On Planting Seeds, Excavating Language, and the Politics

of Place

Kerri ní Dochartaigh and Katie Holten in Conversation

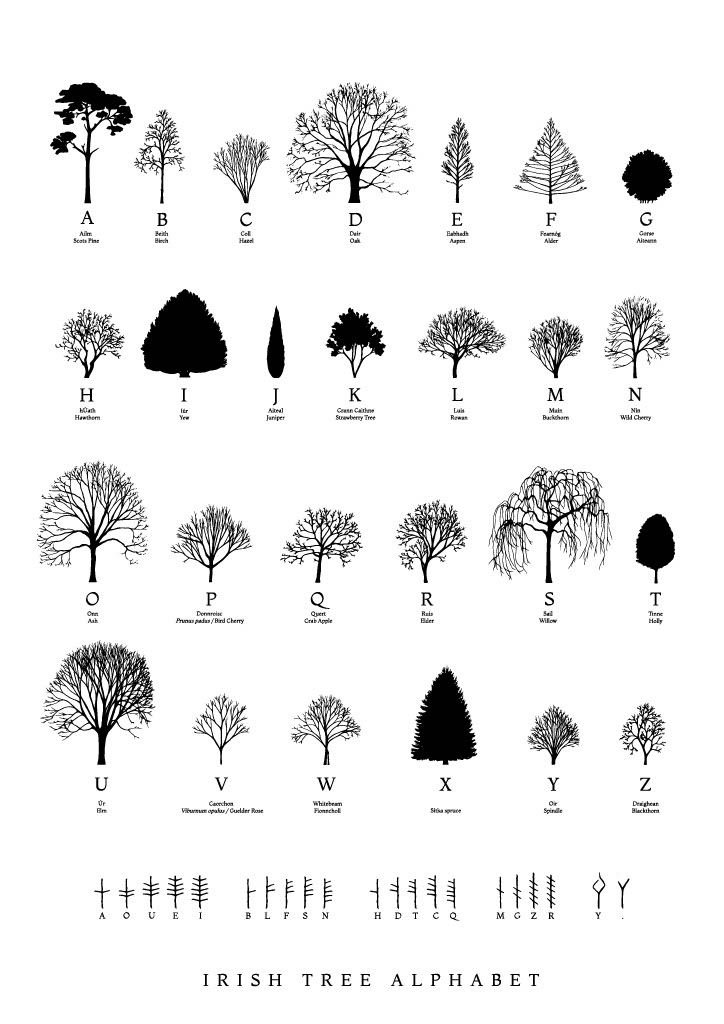

Kerri ní Dochartaigh is from the North West of Ireland but now lives in the middle, in an old stone railway cottage; the closest dwelling to Garriskil Bog. She writes about nature, literature and place. Her first book, Thin Places, is forthcoming in January 2021. Katie Holten is an Irish visual artist and environmental activist based in New York City and quarantined in Montecito, California. In 2015 she created a Tree Alphabet and made the book About Trees. She has just designed a new Irish Tree Alphabet, a writing system that translates text into trees. The work is currently exhibited at VISUAL Carlow, Ireland’s largest contemporary art space, through October 18.

*

Kerri ní Dochartaigh: I was incredibly moved by your exhibition, Irish Tree Alphabet. It felt essential and timely, fresh and ancient all in one. It will always be, in my memory, the visual reminder that, like strong oaks from little acorns, we still can create the world in which we wish to live. One where we care about the creatures we share this earth with, and where we acknowledge more fully our interconnectedness. I wonder if you could speak a little to what interconnectedness means to you?

Katie Holten: We’re all here together, growing and dying together on this planet. Trees breathe out, we breathe in. Some say language is what makes us human, but doesn’t everything communicate? I’m trying to untangle this. If we humans can’t twig what the other is saying, never mind all the other species, how can we live peacefully together? I started making alphabets as a way to slow language down, to slow myself down. It’s been strange drawing a new ABC of Irish Trees while quarantined here in California, surrounded by succulents and hummingbirds. The project invites thinking about natives, non-natives, species moving as climates change. Inevitably, I’ve incorporated Ogham, Ireland’s medieval “tree alphabet.” I’m struck by how organic it was. It literally grew from the ground up, like a tree sprouting letters.

