On Moderata Fonte’s Feminist Reimagining of 16th-Century Venice

Female Friendships and Single Women in The Merits of Women

“Do you really believe,” Cornelia replied, “that everything historians tell us about men—or about women—is actually true? You ought to consider the fact that these histories have been written by men, who never tell the truth except by accident.”

— Moderata Fonte

![]()

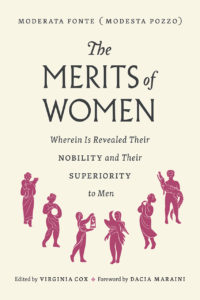

Virtually unknown before the 1980s, Moderata Fonte’s 1592 dialogue The Merits of Women has now taken its place among the great classics of early feminist thought, alongside works such as Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies, which precedes it by almost two centuries, and Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women, which follows it by the same length of time. Vividly imagined, challenging, witty, The Merits of Women is a significant work of literature, as well as a sometimes startlingly original discussion of women’s status. It is difficult to think of a work written before the 18th century that so powerfully evokes the realities of women’s daily lives and thinks so boldly about their “worth” and their due.

Moderata Fonte was born as Modesta Pozzo in Venice in 1555—in English terms, three years before Elizabeth I succeeded to the throne, and nine years before the birth of Shakespeare and Marlowe. Orphaned as an infant, Modesta was brought up first in a convent and then in her grandmother’s household, impressing all around by her brilliance as a child. The engaging biography of Fonte written by her onetime guardian Giovanni Niccolò Doglioni speaks of her as largely self-educated, reading her way through her step-grandfather’s library and pestering her brother to teach her Latin each evening when he returned from school. The family was a moneyed one: not from the governing patrician class of Venice, which gazes out at us scarlet-robed from the portraits of Veronese and Titian, but from the city’s other elite class, known as cittadini originari—literally, “original citizens”—who staffed the government’s administrative offices and the professions.

Fonte wrote from an early age, and, profiting from Doglioni’s contacts, she published her first work at the age of 26, in 1581: a romance of chivalry entitled Floridoro, telling the adventures of a young knight of that name. It is here that we first see her adopting her pseudonym, Moderata Fonte, which transforms her given name, meaning literally “Modest Well,” into the more euphonious and assertive “Moderate Fountain (or Spring).” The pseudonym celebrates Fonte’s creativity, playing on the traditional association of poetry with the Castalian Fountain on Parnassus, home to the Muses. At the same time, it leaves behind the bashful quality of “modesty,” so often associated with silence and self-effacement in women. Fonte’s pseudonym instead proclaims her “moderation”: a virtue suggestive of capacities for reason and self-discipline that not all of Fonte’s contemporaries acknowledged that women possessed.

In 1583, at the age of 27—late for the period—Fonte married a young government lawyer named Filippo Zorzi. By 1587, the couple already had three children. The demands of her young family slowed Fonte’s literary production, although she did continue to write. In addition to the works she published before her marriage (the Floridoro; a philosophical masque; and a verse narrative of Christ’s passion), we have two later surviving works by her: a sequel to her passion narrative, recounting Christ’s resurrection, and her masterpiece, The Merits of Women. From internal references, the composition of The Merits may be dated to the period 1588 to 1592. These were Fonte’s last years; according to Doglioni’s poignant account, she finished the dialogue the night before she died of childbirth at the age of 37 in 1592.

“Fonte’s boldest experiment in this speculative vein is to imagine an alternative Venice in which women might decide freely to opt out of marriage: the defining life experience in this period for women in this period, with the exception of nuns.”

We are accustomed to thinking of premodern women writers as beleaguered figures, who struggled to assert themselves within a society that conceived narrowly of women’s abilities and role. This is clearly true to some extent of Moderata Fonte. Doglioni tells us that she was was forced to dash off her literary works in the moments she could spare from her domestic duties, in deference to the “false notion” that “women should excel at nothing other than the running of their household.” The fact that Doglioni brands this notion “false,” however, alerts us to the fact that such prejudices were not universal in Fonte’s culture. Indeed, it seems to be the case that Venice was more conservative in its attitudes to women than nearby cities on the Venetian mainland, such as Verona and Vicenza, let alone nearby court cultures such as Mantua and Ferrara, where aristocratic ladies took a leading cultural role.

