On Patrick White, Australia’s Great Unread Novelist

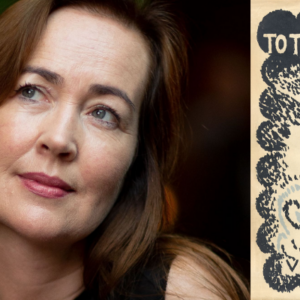

Madeleine Watts Wonders If Any of Us Can Go Home Again

When I was 22 I was in love with a man who had a framed photograph of Patrick White hanging above his bed. I had grown up with my father’s used copies of White’s novels, and had studied some of those books in university, but it was not until I found myself waking up beneath the dark glower of Australia’s only Nobel Laureate in Literature that I took a real interest in the author and his works. One morning I left the bed of the man who had hung White’s photograph and walked to a used bookstore on Glebe Point Road, Sydney where I bought the 1955 novel, The Tree of Man. It changed everything.

At that time, my university degree completed, I worked on the phones in a call center for the country’s emergency services. We were not allowed to read or even watch television while we were on the phones, but during the week that I read The Tree of Man I smuggled it in to the call center hidden inside my headset case. I read between calls for car crashes and domestic abuse. I carried the novel into bathrooms and bars. I read it while walking home. I couldn’t stop reading. I was miserable and lovesick and didn’t know what I was doing with my life, and whether or not it was those circumstances I needed to bring me to Patrick White, I can tell you that The Tree of Man snatched me into a passion that has afflicted me ever since.

The Tree of Man isn’t about much—a man arrives with his dog on a scrap of land on the edge of Sydney, and decides to stay. He marries a woman. They have children. The man and the woman love one another quietly and fearfully, and treat one another terribly and well, and then die. I underlined whole pages. The novel felt to me as though it contained the entire breadth and depth of life. It was also absolutely Australian. White delivered to me my country and my city in a way I had not recognized before I saw it in his words. The Tree of Man gave me a blueprint for what an Australian writer could do with their Australianness, and then, two months later, I left Sydney and moved to America. I did not go home again for five years.

*

In 1953, Patrick White published an essay called The Prodigal Son. The essay described the reasons why, after many years of living in London, he had made the decision to return to Sydney in 1947. White remembered an Australian journalist in London, who once asked him whether he wanted to go home. “I had just ‘arrived’; who was I to want to go back? ‘Ah, but when you do,’ he persisted, ‘the colours will come flooding back onto your palette.’” White explains that indeed the colors did flood back when he went home. “Writing, which had meant the practice of an art by a polished mind in civilized surroundings, became a struggle to create completely fresh forms out of the rocks and sticks of words. I began to see things for the first time.”

The decision to return to Australia when all the other writers were leaving is at the heart of all of White’s novels. Raised in Sydney’s well-to-do Rushcutter’s Bay, White was sent to England at 13. He attended boarding school, then Cambridge, and during the war was stationed in North Africa. It was there, in 1941, that White met Manoly Lascaris, the Greek officer who he would love for the rest of his life. By the time White and Lascaris returned to Australia in 1947 White had written three tepidly received novels, and a play. It took coming home to Sydney to transform his writing and elevate it to the level of genius. White produced The Tree of Man, in 1955, his first novel to be written in Sydney. He went on to write a string of masterpieces in quick succession: Voss, Riders in the Chariot, The Vivisector. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973. The Nobel committee credited White “for an epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature.”

He became a literary icon, but White knew that people rarely actually read his work. He professed not to care what people thought, but he would sometimes check for copies of his novels in local libraries. He would search for dog-ears and stains, to gauge how far in the book they had read. Most people, he deduced, never finished. The Australian reading public never quite warmed to White, and nothing much has changed. My grandmother “couldn’t stand him.” I have seen my mother take up one of his novels—The Solid Mandala—and after a few moments quite literally toss it aside. White’s books are metaphysical, lyrical, high modernist, full of baroque descriptions of landscapes, and unsparing in his examination of the people who live in them. For a country besotted with kitchen-sink realism and plain-speaking larrikins, Patrick White was baffling.