Irish Tree Alphabet by Katie Holten

Irish Tree Alphabet by Katie Holten

KnD: The delicate act of paying attention is a beautiful act of love, as well I know you know. Long have I admired your passion for protecting this earth and what we share her with.

KH: We (humans) exist on one planetary scale, but there are so many others. We (species) share the same eternal story. We’re intertwined but we can’t get our languages to mesh. Our species—and so many others—on the brink of extinction because we’ve lost our grip, forgotten how to read and write our shared story. That collective human story, civilization, feels to me to be teetering on the edge of possibility. In the last six months, as we slipped into COVID-time, I’ve had an overwhelming sense that more people are awakening to this. Together apart we’re re-writing our story, excavating our future language fossils. There’s a palpable sense that we’re in the middle of our story. But no one knows how it’s going to end. Do you feel this too?

KnD: I love that you have spoken of time, it is a creature that long has drawn me in, close to where its porcelain bones and wings meet. During lockdown I read lots about Ogham, a language I’ve long been affected by. What depth of meaning our ancient languages hold… And trees, of all we share the earth with, hold time in close to their core; teach us how we might weather the storm over timescales both vast and shifting. I wonder if perhaps now we are in fact in a nameless time. One that it is our task to find words for. We know that it is up to us to make the changes needed to make this a safer, fairer world for us all, human and non-human. For me, time has felt like an insect, in these surreal, oddly boned days. I think I’m in “insect time.”

Photo by Katie Holten

Photo by Katie Holten

KH: I think of time as circular. Tree Time, growing out from the heartwood, in ever widening rings. What has it been like to put down roots? Was your book finished before the coronavirus arrived?

KnD: I edited my first book throughout early lockdown which was quite something given its content. Thin Places is a telling of my life growing up alongside violence, fear, and trauma—and how I made my way through by seeking places full of something almost unnameable. Places that felt almost too incredible to be real—neither here nor there—where the veil between worlds, people and ideas is lifted. In Celtic tradition these would have been sites where the self met the spiritual, and all that is there waiting for us if we draw in close. For me, these places—the wild ocean, rivers, coastlines, fields with ancient stones, gaps between grey housing estates—kept me here; reminded me that no matter how hard things got, I was a thing worth saving. To be held in place, unable to go into the safe nooks of the world around me during that process, really took me to a place I have only begun to understand; deep inside. Then after editing, I filled my days almost fully with sowing seeds, planting my first ever garden. This year has, without a shadow of a doubt, changed the landscape of my insides.

“I wish I knew, long before now, that sowing is a way to grieve. That planting and nurturing are personal and political acts.”I wish I knew, long before now, that sowing is a way to grieve. That planting and nurturing are personal and political acts. I’ve just finished re-reading Trace by Lauret Savoy, and have come away with an even deeper desire to learn more about the injustices faced by folk forced off the land they had cared for. It seems so essential for our understanding of how best we might begin trying to redress the imbalances; by really fully understanding the pain that has been inflicted for far too long.

KH: Trace is such a beautiful, important book. I re-read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. What else have you been reading? What’s helping you?

KnD: I too re-read Robin’s exquisite book and returned to Audre Lorde, from whom I seek great comfort, and discovered the work of Richelle Kota, which has utterly broken me; it’s so essential, raw and beautiful. I read handiwork by Sara Baume, and A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa, both with the incredible Tramp Press, and found such comfort in their stories; two resilient, creative women who are carving meaningful lives amidst the chaos. I re-read Elizabeth J Burnett’s The Grassling, too, so I suppose I have been drawn to strong female voices through this, and they have helped greatly.

KH: Some of your tweets feel like visual poems. Last week you shared photos of a moth and a cracked plate with the waning moon. Do you watch any films?

