Katie Holten on Turning Words and Paragraphs into Whole Forests

Speaking With the Author of About Trees & Creator of an Arboreal Alphabet

Katie Holten’s tree project is the best example I’ve encountered in recent memory of a simple idea that carries the weight of something much more complex. Holten, an Irish-born visual artist based in New York City, has created an alphabet of trees that she uses to translate text into trees. About Trees, the resultant anthology, is a provocative examination on the nature of language and our relationship with the natural world as we enter a new age, what many geologists are calling the Anthropocene. As the breakdown of the natural world coincides more and more with that of the human world, and our interdependence becomes more apparent, such explorations grow more urgent. This urgency is one of the guiding impulses behind the new Parapoetics series published by Broken Dimanche Press, of which About Trees is the first title.

I interviewed Katie in September 2015, just as About Trees was published in a limited run. This edition of the book proved immensely popular and sold out immediately, which resulted in us putting this conversation on hold. A second printing, currently available through Broken Dimanche Press, will be available in US bookstores in September.

–Stephen Sparks

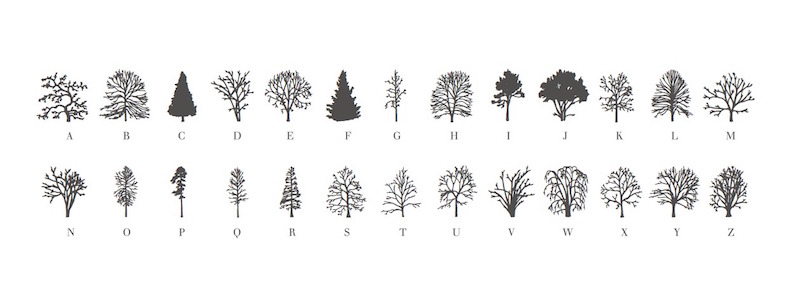

Stephen Sparks: Why did you decide to create this alphabet of trees?

Katie Holten: It needed to be done! It’s so simple, so obvious, like a children’s ABC book. My sister had identical twins and I’ve been reading baby books for the first time, so maybe that has something to do with it. The Tree Alphabet introduces a new ABC for adults. Some people like the fact that it’s educational—you can “read” the alphabet with your kids and learn to identify some trees—but that’s not really the point. At least it’s not the reason I needed to make it.

SS: Why trees and not some other natural element?

KH: I work in lots of different mediums, but I sort of got pigeonholed for a series of tree drawings that I made when I moved to New York. The drawings got picked up by people on sites like Pinterest and have this weird online life—they exist out there in the ether. People regularly contact me about getting one of my tree drawings as a print or a tattoo. I’ve always liked the idea of giving things away (I used to make a lot of booklets to accompany projects and they were free to take away). So, I’ve often thought: wouldn’t it be nice to make the tree drawings into something that people can access and use themselves?

SS: Do you draw any conclusions from the immense popularity of these drawings?

KH: The tree is a fundamental form. It’s a shape, a metaphor, a concept that we inherently respond to and find attractive. Trees have the potential to be read both abstractly and formally. There’s been so much written about trees and they’re embedded in so many different cultures… We’re made up of trees—branching structures form the tiniest parts of us—from neurons in the brain, the arterial system and our nerves, to our lungs and the split ends in my hair. Everything splits and branches like a tree. Even the computer programs we write. It’s life…

The tree is a fundamental form. It’s a shape, a metaphor, a concept that we inherently respond to and find attractive. Trees have the potential to be read both abstractly and formally.

SS: I was struck by the lack of context in the book. This must have been a deliberate choice.

KH: I never introduce my books, or my work in general. I’ve always felt that it’s not my place to tell people what to think about what I’m doing. Readers are smart. They don’t need to be told what to do, or think, all the time. What I do, is look at things and ask questions. I ask a lot of (often stupid) questions. It’s all about searching for Beauty and Truth, right? So I make simple studies into everyday things. For example, why is the “art world” not divesting from fossil fuels? I feel, strongly, that a lot of things are very fucked up. In Ireland we use the gentler word “fecked.” We’ve fecked things up big time and we need to change things—drastically and immediately. But I don’t want to lecture people and tell them what to think, or what to do. I like to investigate things and present what I find, preferring people stitch together their own story. The reader can create her own beginning, middle and end while reading About Trees.

