On Putting the Most Vulnerable Parts of Yourself on the Page

Justine Cowan Considers the Anxieties of Publishing a Memoir

I wish I knew of a support group for memoirists. While I’m grateful for a devoted husband and steadfast friends who always seem to know what to say, as my publication day approaches, I long for words beyond their reach, insights that only someone who had publicly exposed the most intimate moments of their life might offer. If they survived it, so could I, I thought. In an impulsive moment, I sent an email to the most famous memoirist I could think of, hoping she could calm my anxiety. I never heard back.

Doubts seeped into my every thought, my habit of mindlessly scrolling through comment sections on social media provoking a new reaction. What will they say about me? My uneasiness ripened into fear as I grasped the certainty that secrets I’d previously shared only with my spouse, closest friends and therapist soon would be laid bare. Now, my mind is cluttered with lists of those who might read my story—neighbors, acquaintances, and strangers, those I may have slighted, old boyfriends, employees I had to let go. I envision running into them, their smirks barely concealed beneath cloth masks. I feel a tightness in my chest as I wonder which passages caught their attention. They know more about me than they should, and their piercing eyes reveal that their judgment has been cast. I am beginning to panic.

What have I done?

*

My family dynamic was not for public consumption, I was always told. My mother spent much of her lifetime projecting a counterfeit version of herself. No one doubted that she was from an upper crust British family. Her air of sophistication was captivating, her chin raised ever so slightly as she spoke in a crisp English accent she hadn’t lost despite her decades in the States. Our home was littered with her well-constructed illusions: tastefully framed photos of my sister and me in fine white linen frocks with blue satin sashes, or in green-and-red-plaid taffeta at Christmas, portraits of smiling daughters that told the same misleading story. Things were not so airbrushed behind closed doors.

But secrets always come out, especially the big ones, and my mother’s was a doozy. She was not a descendent of nobility, but an orphan—or, rather, a foundling, raised at an infamous institution straight out of a Dickensian novel. The Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children, or the Foundling Hospital as it was commonly called, was established to rescue “bastard” children from the streets and turn them into useful members of society to clean chamber pots for society’s elite. The children were dressed in identical uniforms made of coarse brown serge to reflect their lowly station in society, and marched from place to place in a manner reminiscent of The Handmaid’s Tale. Their training to become England’s future servants was strict, and often brutal.

I was never close to my mother, and I am not sure I ever loved her. But it was difficult to write about her life, as I discovered it after her death. My mother had been given up because of the shame of her illegitimate birth, deprived of any tenderness, touched only for the purpose of punishment (and most likely with a leather strap or cane). My breath would catch in my throat as I dredged up stories of how she spent her childhood beaten and belittled by a sadistic headmistress, locked in dark closets, and left alone to experience unimaginable terror as the skies above Britain erupted into battle against the Germans in World War II.

As my publication day approaches, I long for words beyond their reach, insights that only someone who had publicly exposed the most intimate moments of their life might offer

But while it was difficult to talk about my mother’s life, it was nearly unbearable to describe the impact her tragic beginnings had on mine. At first, I didn’t even include my life stories in the book. But my editor knew that I needed to “go there” and would gently push me to open up just a little more. Soon I was detailing long-forgotten childhood memories so painful I could not even muster tears. No one prepared me for what it would be like to see these moments printed in a book. I avoided journals, and my memories have always had an ethereal quality, overexposed and granular, with soft edges and muted voices. I preferred it that way. Now they are razor-sharp, whetted with commas and prepositions. I’m shaken as I observe the arc of my life laid out in black and white.

I don’t know how it will feel when this all comes out.

Instead of a support group, I found comfort in the most unexpected of places—an email from across the Atlantic, from Lydia, my mother’s classmate at the Foundling Hospital. Like my mother, she too had been given up because of a “shameful” birth, a secret they were taught to hide for a lifetime. But Lydia was having none of that. “I used to be ashamed of my past,” she shared. “Now I shout it from the rooftops!” Indeed, she had become a celebrity of sorts, speaking to school groups and civic organizations, sharing stories of her time at the Foundling Hospital with anyone who would listen. She has appeared on television and met several members of the royal family, including the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Charles, and the Duchess of Cambridge.

I am enamored of Lydia’s free-spirited and joyful nature, so different from the aristocratic airs and closely guarded secrets that were my mother’s defining characteristics. On the surface, Lydia and I have little in common, generations apart, raised in different countries, but she instinctively knew that with the book’s release would come a certain amount of pain. “I am sure you have experienced a lot of sadness,” she wrote before going on to tell me that she was “so proud” of me. As I read her words, I felt foolish, my fears of divulging private thoughts insignificant in comparison to what Lydia has already disclosed to countless others—not to mention simply experiencing the unimaginable tragedy of her own childhood. The way she saw it, releasing the pain was the only way to find peace. My mother’s secrets were painful for her, and devastating for our family. As they festered in the dark, they ate us from within. Lydia’s past was hurtful for as long as she kept it hidden—she destroyed its power by having it reach the light of day.

I am determined to embrace Lydia’s approach to life. I am still terrified, but I find new strength in her example.

If she can do it, so can I.

__________________________________

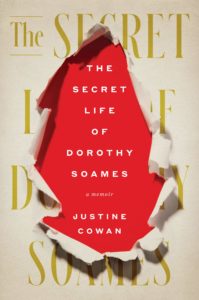

The Secret Life of Dorothy Soames: A Memoir by Justine Cowan is available now via Harper.

Justine Cowan

Justine Cowan is an attorney and environmentalist who spent over two decades exposing corporate corruption and holding polluters accountable. A graduate of UC Berkeley and Duke University School of Law, she lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. The Secret Life of Dorothy Soames is her first book.