In 2006, the Weekend Australian newspaper conducted an experiment. They submitted chapter three of The Eye of the Storm (1973) to twelve publishers and agents around Australia under an anagram of White’s name, Wraith Picket. Nobody offered to publish the book. One responded, “the sample chapter, while reply (sic) with energy and feeling, does not give evidence that the work is yet of a publishable quality.” Notwithstanding that the chapter was not White’s finest writing, and the unfairness of submitting a chapter out of narrative sequence, the hoax prompted a minor crisis in Australian literature: if the industry couldn’t recognize the greatness of our sole Nobel winner, how unenlightened must the country’s publishing industry be now? Shortly thereafter, the ABC launched an online portal called Why Bother With Patrick White? The portal always struck me as sad. What other major writer would need a website dedicated to convincing his countrymen to give him another go? The link to the website is dead now. It would seem, in the end, that nobody could be bothered with Patrick White.

They were lean years when the men ate garden snails and drank cooking sherry, years when they were mostly happy.

In some respects this reflects a national pathology. Unlike an American or British child, an Australian student can go through thirteen years of education without reading much of their country’s literature at all (of the more than twenty writers I studied in high school, only two were Australian). This is symptomatic of the country’s famed “cultural cringe,” a term first coined in the 1940s by the critic A.A. Phillips to describe the ways that Australians tend to be prejudiced against home-grown art and ideas in favor of those imported from the UK and America. Australia’s attitude to the arts has, for much of the last two centuries, been moral. “What these idiots didn’t realize about White was that he was the most powerful spruiker for morality that anybody was going to read in an Australian work,” argued David Marr, White’s biographer, during a talk at the Wheeler Centre in 2013. “And here were these petty little would-be moral tyrants whinging about this man whose greatest message about this country in the end was that we are an unprincipled people.”

But if White could critique the country and name Australians as unprincipled, it was something he had earned by going back.

*

At the end of 2018 I went home for the first time in five years. I returned to Sydney for three weeks. The idea of “going home” was so strange after so long that I felt I had to give myself a distraction. And so I decided that I would visit the houses of Patrick White. I would pay tribute, I explained to anybody who asked. What I was doing, in reality, was trying to gather up the Sydney in my mind and map it on to the changed Sydney of the present.

What was it like to return to Sydney after five years? Well, it was like the colors came flooding back onto my palette. I was overwhelmed by the city’s wildness. The tremendous heat followed by operatic thunderstorms. The cacophony of birds. The high skies. It felt like my natural habitat.

Home is not just the physical structure which houses us, but a landscape and a territory, a feeling for a place. Bernd Heinrich argues that this feeling is in large part one of instinct. Home is not only the house where we live, but includes the “surrounding territory that supports us. Homing is migrating to and identifying a suitable area for living and reproducing and making it fit our needs, and the orienting ability to return to our own good place if we are displaced from it.” And so it was disconcerting to find that, walking around Sydney in December of 2018, I felt displaced.

What I was feeling was unhomed. The smells and the sounds were the same, maybe, but Sydney looked radically different to when I had left it. Newspapers were forever talking about the housing bubble, and whether it was on the verge of bursting. Homelessness had spiked. People my age had been priced out of the inner-city, pushed further out west. Yet there was development everywhere. Cookie-cutter gray apartment buildings were going up all over the city, erasing the landscape of old warehouses and disused railway track. My paternal grandmother’s former duplex on Anzac Parade had been developed into a new lavender-colored apartment block. The house my maternal grandparents built in 1970s Strathfield had been demolished as well, replaced with an ugly, energy-inefficient McMansion. The crumbling terrace where I had lived in my early twenties had been renovated, painted and sold. The pubs I used to drink in and the cafes where I used to get coffee the morning after, closed. The man I used to love had moved out of the bedroom where he hung the portrait of Patrick White, and into a broken-down house in the unfashionable neighborhood where I grew up.

