On Not Writing, and Letting Wildness Be Your Guide

Leila Chatti Wrestles With the Daily Idea of Being a Writer

For years I felt very bad. There were reasons for it. When asked, as writers often are (at parties, in emails, to fill space), what I was working on, I answered, Nothing. This wasn’t true, but I felt it was. My project was to stay alive. Which required more effort than I could admit.

The despair began when I finished my first book. Or, rather, it resumed. The book had been something I could throw myself into entire. Writing was an interruption in suffering, a transformation of it; writing about my life gave me an escape from my life. Entering the poem as a method of leaving the room.¹

I was living in Wisconsin, a miserable place to live when you are prone to misery. In Wisconsin it is winter all the time. Even when the glassy lakes thaw back into water, there’s this coldness that lingers. It seeps inside. In deep. I think of that time, and a shiver runs through.

I had been brought to Wisconsin to write poems. When the first book closed itself—like a door, final, against me—I thought, Okay, I will write the next book. Then The Subjects rushed in. And I thought, No, not that book.

*

I don’t want to write the true book; it’s the one I want to write: I tear it from myself.²

I did not want to write that book, so I stopped writing. But the writing did not stop. It had its own mind, one inside mine.

I did not want to write about The Subjects. I wanted to write about pleasant things, like dogs. If I wrote poems about dogs, then it would be proof I was happy and well-adjusted. But there are certain subjects that, once they’re yours, force themselves to the front of the queue. And I did not have a dog. I have a cat, Sylvia, named after exactly whom you think.

Because I needed to be good, having failed to all day, in bed I would write. On my phone, in the dark. The least I could do was keep my failures organized.

I said I’d stopped writing—to you now, and to anyone who asked in those days. What I meant was I’d stopped writing the way I knew how to write, what I recognized as writing, the way I had always written. Before it had been simple, if not easy: I sat at my desk and unstoppered my mind and waited until everything I had to say emptied onto the page, and then the writing was done. It felt good to do it. But this was different—I didn’t want to say anything about The Subjects, anything at all. And yet, I had to write poems; poetry paid my rent.

I tried many ways to outrun what there was to say, to shove it down, to go around. But poems are cleverer than the people who write them. And your Subjects—like light, like water, in your hands—ultimately find an opening and slip through.

*

Night Poems

What you won’t say takes up space. Creates a block. I wanted to say something else, anything else, but the unsaid becomes a stone in the throat.

I believed I could only be a good person (worthy of love and my place on this earth) if I was a good poet, and I believed the way to be a good poet was to write a poem every day. My self-loathing was ouroboric—I felt terrible, so I could not write, and because I did not write, I felt terrible. Obediently I returned to my desk every morning and, all day, obediently I sat in my silence—like a child forced to sit in the mess she’s made, as punishment. I felt very bad. Then night.

Because I needed to be good, having failed to all day, in bed I would write. On my phone, in the dark. The least I could do was keep my failures organized: one document for each month (for instance, January 2018), in which I would scroll down to an empty space and write into it until I fell asleep. Unthinking (not with my daymind, the one of silence), on the threshold of dream. My only intention was to be accountable, to be good. But it wasn’t really writing, I told myself, and whatever had come of it was surely not a poem. Bad! Above each one the date, or else: Night Poem.

The next day, I vowed, would be different—I would write a real poem, a poem free of suffering, which would then break me free of suffering. Yet each night ended up the same: my finger brushing swiftly against the light so I would not see what, the night prior, my mind had said.

Years I would not look.

*

Divine

That others engaged in dream-near writing was not known to me then. I had never heard of automatism. I did not know of Jung’s most difficult experiment and had not intended to embark on my own. I wanted only to write. My nightself was porous. Exhaustion wore a hole in me through which the words emerged.

My project of staying alive is one passed down. Before me, my aunt and grandmother, and more women beyond.