But this “lack of context” is something that I struggle with all the time. I think ambiguity is important and vital to the mystery and reality of everything around us. But then again, I don’t want to be vague and empty. I think there might be cracks between how things are supposed to be done in the “real” world and how they could be in the actual world that I experience and live in. For example, when I was working on the Tree Museum (a public art project commissioned by the NYC Dept. of Parks and Recreation, the Bronx Museum, and Wave Hill to celebrate the 2009 centennial of the Grand Concourse), I discovered that you’re not supposed to climb trees in city parks. It’s actually illegal to climb trees and you can get fined. I grew up climbing trees. I wanted to take kids out of the classroom and climb trees, but we couldn’t. I can’t imagine a world, this “real” world we’ve created, where the most basic things are “wrong.” Anyway, I seem to slip into some of those cracks. I don’t do what I probably should be doing if I was properly engaging with that day-to-day reality of working 9 to 5. I just work all the time, in my own way, in this other reality where humans aren’t at the center of things. We’re just another animal (but unlike most of the others, we’re destroying our habitat). “Crack in the Real” was the title of my last solo show (at VAN HORN in Düsseldorf in 2013). I borrowed it from Timothy Morton.

It could also be that what About Trees is, is actually so simple that I didn’t want to write it down and put it out there in public. For me, it’s about everything, about humanity, our knowledge and our understanding of and relationship with the things around us. I feel like this is volume one of a potentially infinite series. A futile attempt at cataloging everything. Like a home-brew version of the OED or the Encyclopedia Britannica.

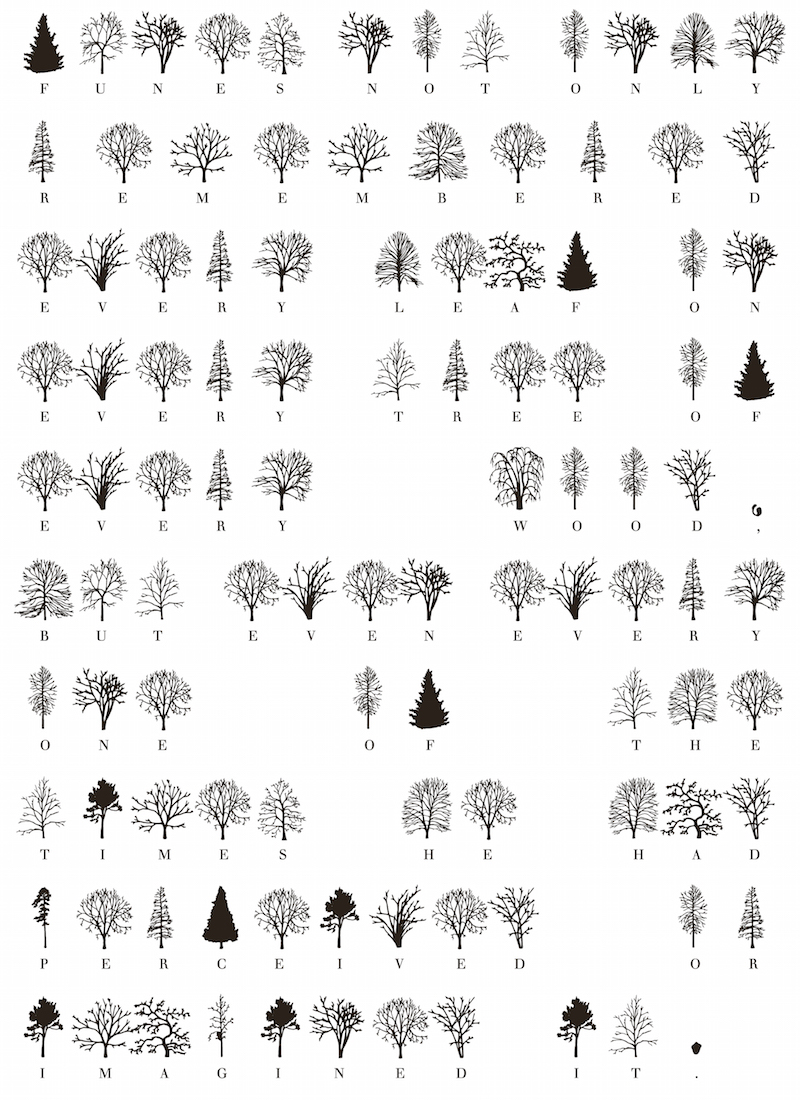

SS: Borges’ “Funes the Memorious” is sort of a connective tissue in the book. How does the excerpt relate to your idea of About Trees being a single volume in a potentially infinite series?