The issue of home is a vexed one in Australia, as it is in every country forged through the project of British imperialism. I grew up understanding that my ancestors’ tenancy on the land had lasted no longer than two hundred years, and was of questionable legitimacy. But it was only after I left Sydney that I became increasingly preoccupied with the idea of home. Home is, in the words of T.H White, “an anchorage.” You can travel far and wide with no fear, if you’d like to, knowing you have something to pull you back from permanent limbo. But when I left Australia I trashed all my anchors. I sunk every boat that I thought might sink. After five years, the move away felt irrevocable. I was a legal permanent resident in America, and whether or not I stayed in the US, or moved somewhere else eventually, I felt and still feel like an immigrant who will never go back. Returning to Sydney only strengthened the feeling. I had come home to find it looked and felt nothing like my home.

I knew that Patrick White had lived in three different houses in the city of Sydney, and yet I had no idea where they were. I had never visited when I was growing up. They were none of them museums or monuments. And I wondered what it would be like, to visit them now, in a Sydney of my own imagining, a city formed in my mind by the words in his books.

*

Patrick White spent his childhood in a house called Lulworth in an eastern harbor-side neighborhood built by and for the rich. “Life in the wealthy east went on as though Mayfair were but a short drive from Darling Point,” observed Sydney writer Ruth Park. It was Lulworth, a few days before Christmas, which I visited first.

I took the train to Kings Cross. The city’s long-lived red light district, it has always been the location of backpacker hostels and bad nightclubs. It was the sort of place where I could have my drink spiked and black out in the middle of the street. But like everything else, Kings Cross had changed. As I walked along the main strip, I found that nearly all the nightclubs had shuttered in my absence. There were dog grooming parlors now, and supermarkets where you could buy heirloom tomatoes and dukkah.

The approach to White’s childhood home took me down the warren of higgledy-piggledy streets behind the Cross. The nursing home that has absorbed the house stretched around the curve of the magnolia-soaked road. White lived at Lulworth through his childhood until he was thirteen. The house was bought by St Luke’s Hospital in 1938, and shortly transitioned into an aged care facility. St Luke’s houses former judges, lawyers, and academics in the last stages of their life when infirmity, dementia and Alzheimer’s have taken a toll. Neville Wran, the former New South Wales premier, spent his last days at St. Luke’s, as did the former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. A 2014 article in The Australian quoted one anonymous insider, describing Lulworth as an “elite club” for the citizens of the eastern suburbs: “You go to school at Ascham or Cranbrook, you get married at St. Mark’s, and when you get old you go to Lulworth.”[/pullquote]

After working on the farm all day, White would come in around five and begin to drink heavily. He would eat, and then at nine o’clock fall asleep for a few hours. At midnight he would wake up and write until dawn.The word “Lulworth” was still visible in the old stone gate, but St. Luke’s has been built around White’s childhood home like a fortress. Through the gate I could see up the driveway and through to the old house that lay at the center of the compound, quite small among the towering hospital facilities. Below my feet the rush of water in a stormwater drain testified to what remained true about the property—everything about it was wet. The wetness of Lulworth prompted the growth of a spectacular garden, one that populated nearly all of White’s writing about Sydney. In the garden, which White likened to one painted by Henri Rousseau, he spent long periods of time looking out to the harbor, down the stretch of overgrown land which is today blocked by the high-rises which have reclaimed the view for themselves.

Too nervous to ask if I could look inside, I took the snaking street down the hill, to the park on Sydney Harbor. At the Yacht Club of Australia a screen had been mounted, live-streaming the cricket right over the bay. Boats clanked together on the water. Men fished in full sun along the foreshore, disregarding the signs warning of wastewater overflow, and forbidding both fishing and the paddling of dogs. I lay down beneath a paperbark tree and watched the paddling of a dog. The heat was incredible.