I discovered, in time, other tricks. One was speed. I found that if I wrote very quickly I could get ahead of the censor, the self in me that guarded The Subjects and was terrified that, if I wrote anything at all, The Subjects might spill out. But this trick alone wouldn’t do. I couldn’t be trusted with freedom, with an infinite range of language (any authoritarian knows this is where the trouble lies). I created a leash and slipped it on. Tethered, at the other end, to a text not my own. Tugging me back. So I could never wander too far into the wilderness.

It worked like this: I would select a book by a poet I admired. Then I would flip very fast, back and forth, through its pages, so fast that my eye and mind could not keep up. I would do this until I snagged on something—not my eye or mind alone, but my whole self. It was a visceral feeling. (Poems are not written only by mind, but inescapably through body.) I recorded these encounters with the text—words, misreadings, associations—and proceeded on, with neither force nor objective. Eventually the poem would finish. On its own terms.

Someone, something gets into you, your hand is an executant, not of you, but of something. Who is it? What, through you, wants to exist.³

I came to understand this process as a sort of divining and called it such. As one wanders out into a field, rod in hand, ready for the twitch. I did not know what lay under the surface, but I went out looking, trusting something must be there.

*

Oracle

What, through you, wants to exist.

A child began in me and died in me. And another. And another. And I was, by this, wildly rearranged.

The year I turned thirty, 2020, the world upended—the shared one, and my own.

I began losing many things. My babies, and then my mind. Track of time and time itself. Touch. My hold on The Subjects, swollen now as a river after a season of heavy, heavy rain.

I have always put my faith in poetry, have come to it for answers. (I have never understood the shame, in poets, in admitting this.) And there was no one else, then, to turn to—the world closed, I lived inside a room of books. This is not metaphor.

Sequestered in my personal library, wildered by grief, I looked to the poets who had all my life guided me. Those women who, like oracles, spoke the true thing. Godmouthed. Who had seen what was and would be. And said it strange.

Oracle: from the Latin orare. To pray or to speak. Surely they lived as I did. Needing to write poems, in order to do both at the same time.

I approached their poems like the prophecies of oracles—something to be deciphered, the message cryptic. The oracle at Delphi was originally a girl, then later a woman over the age of fifty. Her title: Pythia. My mind sees this and instinctively reads it as code, rearranging its letters: Sylvia Plath. It was with her work I began, first woman poet I encountered on my way to becoming one. Poet who spoke the unsayable thoughts I could not name and had believed were mine alone.

Poet: from the Greek poietes. Maker.

I came back to her poems because I was failing. When my body could not create a child who survived my body, my mind could not create a poem that did. Grief unmakes. The world, the word. Because I approached it desperately, language fled from me. Language is like an animal, wary of fear. Say each word was a bird—alighting briefly, out of reach and then gone again. Or, when caught forcibly, it wrestled fiercely against my grip, then died from the strain of its efforts.

A woman who writes is a woman who dreams about children.4

The writing started with Plath’s poem “Childless Woman.” I took the title and the final word of each line. Womb, moon, go. I planted the words on the page and then more sprung up from the depths of me, to fill in the spaces. I wrote into the poem to discover what else it—I—had to say. To forge a way forward.

I continued like that, looking to unearth in poems the message beneath, because I needed there to be a message beneath. My mind sought a cipher. If an answer wasn’t clear, it wasn’t because an answer wasn’t there—surely one existed, in code, waiting to be unlocked. Broken. Language of transformation required transformation of language. It wasn’t that I garbled up the poems to make something incomprehensible; it was through these translations that I was able to approach what was wild in me and teach it to speak.

Some words were slippery. What is shadow’s shadow side? Is it light, or is it the body between?

One of these earliest codes was what I came to call the antipode. I took a poem and translated it, word by word, into its exact opposite as faithfully as I could. I became you, good was bad, day flipped to night. Trauma disorients. It turns what is known into what is unknown. It whelms the self. The world. Upends.

