On Reconnecting With My Korean Heritage Through Food

For Peter Serpico Cooking Feels Like Coming Home

Korean food nourishes me in a way nothing else can—the kind of fulfillment you experience so deeply that using words to describe it seems like a disservice. The easiest and most accurate way to put it is that it just feels right.

When I eat Korean food, I feel better. The give-and-take of salty and sweet. The appealing balance struck among fermented funk, fishiness, and invigorating spice. The wholesome, vegetable-centric approach—“clean” eating, centuries before it was cool. The universe of flavors unlocked atop the building blocks of kimchi and white rice, cornerstones of every meal that partner so well, despite having nothing in common.

I know this is what you’d expect to hear from a Korean person, especially one who works as a chef. But I wasn’t always so in tune with my culture, my cuisine, or myself. The truth is, for much of my life, I had no connection to anything Korean whatsoever—originally by circumstance, and eventually by choice.

I’ve heard many chefs speak of the moments that made them fall in love with food: fond recollections from childhood, cooking side-by-side with parents or grandparents and sharing cherished family recipes. As their careers progress, they expand upon these deeply personal flavors, relying on high-end skills to maximize their impact on diners—maybe creating new memories in the process. Turns out I’ve taken the exact opposite route. I came up in this industry not knowing a thing about the cuisine running through my veins. Instead, I decided to dive in after experiencing success on a professional level.

For much of my life, I had no connection to anything Korean whatsoever—originally by circumstance, and eventually by choice.

Many different factors motivated me, but family is by far the biggest. Cooking is my life’s work, yes, but my wife, our daughter, and our loved ones, Korean and otherwise, have all helped me see food for what it should be: not a vehicle for ego, but a selfless expression of generosity and care. It took me years to sort this all out.

*

My name was Kyung-ho. I was born in 1982, and I ended up at an orphanage in Seoul—not quite as dramatic as being left on a doorstep in the driving rain, but something along those lines.

I first met my parents, Dennis and Sally Serpico, when I was about 2—a doctor’s best guess based on the length of my bones, since my birthday wasn’t written down anywhere. After several years struggling to conceive, they’d adopted my older twin siblings, Danny and Terra, from Bogotá, Colombia, coming into contact with the orphanage through an organization in Maryland. By the time they wanted to adopt again, the laws in Colombia had changed, so they began looking elsewhere. In 1980s America, it was often easier to adopt from overseas, and South Korea, for many reasons, had one of the most navigable systems of the era.

That is the short version of how Kyung-ho, the Korean orphan, became Peter, the American chef. I don’t like to see myself as the beneficiary of arbitrary timing, and I don’t want to think of the life I’ve built as a byproduct of chance. But knowing where I started, and how easily I could have ended up anywhere else but here, has a way of putting things in perspective.

Knowing where I started, and how easily I could have ended up anywhere else but here, has a way of putting things in perspective.

My dad still tells the story about the day they brought me home. Peter was as neat as a pin. Right off the plane, he went into his room, took out all his clothes, folded them, and put them away in a drawer. I was already potty-trained, and I had a great appetite. My good habits, apparently, made the 7,000-mile trip with me. My favorite meal was fish and rice, which my mom took pains to prepare for me on top of the food she was cooking for everyone else. To her relief, I adapted quickly. Before long, I was enjoying spaghetti, green peas, and garden salads with ranch dressing, same as everyone else around the table.

On paper, I wasn’t different. I took the same classes, played the same sports, ate the same food, watched the same movies, listened to the same music, and worked the same jobs as boys my age. But when you’re the lone Asian son of white parents whose other children are Latin and Caucasian (Jackie is my parents’ biological daughter), the reality is you stick out, no matter how “normal” you feel.

Howard County is a reasonably diverse place, and I’m privileged to say I didn’t experience much discrimination growing up there, beyond a few isolated incidents. My baseball coach referring to me as “Ching Chong” in front of the entire team at practice one day comes to mind. I called him something back, and suffice it to say I never heard that one again. Things were different, though, when we’d visit my grandparents in Chicago. Being young, I didn’t pick up on this as sharply as I might now, but my dad says he would always put his guard up when we were out in public together. He knew the judgmental stares from strangers were coming.

I was well into my adult life before I began to grasp how my adoption shaped my views as a person, husband, father, and chef. Growing up, though, the topic didn’t come up all that often, and I learned to like it that way.

Over the years, I’ve discovered that there are certain childhood dynamics common among transracial adoptees. One is the notion that if your immediate family doesn’t “see” your race, then it should be a nonissue for everyone else, too. It comes from a place of protection, but it can also breed confusion—as well as you might fit in at home, that contentment doesn’t automatically come with you when you walk out the door. The author Nicole Chung, a fellow Korean adoptee, talks about this in her memoir All You Can Ever Know. “Caught between my family’s ‘colorblind’ ideal and the obvious notice of others,” she writes, “perhaps it isn’t surprising which made me feel safer—which I preferred, and tried to adopt as my own.”

While many adoptive parents are hesitant about the topic, afraid of fostering resentment or alienation in their kids, my mom and dad never once tried to downplay that Danny, Terra, and I were not their birth children. On the contrary, they wanted us to embrace our heritage, and got us involved with cultural groups designed to do just that. They also offered to help us find our birth parents, if that’s what we wanted.