The radios and televisions that week were full of total fire bans and dangerous heat warnings. In a month’s time much of the countryside around Sydney would be an inferno. Heat records would be broken all over the country. Bluebottle jellyfish would sting more than 5,000 people on the Queensland coast, and hundreds of dead fish would rise to the surface of the Darling River. According to my mother, the summers had been getting more hellish every year. The summer of 2017 and ‘18 had been so hot that it had prompted her to install air conditioning, after I had spent my childhood sweating to sleep in the path of a standing fan in a house of sun-baked bricks. The heat had been so great that the city’s bats dropped dead from the sky. Residents had woken up one morning to find thousands of carcasses on the ground, and yet more bats, dead but still clinging to the trees, gradually decomposing and falling from the branches as time crept on.

In the Sydney I had grown up in, bats did not fall to the ground in the heat. The fish did not die en masse in the rivers. We did not need air conditioning.

On the edge of the park that afternoon there was a beautiful, old cricket pitch, the grass a vibrant green. As I walked back towards the Kings Cross train station, I stood and watched the sprinklers circle. During my childhood, sprinklers like these were banned for household use. I grew up in drought conditions. Since my return to Sydney all anybody could talk about was the worsening of the drought, the failing of the farms inland, the gradual depletion of the city’s reservoirs, and the emergency re-opening of the desalination plants. And yet the sprinklers were turned on at full-blast.

Anyone raised in Sydney is attuned to this illogic: the dams might dip and the plains yellow and die, but the Harbor-side cricket pitches must by rights be kept green. It was only now that the greening of the cricket pitches struck me as so ominous, an Anthropocene allegory, like the violinists who kept fiddling as the Titanic went down.

*

On the drive to Castle Hill, my mother told me the story of how Patrick White almost cost her a university degree. It was 1976, and her grade twelve class had been assigned White’s 1957 novel, Voss. But my mother’s English teacher never got around to reading Voss, despite it being part of the state curriculum at the time. The man just couldn’t get through it. The book was long and it was difficult. The teacher assured the class they wouldn’t really need it for the exam. But they did. My mother scraped through only by piecing together some half-baked observations on Jane Austen’s Persuasion, and she was the only person in her class not to fail English.

By the end of Patrick White’s life, he was sick of Voss too. Writing to a friend in 1981, he opined, “I’m a dated novelist, whom hardly anyone reads, or if they do, most of them don’t understand what I am on about. Certainly I wish I’d never written Voss, which is going to be everybody’s albatross.”

Voss has become a touchstone of White’s inaccessibility. Whenever I talk to people about Patrick White in America, I’m likely to be told that they’ve tried Voss, and couldn’t get through it, if they’ve heard of him at all. “There are better books,” I try to explain, but most of them are all out of print, including The Tree of Man.

Dogwoods was the name of the house in Castle Hill where Patrick White lived from 1949 to 1964, when he returned home to Sydney from Europe. If the Sydney of White’s youth had been monied, damp and genteel, Castle Hill was barely Sydney at all. Just farms. After the Second World War, when White and Lascaris moved in, Castle Hill was declared a Green Belt and divided up into allotments The farms were weekend hobbies for most people, who were waiting for the day when the district could be cut up into building blocks for fibro houses and the westward-spreading gut of Sydney’s suburban sprawl. But when White and Lascaris moved in, they put all their effort into farming.

“I am sure I have been right in returning to the land,” White wrote to a friend after he and Lascaris purchased the house. The men planted the paddock with vegetables and flowers, which Lascaris took to sell at the markets every week. They raised chickens and dogs, and made their own butter. Nobody paid much attention to Lascaris and White other than to wonder at their farming so earnestly. Sometimes White attracted attention by wearing a beret down at the shops, but in 1950s Sydney that didn’t suggest the affectations of an artist so much as somebody who had served in a tank regiment. They were lean years when the men ate garden snails and drank cooking sherry, years when they were mostly happy.

It was at Dogwoods that White wrote The Tree of Man. It took several years of living back in Australia, and finding faith in God, for him to begin to write again. Once he had started the novel absorbed him for two and a half years. After working on the farm all day, White would come in around five and begin to drink heavily. He would eat, and then at nine o’clock fall asleep for a few hours. At midnight he would wake up and write until dawn. His asthma exacerbated by damp weather and stress, he often wheezed through the night, or took to his bed. He treated Lascaris terribly, who nonetheless bore White’s rages. “He has a genius,” Lascaris said. “Even he doesn’t know where it comes from, but he obeys it. If he needs to rage, I am there, and he knows I will forgive him. It is very painful, but I do forgive him.”