Some words were slippery. What is shadow’s shadow side? Is it light, or is it the body between? The antipodes revealed to me how I view what I view, my inner calculations. I developed a double sight—seeing through what was said to what was unsaid, seeing both at the same time. The words inside the word. The refracting lens of the self, translating world. Awful, full of awe.

Antipode: originally those who have their feet against our feet—inhabitants on the opposite side of the earth. My feet against the feet of another woman, against language, against the threshold of death. (One of my stipulations: all of the women whose poems I “translated” through code were women who had already passed into that other world, beyond.) Or myself pressed against my other self—my feet rooted in/against shadow. One standing in the world of consciousness, the other submerged. I imagine myself standing on a plane of ice sealing a lake, as a shadow presses, urgently, up, to shatter it from below.

Forms born from wildness, like dreams, create a space that is both totally free and totally limited. The disorder was so great that I required greater and greater order. When the brace of the Golden Shovel left too much flexibility for my comfort, I added another, creating the golden hinge: a form in which a borrowed line can be read horizontally as the first line of the poem as well as vertically down the left spine, as the first words of each line.

I wrote poems using only the words of another poem, the original text a word bank. When that wasn’t constraint enough, I layered on more form—a pantoum written using only the words of another poem, a ghazal. I tightened it further, writing poems in which each line was an anagram of the original poem’s corresponding line (my poem’s first line an anagram of the original poem’s first line, my poem’s second line an anagram of the original poem’s second line, etc.). Then I wrote a poem in which every line of the poem was an anagram of a single borrowed line, that borrowed line serving as its title.

Like this, during the worst of it, I learned to write again. My mind taking apart, then remaking. An ear pressed to the wall of the page. Down labyrinthine tunnels of pages, of words, of self. Until I came out the other side.

*

I speak of form, of lineage, how together these led me back to language, which led me back to living. But it is impossible to speak of lineage of the mind without speaking of lineage of the body and be speaking the truth.

I wanted to die. I say it plain because it is plain; it isn’t interesting. My project of staying alive is one passed down. Before me, my aunt and grandmother, and more women beyond. Disorder of the body disordered the mind. I was not the first to lose a baby, to be racked by her efforts toward one. Pattern is order and order is form. If I inherited this form, did I already know the steps to follow—did I already know the way to the end? The women in my family could never be oracles, dead long before fifty. Seers of no future.

Poetry without form is a fiction. But that there is a freedom in words is the larger fact, and in poetry, where formal restrictions can bear down heavily, it is important to remember the cage is never locked.5

Form can be a container for pain, but it must never be a prison of pain. If a form no longer suits, break it. Or create another. I can tell you this now: form’s gift is not in knowing the end. Form is instruction into greater mystery.

Suicide is the opposite of imagination. The creative impulse is an impulse against death. Inspiration: from the Latin, inspirare. To breathe. I never wanted to die—this is, of course, mistranslation. I wanted not death but less pain in my living. And whatever it promised, that vast silence, the desire to create was greater. Use the hum / of your wound.6 Pain made me turn to poetry, and poetry—the art of new seeing, of infinite possibility—returned me to world.

*

Do you know what I was, how I lived? You know what despair is; then

winter should have meaning for you.7

It is winter as I write this. I have taken breaks to hold my daughter, to nurse her in front of the window I keep unshaded so as to watch the snow. Snow is private. It convinces me I am invisible, though I am clearly seen.

In the years I did not write, I wrote a book. There were reasons. I needed to live, to make, to make a living. To heed the little bit of God in me, the part that creates. Cannot help but to. Thank God.

In time it became easier—my life and the writing of it, the two intertwined. I became braver. I could say things plain, without constraints to hold me. After thought, beyond the shadow. Some of The Subjects were named, which stilled the others.

Again it is winter. What is wild sleeps deep. There are stars of snow in the trees. A cloud rising, then vanishing, above my tea. The writing is done for now. Quiet, but not silent. Here in the room. The world. Milk shining on her cheek.