KnD: I don’t watch anything really, mostly I read and listen to the radio. If I have free time I go to the sea, it is my most beloved being, my teacher, my reminder. Do you swim?

“Over lockdown I found that, in a surreal manner, I was not wishing myself away to any place other than where I was.”KH: I’m afraid of water so I walk along the edge. I miss our fractal coastline. You mentioned that you were on the beach in Connemara reading Borges. You’re living my daydream! I’ve been revisiting long ago walks over there.

KnD: I was at Na Forbacha, looking across to the Aran Islands when we were messaging. I’d just swam beneath ringed plover, in the belly of the Atlantic Ocean, and felt so overwhelmingly alive and grateful for this life. Which parts of Ireland do you know best? Where did your roots begin?

KH: I grew up in Longford, only a few miles from where you are now. We weren’t farmers, but we were surrounded by fields, that’s where I played. My favorite place was in the trees at the edge. One of my earliest memories is going into that dark hedge space to a big tree, lying on moss, looking up. I’ve replayed the memory so often it’s like a comfort pebble in my pocket. When I was ten we moved to Ardee. That’s home now, that’s where my mother lives, on the edge of Ardee Bog. It’s an in-between place, quiet and soggy, surrounded by silver birches. I’ve been trying to protect it because like everywhere else, it’s under threat.

KnD: What made you move from this wee rock? What does belonging mean to you, in a world of leaders so keen to keep us apart?

KH: Isn’t migration at the heart of who we are? When I was little my father shared his world atlas with me. I adventured through the pages, thinking this beautiful planet is a shared story that we can read and write with our bodies in the landscape, innocently imagining the different colors represented nothing more than different languages. The innocence! Now Ireland’s a place migrants and refugees can call home (#EndDirectProvision). It makes me inordinately happy to see new members of Carlow’s migrant community visit the Irish Tree Alphabet, dancing with the trees, telling their own stories with their bodies. Where’s the place that you return to?

“I believe we are more similar and more connected than we have been told. And that with compassion, listening, the paying of full attention, we will write a new world.”KnD: Over lockdown I found that, in a surreal manner, I was not wishing myself away to any place other than where I was. It had never happened me before, that sense of rootedness, and I felt fiercely grateful. I started researching the land around me through its placenames. I did not learn Irish because of the political factors at play in my upbringing but when the eco-crisis really fully hit me, so too did the loss of my native tongue, and I immediately began trying to learn. I write about this in Thin Places, that the loss of our people, the land, native species, our language; it is all tied up with thick rope—and to untangle that means, to delve deep, holds the room for real healing.

KH: Yes, healing. It really did feel to me like there was a sense of possibility during the early stages of the pandemic. Maybe we would finally, collectively, feel the urgency of the climate emergency and act on it. The invisible threads of our systems were made visible. We need massive, systemic change if we’re ever to recover. But now, sadly, I hear people talk of going back to “normal” as if that were a good thing.

What about you? Do you see any hope in how our story could unfold? I know hope is a difficult word, maybe what we need is courage. I guess I’m wondering, what kind of future do you see? Do you think we can write it into being?

KnD: I’m convinced that the only way through this is together. No shaming, no separation, no us and them any more… We have long been encouraged to view things as removed from one another: those who love nature and those who don’t, those who are “from” a place and those who aren’t, those who have and those who don’t, nature and “us”—it simply is not the way things are. I believe we are more similar and more connected than we have been told. And that with compassion, listening, the paying of full attention, we will write a new world. I believe it starts with communication, with the full giving from one to the other—human to human, human to non-human and the other way round. We cannot care for or protect what we have never really listened to. It will not be easy, much pain is being carried by many and there is much needed to move into a place of equality for all. The Irish word for hope is dóchas, and holds, deep within its ancient roots, glimmers of the Irish word for giving, for belonging, for beauty: dóighiúil. Yes, we are ready, now, to speak of hope. I think we are finding the words for it, translating them into a universal language, and that changes things. In fact, that changes everything.