KH: Poor Funes, he’s doomed to remember forever. Borges’ infinite library is lodged in a tiny part of my brain and won’t go away, I see it everywhere. It’s so perfect, so pure. I was actually going to include his short story “The Book of Sand” (1975) about the infinite book. (1975 is an invisible thread running through About Trees.) But at one point it looked like all the texts were going to be translated letter by letter into the Trees typeface, so I was seriously trying to limit the word count (as we were looking at a book with 400 pages of trees!). I realized that with Borges one sentence could, potentially, sum up everything. One sentence from Funes is included three times (each time in a different translation), appearing at the beginning, middle and end of the book. As if the book is a solid, complete entity. But, for me, it implies the opposite as well—the book is potentially infinite and Funes will get translated over and over and over. Or the book is just one within an infinite series of books, within an infinite library. It goes on and on…

A sentence from Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “Funes el memorioso” typeset in Trees.

A sentence from Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “Funes el memorioso” typeset in Trees.

SS: While our alphabet can be translated into your alphabet of trees—and words and paragraphs turned into whole forests—it seems daunting if not impossible to translate the forest back into words. I see in this the beautiful and unsettling incommensurability of any object we’re attempting to know and put into words. Do you agree with this reading?

KH: That’s a nice word. Incommensurability. Yes, I think that’s a fair reading.

SS: Do you take solace in that incommensurability?

KH: No, I don’t think so. I just love how things are. Things naturally want to fall into these positions, into impossibly irrational and beautiful states, as if there’s an underlying rule or mathematics to it all. I wouldn’t say I take solace in that necessarily, but I’m fascinated and charmed by it. I wanted to be a physicist when I was little. It was James Gleick’s fault. Those beautiful books he wrote about Richard Feynman and Chaos. Like Feynman I wanted to study all those tiny, invisible things that make up the world around us. To understand how things work and how everything’s connected. When he was little he noticed that spaghetti breaks into three pieces and he figured out why and how. That blew my little mind. But, I knew I couldn’t play the bongos (Feynman was famously fierce) and it slowly dawned on me that I couldn’t play physics either. My brain just isn’t wired that way. I do try to follow what’s going on in science and read more books and articles about it than about art. Last year I studied Complexity in a MOOC offered by the Santa Fe Institute. Complex systems is a fascinating subject.

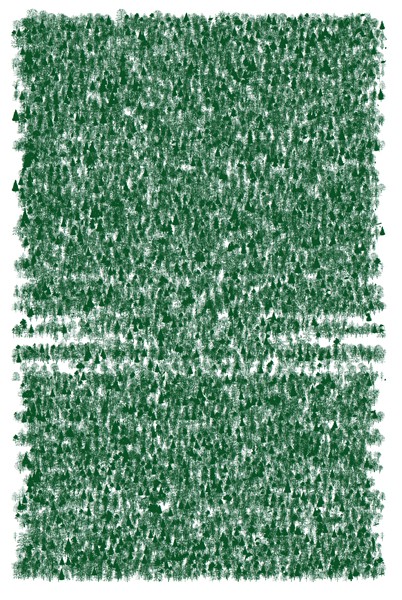

SS: And the density of the Trees typeface, as it is laid upon the page, reflects this complexity.

KH: It was very important for me that Trees be simultaneously legible and illegible. Or at least create a sense of illegibility. It had to be both logical and translatable while simultaneously being difficult, even impossible, to “read.” It had to be beautiful and “understandable” to us humans, but it needed to be inherently unreadable, or at least difficult to crack the code. It had to make us (or at least the reader), confront the fact that we can’t really “read” anything. We can’t really “understand” everything. We can name something and write it down, but what does that mean?

It had to make us (or at least the reader), confront the fact that we can’t really “read” anything. We can’t really “understand” everything. We can name something and write it down, but what does that mean?

SS: So it’s not so much about the gulf between us and the natural world?

KH: It’s not about incommensurability, or at least that’s not where I was (consciously) coming from. One of the reasons I had to make the alphabet, the typeface, and the book was because I feel like we (or at least I) have lost sense, lost grip, of reality. Language is broken. It’s become almost like a code and it’s acceptable to use words mindlessly. It’s frustrating to see how words like ” nature,” “landscape,” “environment,” and “earth” are being used. All these art-historical terms—what do they mean today and how are they being used and misused? A tree is a tree is a tree is a tree. Wait a minute, what are you saying? It’s as if the words and letters have become invisible. We’re so used to seeing them, we don’t think about them at all. Everything’s taken for granted. These days everything is “green.” Nature is… what, exactly? And landscape? Wilderness? Environment? All these terms have become meaningless.