1. Adrienne Rich, “Shooting Script”

2. Hélène Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing

3. Marina Tsvetaeva, Art in the Light of Conscience; quoted in Hélène Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing

4. Hélène Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing

5. CD Wright, Cooling Time

6. Anne Carson, “First Chaldaic Oracle”

7. Louise Glück, “Snowdrops”

_________________________________

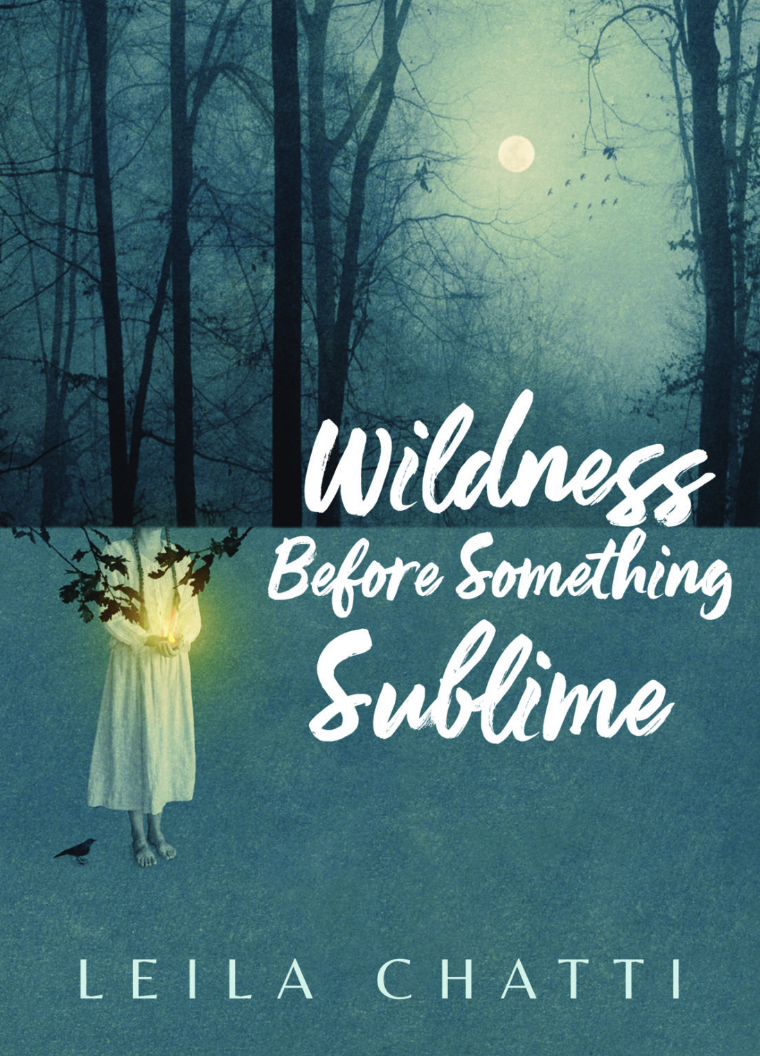

Leila Chatti’s Wildness Before Something Sublime is available now from Copper Canyon.

Leila Chatti

Leila Chatti is a Tunisian-American poet and author of Deluge (Copper Canyon Press, 2020), and the chapbooks Ebb (Akashic Books, 2018) and Tunsiya/Amrikiya, the 2017 Editors’ Selection from Bull City Press. She is the recipient of a Barbara Deming Memorial Fund grant, scholarships from the Tin House Writers’ Workshop, The Frost Place, and the Key West Literary Seminar, and fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation of New Mexico, and Cleveland State University, where she is the inaugural Anisfield-Wolf Fellow in Writing & Publishing. Her poems appear in Ploughshares, Tin House, The American Poetry Review, and elsewhere.