On “Mocha Dick,” the White Whale of the Pacific that Influenced Herman Melville

Tim Queeney Explores Ropemaking, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Jeremiah N. Reynolds’s Wild Tale

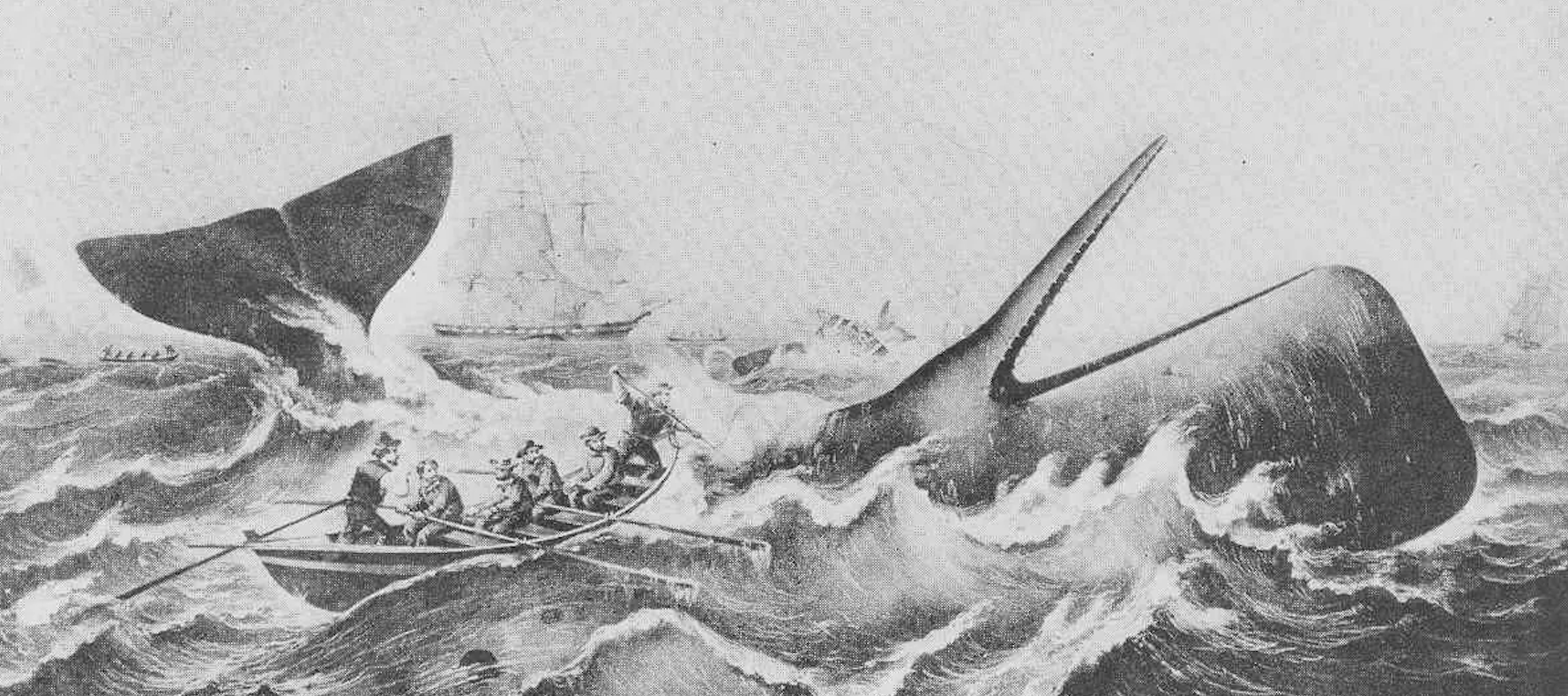

In 1839 Jeremiah N. Reynolds, an American newspaper editor, lecturer, explorer, and writer, published a curious tale of a famously fierce bull whale. The article, published in The Knickerbocker; or, New-York Monthly Magazine, claimed this cetacean had foiled the murderous attacks of many whalers over the years and was notable not only for his size and pugnacity but also for his coloration: “He was white as wool!”

Initially sighted off the coast of the Chilean island of Mocha in the Pacific, the powerful whale was dubbed Mocha Dick. (Dick was a generic name used at the time like Joe is today—Herman Melville follows this convention by naming his literary whale Moby Dick.) Reynolds claimed to have met the first mate of a whale ship who battled the great one with a darting harpoon and hundreds of feet of 3/4-inch line flying from the rope tub.

In his Knickerbocker piece, Reynolds retold the story of the fateful encounter:

At that instant, a whale “breached” at the distance of about a mile from us, on the starboard quarter. The glimpse I caught of the animal in his descent, convinced me that I once more beheld my old acquaintance, Mocha Dick. That falling mass was white as a snow-drift!…

“Here, harpooner, steer the boat, and let me dart” I exclaimed, as I leaped into the bows….I raised the harpoon above my head, took a rapid but no less certain aim, and sent it, hissing, deep into his thick white side!….