Fonte was well aware of this freer culture beyond the bounds of her city. She spent summers as a child on her grandfather’s estate near Sacile, in Friuli, north of Venice, and her correspondents included a young female writer of the Venetian mainland, Issicratea

Monti of Rovigo, so famed for her eloquence that she was selected while still an adolescent to deliver an oration to a visiting Hapsburg empress. Fonte also seems to have had contacts in Ferrara and to have known, at least by fame, the virtuoso singer Laura Peverara, one of the great female stars of that court.

As these examples suggest, women enjoyed a relatively high degree of cultural visibility in Italy in this period, by comparison with other countries in Europe. Already in the 15th century, we find a scattering of learned Italian women participating in the movement we now know as Renaissance humanism, based around the study and imitation of classical Greek and Roman culture. In the 16th century, as the vernacular rose to rival Latin as a literary language, and as literacy spread with the advance of print technology, women began to write in more significant numbers and to see their work published. The 1540s and 1550s saw a cluster of outstanding female poets active in Italy, including the Venice-based Gaspara Stampa, author of some of the most vivid and striking love lyrics of the Italian Renaissance, and the Roman Vittoria Colonna, a powerful innovator within the tradition of Italian religious verse.

Moderata Fonte was, therefore, not breaking new ground as a woman in aspiring to write and publish. This should not, however, lead us to underestimate the boldness and novelty of her work. Down to the mid 16th century, women’s writing had been largely limited to the genres of lyric poetry and letter-writing. When Fonte launched her literary career in her mid-twenties by publishing a lengthy chivalric romance, it was a highly unusual gesture, setting down a new marker for Italian women’s literary ambition. The same may be said of The Merits of Women. While it is not the first work in dialogue form to have been written by a woman, its scale, its complex architecture, and its broad thematic range mark it out as something quite new. Not since the days of Christine de Pizan, in the early 15th century, had a woman attempted writings of this scale and ambition; but, where de Pizan was an outlier, Fonte anticipated a strong trend in women’s writing in Italy. Between 1580 and 1620, Italian women published over 60 single-authored works, including epics, pastoral dramas, a tragedy, and prose and verse narratives of many kinds.

*

The natural world, as portrayed in the second book of The Merits of Women, is a purposive one, and essentially benign, despite mentions of earthquakes, famines, and poisons. God has created the great mechanism of the world as a habitat for humankind, his most beloved creation. Divine Providence has secreted healing powers into plants, spa waters, and precious stones to help us preserve our health, and it has filled the world with fruits and crops and animals for our nourishment and pleasure. One of the most lyrical passages in the second book hymns “friendship” (amicizia) as the governing principle of the universe, bonding the elements in harmony at a cosmic level, just as it bonds individuals and communities in peace and love.

It is against this background of natural harmony and cosmic “friendship” that the feminist speakers of The Merits of Women set the distinctly unfriendly social relationship between the sexes in the Venice of their day. Men and women are of the same species, the same flesh and blood, and they were created by God as companions for one another; yet men have so convinced themselves of their superiority to women that they have lost sight of this fundamental truth. Women are “otherized”; considered as lesser beings; deprived of the resources and education that might allow them to maintain themselves; forced into a position of humiliating dependence in which they must accept whatever harsh treatment their husbands or fathers choose to inflict. They are victims of “tyranny,” of illegitimate rule—an accusation of special potency in Venice, which prided itself as a rare beacon of republican liberty in a Europe mainly governed by monarchical regimes.

The notion that men’s rule over women constituted a tyranny was a challenging idea for the period, at a philosophical level, as well as that of social critique. The philosophical orthodoxy of the day, deriving from the ancient Greek thinker Aristotle, saw women’s subjection to men as a legitimate part of the natural order, not as an abuse or perversion. Indeed, Aristotle took the structure of the household as a paradigm for political organization, precisely on account of its supposed naturalness. Free adult males were dominant by right within the household, as the most rational and perfect exemplars of the human species. Women, children, and slaves were variously subordinate, precisely because their weaker rationality fitted them to obey, not to rule.

Fonte was not the first thinker to challenge this orthodoxy. On the contrary, a body of argument had grown up in the 15th and 16th centuries arguing against Aristotle’s hierarchical view of the sexes, and sustaining the alternative view that women were men’s equals by nature and that their subordination was a matter of custom. With the exception of Christine de Pizan, however, most writers who had argued for this position down to the late 16th century were men, often writing in a detached, theoretical manner, to the extent that some scholars have considered the Renaissance querelle des femmes (“debate on women”) as little more than an intellectual game or an opportunity for rhetorical display.

