On Shapes of Native Nonfiction and the Story Form of

Native Basketry

Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton, with Meranda Owens, at the Field Museum of Natural History

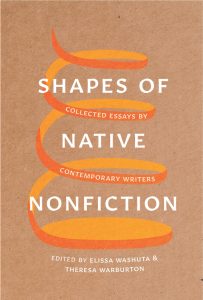

One year ago, our co-edited book Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers was published by University of Washington Press. Since taking material shape, the book, though unchanging as an object, has grown and shifted as a piece of conversations in classrooms, libraries, and other spaces. In August 2019, we (the editors) presented a joint talk at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. The collection’s introductory framing of these form-conscious essays brings basket weaving craft into a discussion of the purposeful relationship between form and content. We were invited to the Field by Meranda Owens, PhD, currently the Postdoctoral Research Scientist in the Native American Exhibit Hall. Meranda shared this statement about the context for our visit:

Meranda Owens: In June 2018, I began working at the Field Museum of Natural History as a post-doctoral researcher for the North Native American Hall renovation. Eventually, I was recruited to curate my own section of the hall that is based off of my dissertation work regarding the way Native women use basket weaving as a way to uphold ancestral teachings and personal agency. As I discussed this opportunity with a colleague from the University of Washington Press, she quickly brought up the work Theresa and Elissa had just completed through their anthology, Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers. We soon connected and began discussing the benefit of having them present their work at the museum.

The Field Museum’s relationship with Native American communities has often been strained due to a lack of thorough collaboration and willingness to admit its problematic past. For the most part, Native people do not come to the museum in the hopes of seeing an accurate portrayal of themselves and their histories. Accordingly, the renovation of Native hall, as well as the hiring of Native staff has been one way that the museum has begun to initiate positive change. In my position, I have worked on having more Native people connect with the museum’s collection of Native American items, so that the public can understand the importance this interaction has in healing past traumas and in connecting to ancestors that have been stored away for too long. This need to have collections be more accessible to Native audiences is what drove my desire to have Theresa and Elissa present their anthology in the presence of baskets collected by Field Museum anthropologists in the early 1900s.

As is so eloquently illustrated in Shapes of Native Nonfiction, baskets are a way to transmit important information about a community’s practices, language, and spirituality. Like the prose of a poem or the organization of an essay, the construction of a basket takes practice and time. Nevertheless, when a piece is finished it is filled with beauty, strength, and honor. When we examine writing in the same way we examine a basket, we can appreciate the admiration one has in communicating messages to loved ones or peers. Though I was not able to attend the event due last-minute travel, I heard that the way Theresa and Elissa styled their discussion honored their admiration for prose and the beauty of Native basketry.

*

Debra Yepa-Pappan, Community Outreach Engagement Coordinator, served as our host for the event. She and Meranda facilitated the display of several baskets during the reading: we shared space at the front of the room with Paiute and Pomo baskets, some so tiny the woven strands were nearly impossible to see. We were honored by the trust our hosts put in us. Having the opportunity to be in that space, to speak in a place filled with stories and with material objects that carry those stories, was overwhelming, and we tried to live up to the responsibility of being in relation to those stories, those objects, and their communities. We have reshaped our scripted spoken remarks to fit this textual space offered by Literary Hub.

Elissa Washuta: In 2013, while living in Coast Salish territory, I traveled with a group from the University of Washington to the Port Madison Indian Reservation, home to the Suquamish Tribe. We were invited guests at the home of Ed Carriere, a Suquamish elder and master basket-maker. He learned old-style split cedar root basket-making from his great-grandmother, and he had filled his home with baskets. Some were his replicas of old baskets made from his study of woven fragments from sites where artifacts were preserved for thousands of years before exposure by river erosion. Most, though, he’d made using techniques maintained into the present through a lineage of Suquamish weavers.

The baskets were remarkable, but there was one I thought about the most in the years that followed, one I most wanted to hold again when I returned to Ed’s house four years later. Ed spent a thousand hours making the basket, and it told the story of his life. Listening to him talk about his craft and show us how he worked, and doing this listening while on the land where his people have lived since the beginning of time, has had a profound effect on my own relationship with craft and cosmology. Materials, methods, land, and time converged.