He now started to run. For a short time, the line rasped, smoking, through the chocks. A few turns round the loggerhead then secured it; and with oars a-peak, and bows tilted to the sea, we went leaping onward in the wake of the tethered monster….

By this time two hundred fathoms of line had been carried spinning through the chocks, with an impetus that gave back in steam the water cast upon it. Still the gigantic creature bored his way downward, with undiminished speed. Coil after coil went over, and was swallowed up. There remained but three flakes in the tub!

“Cut!” I shouted; “cut quick, or he’ll take us down!” But as I spoke, the hissing line flew with trebled velocity through the smoking wood, jerking the knife he was in the act of applying to the heated strands out of the hand of the boat-steerer. The boat rose on end, and her bows were buried in an instant; a hurried ejaculation, at once shriek and prayer, rose to the lips of the bravest when, unexpected mercy! the whizzing cord lost its tension, and our light bark, half filled with water, fell heavily back on her keel….

The dying animal was struggling in a whirlpool of bloody foam, and the ocean far around was tinted with crimson…the monster, under the convulsive influence of his final paroxysm, flung his huge tail into the air, and then, for the space of a minute, thrashed the waters on either side of him with quick and powerful blows….He then turned slowly and heavily on his side, and lay a dead mass upon the sea through which he had so long ranged a conqueror.

*

Reynolds’s colorful and gruesome account of Mocha Dick’s end was likely embellished for maximum effect on his readers. Melville was known to have read Reynold’s account and it clearly influenced him in writing his whaling novel.

Melville was known to have read Reynold’s account and it clearly influenced him in writing his whaling novel.

As embellished as it might be, however, the account does illustrate some key elements of the use of rope aboard whaling ships. What we today consider the sad business of hunting whales would have been impossible without many tubs of rope.

Indeed, this was rope use on an industrial scale. Each of a whaleship’s whaleboats carried upward of two thousand feet of rope in one or more tubs. And since each ship carried three to five whaleboats, the amount of rope needed just to conduct whaling operations on one whaleship was as much as ten thousand feet.

When extrapolated to the size of the American whaling fleet of seven hundred and thirty-five ships in 1846 and a worldwide fleet of 900, the result is a prodigious tangle of rope. And that doesn’t account for the rope needed for the whaleship’s standing or running rigging. Or further, the many more miles of cordage needed by non-whaling merchant ships and naval vessels.

With so much demand for working rope, the process of making cordage was transformed during the eighteenth century. When I talked to British rope historian, researcher, and knot expert Des Pawson, he stressed changes in this period.

“One of the landmarks must be when man started to use some kind of equipment instead of making rope entirely by hand,” Pawson said. “And at the end of the eighteenth century, huge steps were made in the manufacturing of rope with the development of the register plate and forming tube. There was a huge number of different patents developed…and rope manufacturing advanced by leaps and bounds.” Ropemaking transformed into an industrial enterprise.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the methods and materials of making rope became steadily more standardized. Whereas a variety of plant fibers like lime bast and flax were once used, in this period the process settled more fully on the use of hemp.

Given the right conditions, hemp plants can grow eight to fourteen feet tall, producing strong, long-length fibers. These fibers were separated from the plant by the process of retting. (Recall that lime-bast fibers were soaked in water to rett, or separate, them from the outer bark and the inner material—retting for hemp was a similar process.)

Bundles of fibers were then removed of seeds and other unwanted materials and organized into straight runs by hackling. The hackling process involved repeatedly drawing the fibers through a block of sharp metal spikes, looking like a giant’s hairbrush, called a hackle. To aid in this task, the fibers were often softened with small amounts of oil.

Once hackled, the fibers were turned into thin yarns by drawing them out with the aid of a spinning wheel. In this process the ropemaker would walk backward maintaining a steady pull on the yarn as the small hooks of the spinning wheel twisted the fibers together.

Multiple yarns were placed on a ropemaking machine equipped with hooks arranged in a circle. These hooks that held the yarns could all be spun together in the same direction with a hand crank. The multiple yarns were twisted together into thicker elements called strands.

The next step was to attach these strands to the rotating hooks of the ropemaking machine. The three strands were then twisted in the opposite direction that the yarns were twisted. This bringing together of the strands into rope was called “laying” the rope. Laying was aided by a big wooden conelike device called a “top.”

The top had three channels cut into it that guided the strands together. The ropemaking machine with the three rotating hooks, which spins the yarns into strands and the strands into rope, is fixed in place.