“Fonte’s women delight in one another’s company; they find pleasure in learning, intellectual engagement, creativity; they relish the freedom to speak unconstrainedly, and to define themselves for themselves.”

The Merits of Women is very different. Fonte does incorporate standard features of Renaissance “defenses of women,” such as a list of famous women of classical antiquity, and a learned discussion of physiology, and the humoral make-up of men’s and women’s bodies (cold and humid, according to medical tradition, in the case of women; hot and dry in the case of men). These more conventional and learned elements make up a relatively small part of her feminist speakers’ arguments, however; for the most part, they rely on experience and observation, describing the predicament of women in contemporary Venetian society in an unprecedentedly circumstantial and impassioned way. It is part of the power of the dialogue, as well as its charm, that it embeds its arguments within such a vividly realized social context. Fonte is concerned with proving women’s worth at a theoretical level, but she is far more concerned with what recognition of this worth on the part of society would mean concretely for women’s lives.

*

Fonte’s boldest experiment in this speculative vein is to imagine an alternative Venice in which women might decide freely to opt out of marriage: the defining life experience in this period for women in this period, with the exception of nuns. The best-educated woman in The Merits of Women, Corinna, speaks trenchantly of her decision to remain single, while her feminist companion-in-arms Leonora, a young widow, pronounces that she would rather drown than marry again. The setting of the dialogue is a garden designed by an aunt of Leonora’s who made the same life choice as Corinna, featuring as its centerpiece an allegorical fountain that serves as a manifesto for the joys of a freely chosen single life.

How much this choice of singledom was a reality for Venetian women at the time is an interesting question. Fonte intriguingly alludes to Corinna as a “young dimmessa,” suggesting that she is a member of a tertiary religious order for unmarried laywomen, the Dimesse, similar to the medieval Flemish beguines. It is possible that a few brave Venetian women did use the Dimessa identity to experiment with life outside marriage in this period, out of choice, rather than because they lacked the financial resources for a dowry. It is equally possible, however, that, in crafting her ideal of heroic singledom, Fonte is translating classical archetypes of female autonomy, such as the Amazons or Diana’s huntswomen-nymphs, into modern Venetian terms. Fonte is careful to set her dialogue in a place apart from the real world of Venice—or, better, in a liminal or threshold place, the temporary feminine utopia of Leonora’s aunt’s garden, suspended somewhere between the fantastic and the real.

Whatever its relationship to historical reality, one function of the advocacy of singledom within The Merits of Women is to make a powerful statement about women’s capacity for autonomy and yearning for freedom. Freedom is a leitmotif of the dialogue, along with amicizia, invoked by Fonte’s speakers at each turn. This is highly significant in context. Venice’s association with liberty is emphasized from the work’s opening lines, where we learn that the sea-borne city is “free as the sea itself,” and that her inhabitants enjoy “remarkable freedom.” As we see in the course of the dialogue, however, this legendary republican liberty is limited to men, the strutting lords of the city. By contrast, Venice’s women lead shackled lives, trapped in their gilded or less gilded cages.

Fonte’s exploration of what freedom might look like for women is perhaps the greatest philosophical novelty of The Merits of Women. It was axiomatic in Fonte’s society that elite women’s freedom of movement and interaction must be severely restricted, in order to preserve their sexual “honor” and hence the honor of their families. In this context, juxtaposing the notions of women and freedom could look suspiciously like a recipe for sexual license.

Fonte’s feminist speakers scorn the logic of this infantilizing treatment of women, which at its worst can lead them to being “shut up like animals within four walls.” Instead, they underline that women are rational beings, capable of regulating themselves morally without the need for external constraint. They also insist that, despite the innate kindness that makes women so crucial to the happiness of the human community, their purpose on earth is not limited to the role of caring for their husbands and children. Fonte’s women delight in one another’s company; they find pleasure in learning, intellectual engagement, creativity; they relish the freedom to speak unconstrainedly, and to define themselves for themselves. Archaic though aspects of the dialogue are (we no longer believe in the existence of the phoenix, or that the sun moves round the earth), in these respects Fonte’s speakers can seem startlingly modern. We may not always recognize our lives in their reality, but we recognize ourselves in their dreams.

__________________________________

From The Merits of Women. Used with permission of University of Chicago Press. Copyright © 2018 by Virginia Cox.