When we examine writing in the same way we examine a basket, we can appreciate the admiration one has in communicating messages to loved ones or peers.

I’m a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and also come from Columbia River people; my formal creative writing education took place at American research universities. Text-based craft lessons were disconnected from place and time. Our classrooms, too, seemed placeless, and discussions were stuffed into blocks of time whose boundaries sometimes impinged on our ideas’ expansiveness. At Ed’s house, things took the time they took: we passed around baskets and held them as long as we needed to; he showed us his methods and explained how he weaved; we all ate lunch out by the sound together, and when we were done, we departed.

In writing nonfiction, my greatest fascination is with form, and with the relationship between form and content that determines structure. Form is the visual shape of a text: the paragraphs, the stanzas, the space. Non-Native narrative theorist Caroline Levine writes, “Every literary form … generates its own separate logic.” Because ways of reasoning emerge from an essay’s shape, form cannot be uncoupled from what the essayist seeks to understand. But in so many representations of Native lives and histories, that uncoupling has happened as relationships between stories and people have been broken by opportunistic ethnographers, appropriative artists, and exploitative documentarians, all of whom might have their audiences thinking Native people are nothing but our pain.

In our introduction to the collection, Theresa and I wrote,

We conceive of the essay as an exquisite vessel, one that evidences the delicate balance of beauty and pain. The “exquisite” character of this vessel invokes simultaneously an exquisite work of art and the exquisite ache of an intense sensation. By bringing to the fore a focus on form, in both the structure and the concept of the collection, we use the term exquisite vessel not just to name the work done herein but to draw attention to form as a creative and literary practice of reverence for the exquisite in its most literal sense of something carefully sought out. To essay is to try, test, and practice. The form of the essay, then, is a fitting site for the experiential and sometimes painful work of seeking answers. Many of the essays contained herein linger in these painful places, exploring the legacies of trauma and violence extending from personal to collective inheritance. Many are haunting, and few offer easy answers. Such is the possibility of form-conscious nonfiction, though. To write nonfiction is to render experiences, memories, observations, and interpretations through prose, a process necessitating writer agency and allowing for emotional depth and transformation—not only of the narrator figure but of the writer who essays.

My introduction nonfiction craft was really an introduction to form. I learned that I had been working with form in my previous work in short fiction, even though I didn’t totally know what form was, or that it was everywhere, in everything.

In writing essays that asked readers to consider form as a primary concern of the essay, an actual thing the essay is about, I was doing something non-Native readers didn’t expect, but also doing something Native writers and other artists had done forever. What I once thought of as formal innovation is not, exactly, because innovation suggests newness. While fragmentation, gaps, braiding, and emphasis on the visual presentation of the text layout have recently been considered innovative or experimental by the literary mainstream, these qualities have been Coast Salish methods for a long, long time. This is evident in the construction of baskets, each an exquisite vessel whose shape and construction are chosen with a mind toward the contents that will be carried.

I’ve seen baskets in non-Native art collections, divorced from their people, contexts, and purposes. Baskets are for clamming, berry picking, water-boiling, root gathering, and other sustaining practices; they are beautiful, they are exquisite, and the processes they make possible are foundational to Native life.

There’s been a good amount of discussion about artifice in creative nonfiction: the act of rendering and arranging, some argue, results in a sort of false object from the raw material of the truth. I agree that essaying is the work of making something new, but the essay isn’t a trick or a fake. It’s not an artificial proxy for past experience and not just an art object. Essays are life-sustaining, allowing us to come to new ways of knowing by giving textual form to our understanding as we come to it.

The notion of artifice was useful to me in developing my relationship with essay form, but I now focus on materiality, which recognizes a text as a built object, the fact of its construction at the core of its realness. Taking advantage of the essay’s shapeable features allows an essayist to bring form to style, character, and progression, resulting in a finely-crafted work whose depth extends beyond bare recollection or reflection.

In creating this collection, we wanted to honor Native writers’ work of transformation accomplished through craft and visible through the results of formal decisions in shaping essays. To return to Levine’s work on form, the generation of logic through essaying can actually facilitate transformation as the essayist creates and works within a system of reasoning, connecting, selecting, refusing, and ultimately, understanding through movement along a process of answering a question. The work makes its own pain of processing and ecstasy of understanding. Even if the “now” of the essay is invisible to the reader, the narrative present is the point from which the self in constant flux makes its meaning. As we are located in time, we are situated in place. Robbing the essay of its time and place is a colonizing gesture, because colonization severs bonds between people and place. It tells us that where we are and where we’re from don’t matter. It allows for floating, ungrounded meditations to be centered and canonized.