The drive to Castle Hill took an hour along the M4, past car yards, office supply stores, and billboards hovering over the freeway, paid for by the billionaire nationalist Clive Palmer, imploring you to “Put Australia First.” Castle Hill is one of the fastest-growing parts of the city. A small stadium of a train station was under construction in the suburb’s center, which—the notices tied to the hurricane wire claimed—would take 12,000 cars off the road in peak hour. Orange-brick apartment blocks encroached upon the gothic houses that were once the center of vast rural properties. White’s old house, “a bit of Strathfield in a paddock,” was on Showground Road, a four-lane street dense with new developments and thick with traffic. The storms of the days before had felled trees and power lines. Cicadas screeched. The Insurance Council of Australia had that morning classified the storms as a catastrophe.

Once the centrepiece among six acres of farmland, the surrounding land of White and Lacaris’s Dogwoods has been sold off since the 1960s, leaving only the house. Heritage-listed after White won the Nobel Prize, the house has been used as a family legal practice since 1993. I was told I was free to wander around the building.

“It’s the original fireplaces and everything,” one of the lawyers told me. “You can see that unfortunately the underground train line has caused a bit of foundation movement,” she continued, and pointed to the cracks in the plaster that veined the walls. Three days before Christmas, it was the last day the offices would be open for the year, and the lawyers were clearing out early.

I was shown to the back of the house, to a small room off the main open-plan office. “This is where he used to write,” I was told. The room was dark, but a window looked out over the garden. It had been filled with office supplies, a television, a stepladder, and boxed Christmas decorations. The plaster walls had cracked, the room smelled musty, the concrete floor made the room strangely cold. A door by the old office opened out onto the backyard and the old veranda where White spent much of his time. I opened it. A kookaburra laughed. The grass was studded with mushrooms and toadstools. When White was writing The Tree of Man, he would have been able to see all the way down through wide land to his orchards and the creek, not the fence and the carport that are there now. I stood in the doorway for a long time. Wondering why it was that White had needed to come to this house, to this very room, to write. Wondering whether I had made a mistake in leaving. And whether I loved The Tree of Man in part because it made a mockery of my own decisions?

After the Second World War, and in the wake of a housing crisis, Heidegger delivered a lecture titled “Building Dwelling Thinking.” He argued that people had lost their ability to feel at home in the world. Globalization, migration, and mobility not only dissolved the connection between people and the places they lived in, but created a kind of psychological unhoming as well. His description of mass-homelessness had a darker undercurrent, one that had been embraced by the Nazis, who saw home and the “homeland” as the only legitimate source of identity. In Heidegger’s hands home became an ideological bludgeon, one used to justify the expansion of national borders, to separate those who belonged and eject or murder those who they perceived did not. After the war, and at the beginning of the era of globalization and migration that is with us still, he was preaching the same gospel. Wouldn’t we all be better off staying where we belonged, going back to where we came from?

“Have you read White’s books,” asked one of the solicitors in the practice. I told her that I had. “Apparently they’re a bit… out there. Is that right? I’m not a reader.”

I allowed that Patrick White could be heavy-going.

“Dark, almost?”

“No, not really dark.”

“I heard he was a manic depressive. Although there’s nothing wrong with that.”

Patrick White was not mentally ill, although he did once tell a crowd at the Henry Lawson Festival of the Arts that the artist’s soul was lonely, manic-depressive, and inclined to alcoholism “to wring out the ultimate meaning.”

“We’ve heard some weird and wonderful things,” continued the solicitor. “I think he was quite eccentric. I’ve heard he used to have an Italian lover who he kept locked up in a back cage, and he’d be let out on a leash. That’s how manic Patrick White was.”

“A cage like for an animal?”