When the strands are combined into rope using the top, they are attached at one end to the rotating hooks and at the other end to a wheeled cart. As the rope forms, the twisting makes the completed rope shorter than the length of the original strands. Thus, the cart rolls slowly toward the rotating hooks as the rope takes shape.

So, the process was threefold: fiber bundles twisted into yarns, yarns twisted the opposite way into strands, and the strands twisted again the opposite way into rope.

An eighteenth-century British master mariner named Joseph Huddart noted in his sailing days that marine ropes often broke from the failure of the outer fibers, while the inner fibers had few, if any, breaks. Huddart realized that this was due to the uneven way the yarns were brought together when forming strands.

To remedy this disparity, Huddart invented a device called the register plate—a metal plate with a series of holes through which the yarns were guided. The pattern of the holes ensured that when forming the strands the forces were more evenly distributed.

An allied invention was the forming tube that compressed the yarns as the strand was made. These and other inventions made the process of ropemaking faster and resulted in better quality ropes that didn’t fail as easily.

Making a rope of any type required some space to spread out, space to lay out the lengths of material so they could be joined smoothly. In the early days of ropemaking the work was often done outside in an open area. As one history of ropemaking notes, “Originally a ropewalk was a level yard or field marked out with a series of pegged posts on which the yarn, strand or rope was hung as fast as it was spun, formed or laid.”

Because rope is a long linear object, a ropemaking area was a space much longer that it was wide. Eventually, ropemakers built roofs over these long ropemaking grounds to provide some cover from the rain. Over time walls and a floor were added and a long, narrow building called a rope-walk came into being. It was called a ropewalk because yarns were initially formed by walking the fibers backward.

The length of a finished rope was tied to the length of the ropewalk in which it was made. Remember that the completed rope ends up shorter than the original length of the strands. If we wanted a five-hundred-foot-long rope, for example, we needed a ropewalk of, say, seven hundred feet. Since the maritime world required long ropes for rigging ships and for deep anchor cables, that meant ropewalk buildings were usually many hundreds of feet long.

The Royal Navy had a requirement that its ships be equipped with sufficiently long rope cables for anchoring in two hundred and forty feet of water. And to anchor properly we need at least three times that length, or an anchor cable of seven hundred and twenty feet. So, to make a seven-hundred-and-twenty-foot cable we want a ropewalk one thousand feet in length.

The British government established three ropewalks along the Thames: at Woolwich, Deptford, and Chatham. The ropewalk at Chatham Dockyard in Kent, England, which still makes rope for sale, has been making rope for more than four hundred years and is one thousand, one hundred and thirty-five feet long.

In the United States, the ropewalk built at Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston in 1838 was a staggering one thousand, three hundred and twenty-five feet long and made naval ropes until it was closed in 1971. By 1810 there were a hundred and seventy-three ropewalks of various lengths in operation throughout the United States.

The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow captured some of the mesmerizing drone of a ropewalk’s relentless spinning machinery in the first two stanzas of his 1858 poem, “The Ropewalk”:

In that building, long and low,

With its windows all a-row,

Like the port-holes of a hulk,

Human spiders spin and spin,

Backward down their threads so thin

Dropping, each a hempen bulk.

At the end, an open door;

Squares of sunshine on the floor

Light the long and dusky lane;

And the whirring of a wheel,

Dull and drowsy, makes me feel

All its spokes are in my brain

Rope was part of a group of essential materials for shipbuilding, especially naval shipbuilding, that were called naval stores. Broadly defined, these were rope, tree trunks for use as masts, and liquid products taken from conifer trees like turpentine, rosin, pitch, and tar.

Rope was part of a group of essential materials for shipbuilding, especially naval shipbuilding, that were called naval stores.

The latter group of materials were all waterproof and could be used to help waterproof the ship. As we’ve explored previously, oakum picked from old ropes and then soaked in pitch or tar was used as caulking to fill the spaces between the planks of a ship’s hull.

Since the condition of the Royal Navy was of prime importance to the British Parliament, during the colonial era that body passed several acts that sought to entice or compel colonists in British North America to produce naval stores for the benefit of the mother country.

______________________________

From Rope: How a Bundle of Twisted Fibers Became the Backbone of Civilization by Tim Queeney. Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Tim Queeney

Tim Queeney is the author of Rope: How a Bundle of Twisted Fibers Became the Backbone of Civilization. He is the editor of Ocean Navigator, a magazine for offshore voyager. Tim's work has appeared in Professional Mariner, American History, and Aviation History. He has had short stories published in the crime anthology Landfall, Best New England Crime Stories 2018, and in the speculative anthology A Land Without Mirrors. Tim live in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, with his wife and a rescue dog, Frankie. A lifelong sailor, he teaches celestial navigation, radar navigation and coastal piloting ashore, where he tied plenty of knots and handled many a rope.