I was told that the 16th-century writer Michel de Montaigne gave us the essay. His legacy is undeniable—“I am myself the matter of my book”—and his influence certainly shows up in my work, even though I mostly came by it indirectly, but I want to challenge the notion that he is essayists’ common ancestor. Most of the writers whose work appears in Shapes of Native Nonfiction came to the essay after developing their craft in poetry or fiction. And, as Ernestine Hayes writes in her essay that opens the collection, in comparison to American narrative norms, “Indigenous artists tell different stories and advance different values. Indigenous artists are the storytellers of their generations. Indigenous artists are their generations’ witnesses. As much as any fairy tale, those stories remain alive and carry their testimony into the millennia.”

When I was on the academic job market in 2016, I was asked in interviews to speak about my influences and the history of the essay. I decided to be honest: I had no use for Montaigne; I wanted to talk about baskets, because doing so gave me a way to talk not only about formation, utility, and visual appearance, but also about lineage and the dynamic work of maintaining Indigenous knowledges. Basket weaving, while done individually, draws from community tradition and contributes to the continuance of Indigenous knowledges. The finished basket doesn’t only serve the maker: it might be used for generations. The food it might be used to gather will feed relatives.

When we talk about basket weaving, we’re conscious of traditions that are both old and current. This is work against stagnation, against fixity. We reject the ancient/contemporary dichotomy and instead embrace the abundant evidence of continuity. Essays are sites of contact between exterior and interior—between place and mind, between pressure and imagination. Where and when we make them matters; who taught us matters; what we carry matters.

The finished essay gives life to those who read it and recognize something they need to see. In As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson writes, “Reciprocal recognition, the act of making it a practice to see another’s light and to reflect that light back to them, forms the basis of positive identity, self-worth, and dignity in the other being.”

Settler readers who focus on trying to figure out whether or not we’re even “real” and use colonial metrics and markers of identity to do so are not seeing our light, they are not recognizing our dignity, and they are not honoring our self-worth. The images built from amalgamated settler expectations of “authenticity” and projected onto us—that’s artifice. By honoring these collected essays not for what they can do to illuminate “Native experience,” but for all that they are in process, object, and impact, we see these writers’ light. We don’t approach their work, and specifically their recounting of experiences, to consume; we know that we are lucky to be invited to witness the work of discovery and transformation. We see their work; we see their craft; we see their light.

I think often of my visit to Ed Carriere’s house in 2017, a few months before I left Coast Salish territory in service of my work. My friend Cynthia Updegrave, who had arranged the visit, took a photo of Ed talking to us and showing us a basket while wearing a cedar whaling hat. He was lit from behind, with the sun coming in through the big living room windows. I don’t know what happened to the photo, but I have it in my memory: he appears as an unlit shape, man, basket, and hat all one, unified by the light at his back. When I think of that image, I have a visceral memory of that warm room, filled with students and colleagues, some of us getting a little sleepy, lulled by the cadence of Ed’s voice and the calming pace of his narration. When we looked at the photo later, Cynthia and I agreed that Ed looked like a portal, the whole image a little bit otherworldly, but really, all that light and shadow is the center of that world in that place. We craft baskets and essays with that light behind us.

Theresa Warburton: I’ve worked on these comments in a number of places in the past few weeks: Lummi territory in Bellingham, WA; Narragansett and Wampanoag territories in Providence, RI and on Cape Cod; and Pennacook Territory in Lowell, MA. And then, of course, yesterday, I ended up here—a home of the Three Fires Confederacy of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi and an important meeting place for numerous tribal nations, including Kiikaapoi, Miami, Menominee, Sac and Fox, Ho-Chunk and others. Current home of Meštrović’s Croatian-born bronze sculptures The Bowman and The Spearman that lead one into Grant Park. A home that has long been and continues to be an important meeting place for Native peoples from all four directions. Home to a hockey team that still has that fucking mascot. It was also once my home, many years ago. And though I only lived here for about a year, it’s a place I’ve found myself often returning, undeniably because of the ways the practices of meeting, sharing, crossing, and relating have been part of the story of this place since time immemorial.

