On Seinfeld and the Mundane Fantasy World of the Three-Camera Sitcom

“I’d trade every vacation I’ve ever taken for a life of drop-ins with friends and family and a refrigerator that magically replenishes itself.”

My daughter was born in September of 2021. A month later, Seinfeld came to Netflix.

Before her birth, we’d scoured Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace looking for a used “smart” bassinet capable of increasing motion and white noise to lull baby back to sleep if they squirm or fuss too much. We found one in Iowa City, about a two hour drive each way.

My mom, meanwhile, gifted us a nice rocking recliner, which we could use to comfort both the baby and ourselves. We purchased noise machines and blackout curtains and all sorts of other stuff. Despite these investments, when it came time to sleep, my daughter wanted only one thing: to bounce on the $10 exercise ball we’d bought to use during labor.

And so, many hours were spent holding a swaddled newborn while bouncing up and down in a living room whose only dim light came from a television quietly playing the uneven early seasons of Seinfeld, a show I hadn’t watched in earnest since I was in high school.

Every television show is a closed universe in some way, but the three-camera sitcom shrinks the world even further.

I want to be clear here, this isn’t an essay about parenthood. I can’t write an essay about parenthood, because I only have two pieces of parenting wisdom to impart. The first is hinted at above: There exists no connection between something’s monetary value and its value to a baby. My daughter’s favorite toy is a simple teddy bear from someone my wife knows through work. Her second favorite toy is an empty, rinsed-out Gatorade bottle. And her favorite book is one we bought for a dollar at a book sale.

The other piece of wisdom: don’t write a parenting essay after only sixteen months as a parent, because every time you think you’ve cracked the code, a new issue arises that is almost definitely the result of some seemingly ingenious parenting hack you employed a month earlier.

This isn’t really an essay about Seinfeld either. It’s about a certain fantasy of what adulthood might look like, one inspired by the series (and also the three-camera sitcom broadly) that I’ve harbored for a long time and one whose origins I didn’t realize until recently.

Every television show is a closed universe in some way, but the three-camera sitcom shrinks the world even further. A city as big as New York can be reduced to a series of living rooms, diner tables, and occasionally, only when it is absolutely necessary for a laugh, workplaces. Nobody is ever stuck in traffic onscreen unless it’s crucial to the episode’s central bit. Otherwise, the ease with which the characters get from one place to another seems almost to imply a series of secret tunnels.

Though the novel is mildly dystopian, it’s also a fantasy of simplicity that is, to me at least, comfortable.

I’ve always wanted this, I realize now: a small corner of the world that I don’t have to leave, where I am occasionally visited by the people whose company I enjoy the most (or whose company I can dread in an entertaining way), and a job that casts only a vague shadow across a personal life of hijinks and witty repartee. I don’t need to travel. I don’t need adventure. I’d trade every vacation I’ve ever taken for a life of short drop-ins with friends and family and a refrigerator that magically replenishes itself.

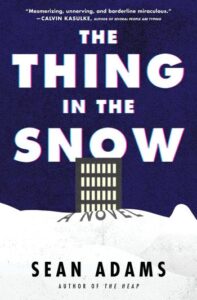

The Thing in the Snow, my second novel, was already finished—or at least the draft that I’d eventually sell was—when I started rewatching Seinfeld from the beginning, but its sitcom-inspired qualities are still apparent.

The story takes place entirely at a remote mostly-abandoned research facility called the Northern Institute surrounded by never melting snow. The entire sprawling building is now occupied by four people: Hart, our narrator, and the supervisor of a small caretaking team; his two charges, Gibbs and Cline; and Gilroy, a single remaining researcher. A few other characters make appearances—some in person, some on the pages of the novels Hart reads—but for the majority of the book, this accounts for the entire cast of characters.

The tasks Hart and his team complete can be characterized as tedious and sub-custodial. They rarely ever do something as active or engaging as cleaning. Instead, they open doors and listen to make sure the hinges don’t sound too loud or sit in chairs to test their structural integrity.

It’s not meant to be an appealing place. It’s cold, desolate, and boring, so boring that Hart’s team grows increasingly obsessed with an object they spot out in the snow, despite the fact that they can’t identify it or even make a list of its most basic characteristics. Most of the time, everyone is either miserable or else experiencing the sort of frantic glee that can only lead to lower lows later.

Despite all this, I felt a lot of joy while I was writing the novel. It made me glad to create such a compact world, a series of drab yet oddly cozy rooms and small obstacles with equal potential for both comedy and drama. And so, though the novel is mildly dystopian, it’s also a fantasy of simplicity that is, to me at least, comfortable.

I’ve done my best to live the three-camera sitcom life myself. I write copy part time, take care of my daughter, and cook meals for my family, which allows me to occupy a small corner of the world just like the dad in a show might. Occasionally, we eat dinner with friends or go to the botanical garden to avoid going stir crazy on bitter Midwestern winter days or do something else that could easily be preceded by “the one where they” on a list of the episodes of our life.

Yet, I still have to go to the grocery store when I discover we’re low on something we need for dinner, and my daughter’s afternoon nap—a time to read—might be hijacked by a call back from a handyman to discuss gutter repairs. Unlike the minor inconveniences that befall the likes of Jerry, Elaine, George, or Cosmo, these instances possess little potential for laughs and rarely set something larger in motion that becomes a delightful recurring joke in my life.

But hey, I guess that’s what fiction is for.

__________________________________

The Thing in the Snow by Sean Adams is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Sean Adams

Sean Adams is a graduate of Bennington College and the Iowa Writers' Workshop. His fiction has appeared in Electric Literature's Recommended Reading, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, the Normal School, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, the Arkansas International, and elsewhere. He lives in Des Moines, Iowa with his wife, Emma, and their various pets.