Looking back on it, I think I was hesitant because I never wanted it to seem like I was disrespecting my parents by formally acknowledging I was not biologically “theirs.” They were always incredibly loving and supportive, and who knows where I’d be without them. Nicole Chung puts it much better in her book: “It would have felt like the greatest of betrayals to tell them I didn’t belong in this place, this town, this life—all they would hear, I felt sure, was that I didn’t think I belonged in our family.”

Another common experience among transracial overseas adoptees—this one I could closely relate to—is the anxiety we feel when engaging with our birth culture. When I would interact with Korean people, via those social adoptee gatherings or just in day-to-day life, it always left me feeling like an outsider twice over. Yes, I looked like them. But I didn’t speak the language, understand the traditions, or eat the food, so my exposure to this culture—“my” culture, in the most clinical manner—had the opposite of the intended effect.

All this is to say that I’ve often felt stuck in a holding pattern between two worlds: a birthland I didn’t know and a homeland that didn’t always seem to know me. Technically, I’m Korean-American. But for the longest time, neither half of that term felt like it fit me.

People have asked me if my desire to dig up my roots grew out of working with Dave Chang, since he’s also Korean-American and there have been some Korean-inspired dishes across the Momofuku menus. The answer is no. The spark came to me in Queens, around a modest table covered end-to-end with the first, and best, real Korean food I’d ever tasted.

I met Julie when she was hired as a hostess at Noodle Bar, and someone asked me to train her on the POS system. We got along right away, and she kindly made an exception to her usual policy of not dating people from work. I learned she was a native New Yorker, and that she used to be a buyer in the fashion industry, which explained all the extremely on-trend looks that I, a devoted T-shirt and jeans guy, could not comprehend. I learned that, like me, she was figuring out what she wanted to do with her life, and that led her to restaurants. I also discovered that, while she was Korean-American, our upbringings could not have been more different.

I’ve often felt stuck in a holding pattern between two worlds: a birthland I didn’t know and a homeland that didn’t always seem to know me

KoriJulie’s parents came to America from Korea’s southern coast. While she lived as a typical young American woman in Lower Manhattan, back in Queens, she was a traditional Korean daughter. Her dad worked as a carpenter. Her mom, who ran a nail salon with Julie’s aunt, still found time to prepare food for the family morning, noon, and night. Instead of mac and cheese, Julie looked forward to sitting down to her favorite soup, whole blue crabs simmered in a spicy anchovy broth, with thick coins of daikon and freshly chopped chrysanthemum. My food memories tended toward sandwiches and supreme pizzas; Julie’s were more panfrying eel and peeling quail eggs.

There is a slight language barrier between Julie’s parents and me, but I discovered early on that no extensive dialogue was required for this new chapter of my education to stick. I learned by watching, and of course tasting. I saw how her mom would leave a pot of split pig’s feet simmering on the stovetop for days, creating a cloudy bone broth that was both versatile and elegant (page 79). I witnessed the amount of care that’d go into the marinade for short ribs (page 165), something that’s easy to take for granted when you’re shoveling down mountains of K-BBQ.

And of course there were the fermentables. Every spring, Julie’s mom and aunt would forage ramps from a patch in between their houses and turn it into kimchi that’d stick around through the summer. It was stored, along with dozens of other homemade kimchi, in a separate refrigerator designated solely for this task—a staple of all Korean households, yet one I had no clue about.

Julie and I eventually got married and moved to Philadelphia, and Charlie was born in the spring of 2015. Shortly after, my mother-in-law arranged to come down from Queens and stay with us for a few weeks. While mom and baby were the intended recipients of Halmoni’s helping hands, the visit was a gift of a different sort for me. I still remember her pulling up, her car exploding with Korean groceries—it was like she walked into H Mart and told them, “I’ll take two of everything.” Julie told me this was her own way of saying “I love you,” and after she started cooking, I knew exactly what she meant.

___________________________________

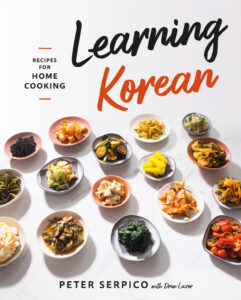

Excerpted from Learning Korean: Recipes for Home Cooking by Peter Serpico. Copyright © 2022. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.

Featured photos from Learning Korean: Recipes for Home Cooking by Peter Serpico

Peter Serpico

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Peter Serpico was adopted when he was two years old, and was raised in Laurel, Maryland. Serpico graduated from the Baltimore International College Culinary School and his first cook job was at the Belmont Conference Center, where he worked under chef Rob Dunn. In 2006, Peter began as sous chef at the original Momofuku Noodle Bar in the East Village. For the next six years, Serpico worked with David Chang to open Momofuku Ssäm Bar and Momofuku Ko. As director of culinary operations, Serpico earned three stars from the New York Times, a James Beard Award, and two Michelin Stars, among other accolades. Serpico’s highly praised eponymous restaurant on South Street in Philadelphia opened in 2013. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Serpico was reimagined as Pete’s Place. In 2022, Serpico and restaurant-partner Stephen Starr launched a revamp of Pod, a long-standing Philadelphia pan-Asian restaurant, as KPod, with a menu inspired by Serpico’s native South Korea. Serpico lives with his family in Philadelphia.