And, of course, home of the Field Museum, founded after the World’s Columbian Exposition. Organizers worked with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to create exhibits depicting Native peoples as passive populations who were positively changed by the institution of reservation life. This founding was only four years after the massacre at Wounded Knee, and the museum now holds over 40 million specimens and objects. At the Field Museum, dedicated curators, community members, local activists, and scholars help us learn to live more responsibly with, in, and through these legacies. I want to think through them in my field of Native literatures as well.

A few stories are told about the history of Native literatures. When I think about how to tell them, I recall a quick conversation with a camp host at Grand Teton National Park, another important meeting place that brought together Shoshone, Blackfeet, Crow, Interior Salish, Gros Ventre, Nez Perce, and other tribes from across wide swaths of Turtle Island.

When I arrived to camp for a quick night, the man made small talk with me. I had just graduated from my PhD program and was making my way from Haudenosaunee territory in Buffalo, NY to Lummi territory in Bellingham, WA, where I had just gotten my first job. Interspersed with the basic questions about equipment and length of stay were typical questions that come with working in a place that continues to be a meeting place for people from all over: where are you from, where are you going, what do you do. As we moved along this line of inquisition, I finally got to say: “I’m a professor of Native literatures”—the very first time I had gotten the chance to say that. “Oh yeah? What time period you look at?” he asked. “Mostly post-World War II,” I said, though anyone who teaches Native literature (or Native history or Native art or anything in Native Studies) basically knows that we are rarely afforded the opportunity to be this circumspect about our temporal boundaries. He cocked his head, narrowed his eyes, and said “Huh, I guess it would have to be that, right? Not really any literature to speak of before then.”

This is the most popular story about Native literatures. It circulates in Ivy League classrooms, within scholarly texts, around campfires in National Parks. It’s a story that assumes a neat, linear trajectory between orality, material culture, and writing. It assumes that that trajectory parallels that from savage to barbarian to civilized. And it assumes that literature is a term compatible only with the latter.

In the study of Native literatures, we see this story persist in two ways:

First, through the popular genealogy of Native literatures, especially nonfiction writing, that locates its origins in the 18th century before turning to fiction and poetry in the late 19th and early 20th, having only returned to nonfiction in the later period through as-told-to biographies or fiction that was assumed to border on personal memoir, because what else could a Native author possibly write besides their own life story?

The second way this story persists is in how the relationship between written literature and material objects is narrated. For many scholars, like archaeologist and anthropologist Patricia Rubertone, “archaeological evidence, as the material record of everyday life, [allows us] to compensate for the gap created by indigenous nonliteracy.” This approach understands material objects as stand-ins that can help piece together a regrettably more haphazard version of the kinds of stories and records that supposedly emerge from a more civilized written record.

These stories are suspect for a number of reasons. First, the presumption of orality as an uncivilized form seems strangely at odds with the claims to superiority of a European literary tradition that is rooted in texts like the Iliad and the Odyssey, both of which were passed down orally for generations before being written down. Or the work of Shakespeare, which most audiences would only experience as a performance rather than on a page.

The presumption of orality as an uncivilized form seems strangely at odds with the claims to superiority of a European literary tradition that is rooted in texts like the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Second, this assumes a hierarchical rather than relational correlation between material objects and the written word. As Abenaki scholar Lisa Brooks has argued in her study of early Native writing in the Northeast we must develop an understanding of Native writing not as a static body of work but as an ongoing practice that works to “spin the binary between the word and the image” or, in this case Rubertone’s “material record” “into a relational framework.” For instance, Brooks looks at texts that are often read as material objects, things like birchbark drawings or treaties formalized in wampum, to show that the history of Native writing is extensive and indelibly intertwined with material objects and the histories they are meant to carry.