“Correct. Because I think they were into some weird stuff. But then again, to be able to write the books that he obviously did he must have been quite eccentric.”

I was not sure how to respond to all of this. The “lover,” she was referring to was Manoly Lascaris. He was Greek, not Italian. I can find no evidence to suggest he was ever, let alone regularly, locked in a cage at the back of the house on Showground Road.

That this was the kind of story I was being told seemed like something I should have expected. It wasn’t simply homophobic or xenophobic or cheap gossip, it was unbearably Australian. These weird men, one an immigrant, one insane, writing “dark” books out on the edge of the city. How peculiar. To this kind of thinking White returned in 1948, and it’s still there, still plaguing his legacy.

*

On the day before I flew back to New York, I made my final pilgrimage, to Centennial Park and the house where White lived on Martin Road. This house, the one in which he died in September 1990, is the only one of the three houses with a plaque. Centennial Park contains the largest public park in the city, and its houses constitute one of the most expensive neighborhoods in Sydney.

Centennial Park is quiet, and vast, and beautiful, bordered by Moreton Bay figs and Norfolk Island pines. The morning was smothering. I progressed down Martin Road. The driveways were filled with Jaguars and basketball hoops, the high wrought-iron gates flanked by intercom systems and cameras. Set back from the street, White’s house rose up a set of steps above the road. A eucalyptus tree had grown and twisted so that a large branch the size of a fat man’s arm blocked the front path at about four feet from the ground. If you lived in the house, you would never enter through the front door from the street. After a few moments I pressed the buzzer. Nobody answered. I pressed it again. Still nothing. It was a few days after Christmas, and people had left town. I had hoped I might be able to just walk in. Instead I looked up at the house for a long time, and then walked away. I don’t know what I was expecting. Some kind of comfort.

“Once you’ve left, for whatever reason, and stayed away, there can be no going back” writes New Zealand-born and Scotland-residing writer Kirsty Gunn. “Not later, not ever, not really. Self-consciousness has leapt up in the space between one shore and another and created another person for ourselves in the gap.” I had been trying to gather up the Sydney in my mind and map it on to the changed Sydney of the present. But places don’t work like that, and neither do we. That’s why the things that had the most emotional resonance, what I kept talking about after I returned to New York, were environmental. The quality of light. Cicadas. Mangos. Lorikeets in my mother’s garden in the morning. Smoke in the air.

After my return I read about the fires obsessively. I read about the fish die-off in the Darling River and the bluebottles in Queensland and heat records broken all over Australia. I panicked. I have lost the person I was when I left, become, as Gunn says, another person in the gap between there and wherever I go now. But the landscape and the climate of my home have already changed. One day, in my lifetime, they might be gone for good, swallowed by rising seas and increasingly extreme weather patterns, until the city is not there at all. Not like I remember it.

We will all one day be looking to come home, and finding that it’s not there anymore, whether we left it or not. We are all immigrants now.

I found an entrance to Centennial Park, and walked along the fence until I found myself opposite White’s house, looking at it from the other side of the railings. I stood beneath the pines he had seen from his windows every day until his death. The ground beneath my feet was all sand dunes and scrub grass. I lay down. The heat beat down and it was completely quiet and not a single other person was in sight. I spread out my arms. I lay in the park for a long time, engulfed by the sand beneath the pines, feeling at once as though this was precisely where I belonged, and entirely unhomed.

“In the end there were the trees,” wrote White in the final pages of The Tree of Man. And so what, he asks, should a person do? “He would write a poem of life, of all life, of what he did not know, but knew.”

Madeleine Watts

Madeleine Watts is the author of The Inland Sea, which was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award and the UTS Glenda Adams Award for New Writing. Her novella, Afraid of Waking It was awarded the Griffith Review Novella Prize. Her nonfiction has been published extensively in Harper’s Magazine, The Guardian, The Believer, The Paris Review Daily, Literary Hub, and Astra Magazine. She has an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University and teaches at Columbia and Johns Hopkins Universities. Her latest novel, Elegy Southwest, is available now from Simon & Schuster.