet of Tralfamadore, which can be interpreted as actually happening in the narrative or as only occurring in Pilgrim’s mind as a symptom of his trauma.

But the Billy-Pilgrim-has-PTSD understanding of the book has more recently budded an interpretation that the trauma of the character also mirrors the author’s own. In that New York Times article, Kurt’s daughter Nanette said her father experienced PTSD and that “he was writing to save his own life . . . and in doing it I think he has saved a lot of lives,” meaning that both her father and his readers found healing in Slaughterhouse-Five. I imagine reducing his book to a clinical diagnosis or, perhaps worse, putting it in the self-help category, would make Vonnegut shudder.

Vonnegut didn’t touch the collective American psyche with a medical text or an anti-war manifesto but with a story spun from his creativity.

In a series of conversations, Klinkowitz, who began writing about Vonnegut in the early 1970s, pushed back on my interest in the PTSD connection to Slaughterhouse-Five. “When Kurt wants to make a literary character, he is not writing a psychological study,” he says. “He is crafting a work of art. In the book he is creating how the world looks to Billy. And it turns out that’s how the world looks to most of us. You can learn all you want by talking to psychiatrists but to find out how a character reacts to trauma, you have to create an imaginary construct.”

I agree. Vonnegut didn’t touch the collective American psyche with a medical text or an anti-war manifesto but with a story spun from his creativity. Although his son, Mark, believes that his father had PTSD and that “you find with combat PTSD that it helps people survive to tell their narrative,” he dismisses the notion that his father wrote Slaughterhouse-Five with a clear purpose or target. “He was incredibly intuitive. I don’t think he had a theory or a strategy,” Mark says. “He knew when he had something right but I don’t think he could have told you how to get there. And he had no clue what people would think of it.”

As it turns out, the book has become what Iraq War veteran Kevin Powers calls a “touchstone” in many peoples’ lives, especially that of veterans. Powers, who wrote the foreword to Slaughterhouse-Five’s 50th anniversary edition, refers to one of his most harrowing war experiences—he was on a rooftop staring through a 4x scope on his M240B machine gun when his fellow soldiers shot and killed an elderly couple who waved a white flag from their car—as his “moment trapped in amber,” a moment that remains frozen in his mind, a reference to the Tralfamadorian concept of time and free will.

Powers told me that he drew the jumping-back-and-forth structure of his novel, The Yellow Birds, a National Book Award finalist, from Slaughterhouse-Five. He relates to being unstuck in time and sees its function in Vonnegut’s novel “as this miraculous, perfect device that can represent the trauma response that a lot of veterans have.”

“I would argue that this book is among the most humane works of art ever created. It is concerned with and dedicated to the alleviation and prevention of human suffering in the face of its inevitability, and I can think of no braver moral position to take than that one,” Powers wrote in his foreword. “You can have Job. I’ll throw in my lot with Billy Pilgrim.”

Alex Horton, an army infantryman in 2007, carried Slaughterhouse-Five to his guard posts in Baghdad and to stations in the Diyala River valley, where he shared it with other soldiers. The book was like a “talisman” for Horton, who could not have then articulated why it was so meaningful to him but later came to realize that the book demonstrated that “this thing that is happening to you right now, these days, will be just as important to you twenty years from now or when you’re 80 years old,” Horton says. “These things are going to spiral through your life and they are going to attain different meaning as you grow older.” When he got back from Iraq, Horton’s feelings of hurt and regret were mitigated by Vonnegut’s story, which he turned to for “solace.” Horton says that the book was essentially “a blueprint on how to get from Billy Pilgrim to Kurt Vonnegut.” And although he didn’t specifically try the novelist’s path, the Texas-born veteran became a successful Washington Post staff writer, covering mostly military matters, committed to the “daily reporting grind.” Without such a blueprint, the imprint of war can often be overwhelming.