I wanted to see what happens when you replace those most basic building blocks of language—the letters—with something else. What if we could use the very “nature” that we don’t/can’t understand to speak for us? What if we took one of the most basic forms in nature—the tree—to create a new alphabet? Would we see things differently? Would we be able to “read” things differently? Would we somehow be able to fix language?

Robert Sullivan’s essay “Liberty Trees” typeset in Trees.

Robert Sullivan’s essay “Liberty Trees” typeset in Trees.

SS: The idea that there is a language in or of things is of course an ancient one—reading auguries and divining portents in the natural world—was this at all a part of your thinking at all?

KH: Yes and no. It’s something I never dwell on. Lothar Baumgarten happened to come over to the loft the day I was working on the final, final edit and he saw the book dummy. We talked for a while about trees and these unseen things that exist beyond our daily comprehension. At home we have a lot of windows, but there’s only one living, non-man-made, thing visible outside—a little street tree that was planted about a year ago. We contemplated it and he mentioned how he communicates with trees… He promised me a text for volume two.

SS: The critic Viktor Shklovsky famously argued that one of the jobs of literature was to “defamiliarize” common things in order to enhance our perception of them. About Trees, I think, does this in two ways: by bringing to light the inherent strangeness and artificiality of nature and by placing the natural world in a new context. Do you hope for such a defamiliarization?

KH: Yes. That’s definitely something that I was interested in. I think there’s a complacency in our relationship with language, at least within the day-to-day corporate reality. Words are taken for granted. When I was in Mexico City I noticed the subway stops have symbols. When I asked I was told it’s because many people are illiterate, so a visual sign is needed. They’re simple, graphic representations of the places. I love that.

SS: One of the unifying thematic elements in the anthology concerns trees as (to borrow a phrase) “great archivists.” What is it about this characteristic that appeals to you?

KH: The invisible, all that we cannot see, is very attractive to me. We can only “see” a tiny fraction of what’s actually going on around us. It’s like whale song—it’s there, but we can’t hear it until we adjust the frequency. Or dark matter; apparently 99 percent of everything out there is made up of it, but we can’t sense it at all. We’re only aware of a tiny fraction of what’s actually going on around us, but we presume that that tiny fraction is the sum total of “reality.”

One of the simplest, most tangible, symbols of this is tree rings. We all know what they look like and, more-or-less, what they mean and represent. Each ring is a year. The different thicknesses correspond to happy or sad years for the tree. I used tree rings as the logo for the Tree Museum. Trees literally make visible their life story in the tree rings. We use trees to make paper and print books that contain our life stories. The infinite library… Matter becomes matter. Nothing from nothing…

SS: Moving outward from your specific concerns to a bigger question, I’d like to know what you think of the role of the artist in the Anthropocene?

KH: I’ve been thinking about this—art’s role, my role, in the Anthropocene—a great deal over the last few years. You could say it’s maybe the only thing I’ve been thinking about. I see everything as being connected to this question. I’ve become one of those boring people who just talks in circles about the same things over and over and over again. My boyfriend Dillon and I have been having this circular conversation for years (about art, economics, environment, politics, aesthetics, macroeconomics, ecology, policy, ethics, art…) so finally this winter we invited others to join us in our spiraling ruminations. Friends and colleagues and strangers came to our home for a series of salons on Sunday afternoons. We were specifically interested in looking at the discourse around the Anthropocene and exploring the possibilities for art and activism. It’s been fascinating.

A precursor to the salons was a panel discussion I was invited to attend a few years ago with Daniel Smith and Robert Sullivan. The conversation was organized to follow up on Dan’s article in the New York Times magazine “Is There an Ecological Unconscious?” In it Dan meets Glenn Albrecht and introduces a term he coined: solastalgia. Essentially, it’s homesickness felt by people who are at home. But their home, their environment, their landscape, has been changed so profoundly that it’s not really their home anymore. That’s the state I think we’re all in now at this point. How do we come to terms with this mind-blowing situation that we’ve put ourselves in?

SS: It’s been a year since our conversation. The first volume sold out immediately and the second will soon be available. How are you feeling about this?

