On Rediscovering the Natural World Through Ovid

Nina MacLaughlin is Seeing Green

I haven’t read the new books about trees. But sometimes I have to resist pressing myself against the sycamores that line a stretch of Memorial Drive that runs along the Charles River. They’re just so thick.

A natural thing, this attraction. A natural thing, to sense personality in the plants, the creatures. In the gingko tree, the autumn clematis, the red tailed hawk, the bank of cloud, the dandelion. It’s a variation of synesthesia, the sense-blending brain feature that allows one to taste the color yellow, to smell a b-flat from an oboe, to see the shape of a week, or to sense the specific disposition of a letter, a number, a dahlia, a stone.

The—is ability the right word? condition?—has gotten stronger over time for me, a more pronounced experience sensing the varied characters of the natural world. In part, it comes from a different aiming of attention: instead of stomping down the sidewalk stewing about this or that, instead of having imaginary arguments over years-ago wrongs, the world outside my skull draws me more now. There is so much to look at. The waxy shine of the holly leaf with its pricked edges pulls me toward it, the white splay of flowers on the honey locust, the late afternoon light glowing in the soft fronds of silver feather. Each presents itself and offers up a slew of associations.

Does it make me a hippy pagan to admit I’m in a relationship with these forces? Their textures, the depth of their colors, the way they reflect the light. A flowerbed of daffodils, a confident yellow horn section, noisy and cheerful as a parade. The birch trees, erudite, professorial. The cedars and their storm-color berries, observant and reserved. The deep blue cups of the morning glories on the vine on the fence on Sparks Street, inviting, cajoling, enter here. And, since it is November now, the milkweeds which have split and spill their white silk in one of the most thrilling and erotic displays earth offers. I cannot get enough.

Perhaps, too, it is a simple matter of time. A closeness comes from an every-day giving of attention. It’s automatic. Something cannot be a part of the rhythm of your days and not become an intimate. In time, we reveal ourselves to one another. We grow close and closer, as with a friend, a love, the members of one’s family, so, too, a city block on the commute, the shifting light, the shape of the leaves on the Japanese maple around the corner. The tiny patch of lavender on a corner near my apartment that I see each early morning, a version of a friend. I am curious about it, interested in its presence and its growth: Who planted it, I wonder. Why’s it here?

I also wonder if my readings of Ovid over the last few years have increased my awareness of the natural world. In his Metamorphoses, human figures get changed to stones, trees, springs, bears, bats, horses, echoes, swallows, stars. Sometimes, the transformations come in the form of protection—be a bay-leafed laurel tree instead of raped by Apollo. And sometimes in the form of punishment—be a spider and forevermore weave webs for your hubris. A moment from the sad story of Dryope stays with me.

I also wonder if my readings of Ovid over the last few years have increased my awareness of the natural world.She’s raped by Apollo but it does not undo her. She gets married, has a baby, and one day by a pond she’s showing the flora and fauna to the infant in her arms. Oh look, sweet pea, a lotus tree in bloom, look, these deep red-purple flowers, she says, and she plucks one for her babe. Bad news: blood drips from the stem. Dryope’s made an error. She didn’t know—how could she?—that the tree was once a nymph named Lotis who was chased by Priapus, he of the arm-sized dick, and to avoid his violation, she was transformed into the lotus tree. Dryope, in punishment for plucking the flower that was the nymph, is changed into a poplar tree and her tiny baby tries to suck milk from her bark. There is none. Before the bark overtakes her face and silences her forever, she claims her innocence: “If even sorry wretches have the right / to be believed, I swear upon the gods / that I did not deserve this horrid end.” And she begs her husband to keep their baby “far from pools; and he must not / pluck any flowers from trunks; and any bush / he sees—he must remember this—may be / the body of a goddess.”

Any bush, the body of a goddess.

The way I’ve internalized it—and it does feel like something that has been absorbed into my body—is not the warning, not the cautionary don’t touch, don’t pluck, be afraid, danger lurks, but more the idea of unknowing. Who knows who this might’ve been, which is to say, who this is, still now? What inhabits the batons of cattails on the riverbank, the glacial erratic just off the path, the milkcow in the pasture, the crimson-berried bittersweet? What grim fate were you saved from? What crime were you punished for? It doesn’t keep me from clamoring on the rock; I love to kick an acorn; and milkweed, husks and innards, feature in much of my home décor. But it does deepen my relationship, curiosity, and respect.

Because who knows what happens next? A geneticist who helped map the human genome at MIT told me that there are infinite options for what happens after we’re dead. He didn’t say that’s it, when you’re done you’re done, finito, nothingness. The scientist said, “Anyone tries to tell you what happens afterwards? Walk away.” The only fact is, all of us die. After that, no one knows, and it’s up for grabs. Ovid’s explanations, as good as any. Who’s in that cactus, that aspen? Under an oak on a patch of Cambridge grass, acorns everywhere like wooden marbles, a dominant splaying of seed. I kicked a few, watched them bounce and roll. All this potential energy under those small brown caps, each acorn a tiny fist of possible tree. Spread on the grass, the whole population of them, they’re playful, mischievous, aware, somewhere, I think, of coming into their power. Who were you? Who will you be? How will time change you? Anyway, it gives me something to think about as I run along the river.

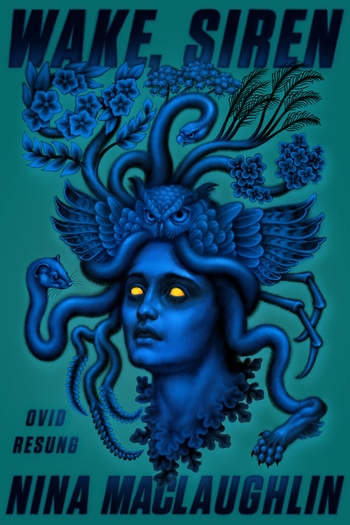

And it gives me something to think about now. I am writing this because I did not want to write an essay about rape. I did not want to focus my attention on violence and violation and being silenced. I wanted, instead, to think about the plants. And though I was not conscious of it at the time, when I was working on Wake, Siren, which is a violent book, I lavished attention on features of the natural world as antidote, tried hard to make vivid the natural world with words. I did not know it then, but doing so served as balm, a reprieve from the depravity and brutality that thundered daylong in my mind.

How do we make ourselves at home with change, is the question Ovid asks of us. Time is violent, silent, and though it holds different events for all of us, no matter what, it will change us all. How do we continue to emerge, altering, altered? How do we continue to locate a sense of at-homeness in our selves and our worlds? The geese don’t have to ask it, nor the elm trees, nor the moon. We have the burden and the luxury.

Last night fell below freezing, first ice on the puddles. This morning on an early walk, I rounded a corner to find that the gingko tree, which yesterday was fully dressed in gold, had dropped its leaves in one complete cold-night shedding. It happens fast. The ground around it, a golden puddle. I crouched amidst the glow, grabbed an armful of the leaves. I held them against me in my hands—their life was undeniable—and brought them home. To what end, I don’t know. They lie now on the floor by my chair, and I can see the life leaving them, but they are alive right now. As we are. Everything around, so spirited.

_______________________________________

Nina MacLaughlin’s Wake, Siren is available now in paperback.