Many veterans are unable to assimilate their memories of their deployment. Indeed, a lifetime of wrestling with PTSD symptoms has plagued this new generation of soldiers engaged in the “endless wars” of the Middle East. About one in four soldiers has or has had mental health issues. Since the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders designation of the diagnosis in 1980, there’s been increasing awareness and understanding of the ravages of wartime PTSD, a national tragedy that hasn’t diminished despite decreased engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan. A total of 6,435 US veterans killed themselves in 2018. And the increase of suicides over the past decade by younger vets, aged 18 to 35, has been significantly higher than that of non-veterans. It’s shocking: Veterans kill themselves at a rate that is two times higher than that of all Americans.

But the legitimacy and growing acceptance of combat PTSD has been tarnished and subsumed by the twin veils of popularization and skepticism. Several factors have contributed to the weakening of the validity of the PTSD diagnosis. It doesn’t help that its defining characteristics include that it can be fluid, multifaceted, and lacking in physical properties (although improved brain scans are beginning to reveal more of how PTSD can directly impact neurons).

In the 21st century, it feels like anyone can get it. And so, conversely, it seems like no one has it. PTSD has transformed from being a clinical diagnosis to a grab-all description of past pain. I just stepped away from writing these very words and listened to a podcast in which a pundit and a journalist bemoaned their shared “PTSD” from the 2016 election victory of President Trump. The term has become shorthand for anything distressing. When singer Alanis Morissette or actor Keira Knightley claims to have PTSD from the detrimental effects of fame, or actor Shia LaBeouf says he has PTSD from past familial suffering to help explain his bad behavior, however legitimate their pain may be, it dilutes the diagnosis. Furthermore, in a litigious, me-first society, claiming PTSD can translate into financial rewards, which further complicates our understanding of it.

The National Institute of Mental Health ranks PTSD as the third most common mental illness in the United States. In any given year, there are eight million people who suffer from it. Whether or not these numbers are real, inflated, or suppressed almost doesn’t matter anymore. This millennium began with the trauma of the September 11 attacks, wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, mass shootings, climate-change-fueled natural disasters, and now COVID-19. Trauma has come to define us as a nation.

Of course, it would be fatuous to suggest our pains are all we are or that they supersede that of previous eras. Without even getting into the genocide of Native Americans and the scourge of slavery, there have always been wars, hard times, and the ravages of disease. But what differs now is that previous generations of the modern era experienced trauma and then, rightly or wrongly, moved on. It was almost like a collective amnesia. Each major war of the 20th century introduced Americans to the affliction of war trauma anew. Today, PTSD, in its accurate and conflated form, overused or blindly rejected, looks to be settling over us like a permanent haze.

But Vonnegut provided us with a beacon that has time-traveled, unscathed, from the past. The author’s two-decade struggle to write a book that depicts the trauma of war truthfully, without cheapening it, anticipated the PTSD diagnosis. “Slaughterhouse-Five is the ultimate PTSD novel,” says Duke University professor and psychiatrist Harold Kudler, who was the chief consultant for mental health for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from 2014 to 2018. “It is a fully rendered metaphorical exploration of what it means to be ripped out of your own person, relationships, place and time written by a man who had actually experienced this.”

And even more, his story of fractured identity and trips in time and space provides a navigational tool. Billy Pilgrim is a war veteran unlike any other and yet he is universal. Vonnegut circumvented conventions, labels, and false sentiments. He blew all of that up, and by doing so he put a wedge in readers’ resistance to ambiguity and complexity. Vonnegut’s book, and the way he lived his life, tell us an entirely original story about what it means to be human.

_______________________________________

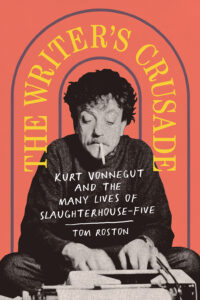

Excerpted from The Writer’s Crusade by Tom Roston. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Abrams Books. Copyright © 2021 by Tom Roston.

Tom Roston

A journalist for over 20 years, Tom Roston worked at The Nation and Vanity Fair, and was a senior editor at Premiere for a decade. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Fast Company, New York Magazine, Food Republic, Salon, and more. He lives in Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of The Most Spectacular Restaurant in the World.