KH: I’m thrilled that About Trees is available again. We’d hoped that we were making a beautiful and timely book, but we didn’t expect it to sell out so quickly! From the beginning it seemed to excite people. That was extremely gratifying—to make something useful that so many people wanted. It definitely seemed like it was filling a gap, creating a space for people to have conversations about many different things, including trees of course.

Can I tell you a secret? I’d hoped that I’d have the second volume of About Trees ready by now, so I feel like I’ve let people down by just producing the first volume again. It’s been almost a year (to the day) since I made it. I can’t believe it—what extraordinary times, with so many unprecedented changes. We had problems a year ago—that’s why I felt the need to make this particular book—but who could have foreseen what’s happened since: the trauma of Brexit, #BlackLivesMatter, the US presidential campaign and the increasingly alarming climate data and extinction events.

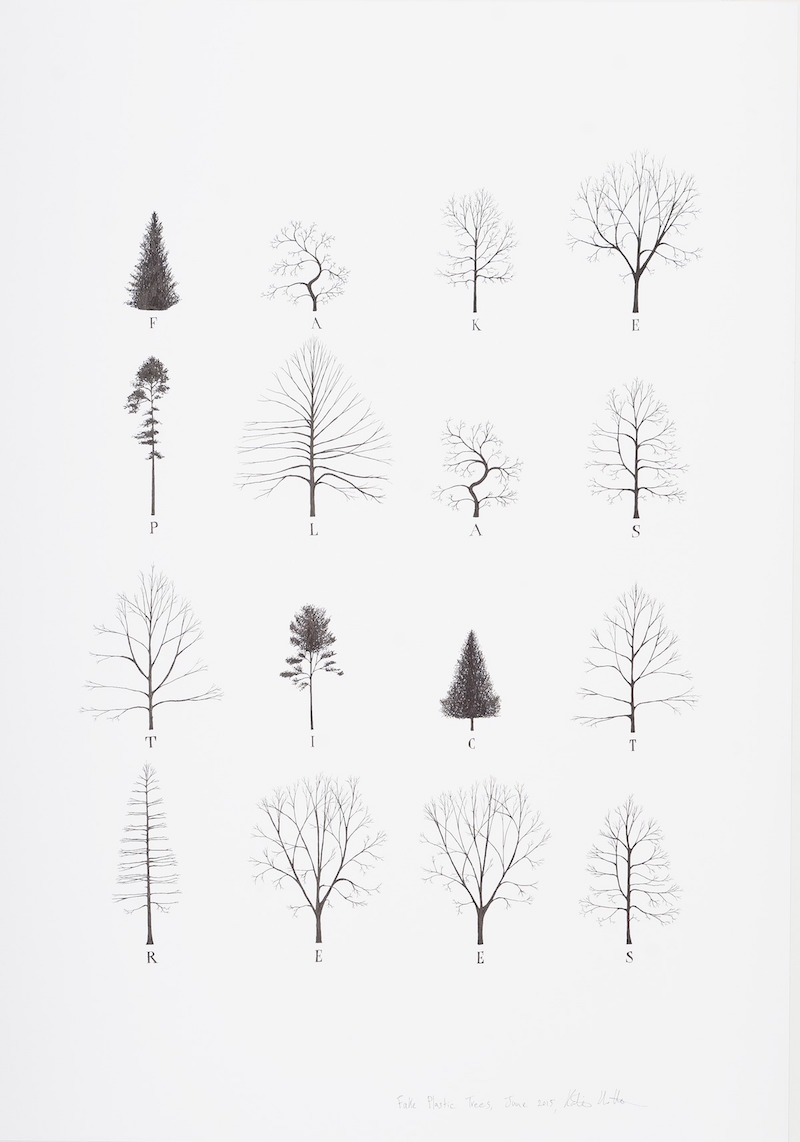

People have asked me how I selected texts for the book. Everything that I included had to deal (or at least had to help me deal) with these issues that I’ve been grappling with. For example, Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees” is included as a lament for the “fake plastic earth” and “fake plastic love”… It’s exhausting, on so many levels, to deal daily with so much unnatural catastrophe.

It wears her out

It wears her out

It wears her out

It wears her out

Extraordinary times. I’d like to think that About Trees is still timely and hopefully it’s still extraordinary.

Katie Holten, Fake Plastic Trees, 2015, ink on paper, 100 x 70cm.

Katie Holten, Fake Plastic Trees, 2015, ink on paper, 100 x 70cm.

All images courtesy of Katie Holten © 2016.