We begin the collection with this passage:

The basket. The body. The canoe. The page. Each of these vessels has a form, a shape to which its purpose is intimately related. Each carries, each holds, and each transports. However, none of these vessels can be defined solely by their contents; neither can their purpose be understood as strictly utilitarian. Rather, the craft involved in creating such a vessel–the care and knowledge it takes to create the structure and shapes necessary to convey–is inseparable from the contents that the vessel holds. To pay attention only to the contents would be to ignore the very relationships that such vessels sustain. Yes, the basket may carry elderberries or trap salmon, but what of the cedar used to weave it? What of the weaver whose skills connect long genealogies of craft and kin? What of the cosmological significance of the elderberries and the salmon? Some weavers know how to weave baskets so tightly that water can be boiled in them. How can we think about that water, about the running of rivers and the running of salmon, without thinking of the craft that must go into a vessel that can hold water, whether basket or riverbed? To speak only about the contents of these vessels would be to ignore how their significance is shaped by the vessels that hold them.

This is how we work to reorient the relationship between material and literature, to rethink the assumed supremacy of one over the other. And this approach changes our understanding of the history of Native nonfiction as well. For me and Elissa, this was one of our core ethical commitments—to insist, in both word and deed, that Native nonfiction has actually been foundational to the field of Native literatures (rather than ancillary) and that if we center it within the conversation we end up expanding the history of Native literatures by thousands of years.

Material objects are not metaphors, in this sense. They do not figuratively carry story—they do so both literally and literarily, a point Elissa will return to in her comments in a moment. Material is the stuff of story and, for those stories to be held, they need to take material form. The basket is a material form. The page is a material form. The book is a material form. The essay is a material form. All circulate in different ways, all do the important work of building and maintaining what Brooks has called “networks of relation.”

In one of the epigraphs to the introduction, we draw on the collective work of I-Kirabati and African American writer Teresia Teaiwa and Lenape scholar Joanne Barker, who write:

Indigenous peoples understand that there is no difference between the telling and the material. They understand how we all, in fact, live inside and through the narratives we tell and that the importance in telling stories is inseparable from the identity, community, and history they compose and the spiritual, economic, and political realities on which they depend and which they subvert or preserve.

This relationship, between the material and the story, is, I think, one of the things that most brings together the work being done here at the Field Museum and the work we are doing in Shapes of Native Nonfiction. In each case, we are trying to better understand what is natural, what is historical, what is literary, and what is material about the sets of objects, relations, and stories that make up the fuller picture we hope to honor by reframing the histories and legacies we’ve inherited. For instance, where and why does the archiving, display, and relocation of Native material objects, from the mundane to the sacred and sometimes even including human remains, fit within the parameters of “natural history” often described as a specifically scientific study of organisms in their environments with an emphasis on observation rather than experimentation and on popular presentation rather than academic form? Why are so many of the kinds of storytelling objects, objects, that Elissa and I invoke in our introduction housed in natural history museums or private collections, often completely separated from the bounties of Native literatures that live in libraries and special collections?

This isn’t to say there is nothing useful about the terms, parameters, or practices of “natural history.” In fact, by invoking the basket, we are hoping to signal how much there is to gain when we see these histories, these practices, and these genealogies as cyclically connected rather than linearly separated. So, we must understand the history of Native nonfiction as inextricably bound to the history of material objects that are held in museums like these, like those we are in the presence of right now.

But, as these essays show, we must also understand the present and future of Native nonfiction as connected to material objects in this same way. I’ve worked here to point out the genealogical connection between the nonfiction essays by the contributors in the collection not to relegate them to a romanticized past, but rather to emphasize the fact that these essays are in a dynamic relationship with various times and spaces, calling upon objects, insisting on the materiality of the word, shaping an essay out of material that’s been persevered and making new material where it hasn’t been.

Much like the city of Chicago, these essays and these baskets evidence the importance of recognizing what Teaiwa and Barker call “Native in formation,” or an understanding of indigeneity that depends on a sense of movement, of being in constant relation. Rather than dislocating Native peoples from the land to which they belong, this term highlights the myriad systems of relations that Native peoples have developed and maintained since time immemorial—systems of relation that involve everyone, including those of us who are non-Native. These stories and these objects are static in neither time nor place; instead they provide an ethical root, a path forward and back, that can help us reckon with the indelible histories that live with the land as we live with it. And can teach us, in our most aspirational vision, how we might do so responsibly and with care.

__________________________________

Shapes of Native Nonfiction, edited by Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton, is available now from University of Washington Press.