On Martha Cooper’s Exhilarating Photos of 1980s NYC Graffiti

“It’s a high you can’t find anywhere else.”

With a single snap of the shutter, Martha Cooper captured the searing rush of seeing a whole car make its debut on the line after being painted all night. You can all but hear the train thunder along the tracks and feel the ground rumble beneath your feet while a gust of wind hits your face. Is that the smell of spray paint? In a Martha Cooper photograph, seeing is more than believing—it’s a high you can’t find anywhere else.

It’s the kind of energy that just might change your life. Take it from Cooper, who knows better than anyone else. In 1980, she had been working as a staff photographer for the New York Post for three years, zipping around the city in a beat-up Honda Civic. She had been hearing about new trains being painted up in the Bronx—but she had to go to work.

“I said, ‘Fuck it, I just want to do this,’” she recalls. “I picked a very good time to quit the Post.” With her newfound freedom, Cooper became an integral figure on the burgeoning graffiti scene, her passion for her subjects matched by her boundless energy, which continues to this very day after more than 70 years of making photographs.

Standing inside her New York studio, Cooper grabs a copy of the 2018 book One Week with 1UP and flips to a picture in which she can be seen scampering up a hill on the run from the police. She laughs happily and says, “You understand the thrill when you do it and you’re afraid you might get caught. The illegal stuff is super exciting. Oh my goodness!”

“She made the conscious decision to celebrate that New York minute. She captured that better than anyone.”

You might just say Marty Cooper has not changed a bit. The thrill of adventure is in her blood. Just put a camera in her hands and she is ready to go.

“Marty is, and always has been, fearless,” says SKEME. “I was amazed at how adeptly she entered the yard, with no fear of heights or arrest, crossing the tracks with 6,000 volts surging through the third rail and climbing in between cars like a spry teenager.”

Martha Cooper, 1982. Image courtesy Martha Cooper. © Martha Cooper.

Martha Cooper, 1982. Image courtesy Martha Cooper. © Martha Cooper.

Though sporty and petite, with a pixie haircut, Cooper was a professional photographer in her 30s at the time, singularly focused on her goal. Now freelancing full-time, Cooper gave graffiti the National Geographic treatment: in-depth, longform, exquisitely detailed reportage—the best of which went into Subway Art, which she co-authored with Henry Chalfant in 1984.

STYLE WARS by NOC 167, 1981. © Martha Cooper.

STYLE WARS by NOC 167, 1981. © Martha Cooper.

Known as the “graffiti bible,” Subway Art spread the word around the globe from Cleveland to Copenhagen, inspiring a new generation of writers to live the life. Kids got their start tracing styles from the book and then trying their hand at a piece with cans of freshly stolen spray paint. They penned letters in homeroom before the bell went off, thanking Cooper for the inspiration and inviting her to Chicago (or Kent, or Soweto) to photograph their work.

Today, the letters arrive by email, detailing the possibility of paid work documenting graff everywhere from Tahiti to Thailand, India to Portugal, in recognition of Cooper’s influence and legacy. “Half the time I don’t even know where I am going. Just put me on the plane,” Cooper says with a laugh.

Cooper shares her love of adventure with the writers themselves, whether they are rappelling down the Manuel Gómez Morin Cultural Center in Mexico or sneaking into the #3 yard in Harlem during the dead of night. There, she documented a world few had ever seen, where Puma-shod writers moved like acrobats to paint masterpieces before the sun came up.

Love Stinks, 1982. © Martha Cooper.

Love Stinks, 1982. © Martha Cooper.

ART IS THE WORD by ALIVE 5, 1981. © Martha Cooper.

ART IS THE WORD by ALIVE 5, 1981. © Martha Cooper.

“Our shots were neither rehearsed nor coerced, neither directed nor suggested. Marty was there to capture the wild things in their natural habitat, and capture she did,” SKEME reveals. “Most amazing is that she found value in what we were doing, her documentation a testimony possessing such extraordinary evidentiary value in the case against us just being poor, truant, rowdy vandals. I’m glad she came along.”

Cey Adams agrees. “Martha was the first adult that really took notice of what we were doing,” says the graff pioneer and founding creative director of Def Jam. “She documented all the early work and she never asked for anything. She just showed up and took photographs. She traveled to different parts of the city. At the time I was too young to appreciate what it meant to have someone documenting your career at such a young age. She really cared. It was one of the earliest creative relationships I had, and I didn’t even know I was having it.

A natural collaborator, Cooper meets everyone where they are and quickly discerns the essence of the story in purely visual terms. “Marty does what great photographers do, which is to encompass all aspects of the scene in one image,” filmmaker Charlie Ahearn says. “Marty is not just snapping a picture; she is thinking about all the ways in which this is going to work. She has total freedom and is managing to be in the exact right place for the photograph.”

2BAD, Bronx, 1982. © Martha Cooper.

2BAD, Bronx, 1982. © Martha Cooper.

The perfect synthesis of music, style, fashion, art and attitude, Cooper’s photograph of Frosty Freeze, FAB 5 FREDDY, LADY PINK and Patti Astor standing in front of the Wild Style mural has become “the” image of Ahearn’s movie, even though it’s not a scene from the film. “It’s identified as this historical moment but it’s made up,” Ahearn says. “I wanted something that would carry to places like Brazil and Switzerland, and that’s what Marty’s photo did.”

Despite the immediate impact of her work, it would be years before Cooper would discover the legacy of Subway Art. She describes the book’s release as “a big disappointment. There was no hoopla. We didn’t do any publicity. I don’t remember having a release party. I don’t remember anyone talking about the book. It just seemed like it came and went.”

At the same time, the scene Cooper had been documenting was beginning to disappear. “The trains kind of died off right then. They had cracked down right at that moment,” she remembers. “When the trains stopped, there was a lull. With FUN and all those galleries, there was a feeling something was happening but somehow it flatlined.”

Suddenly, it seemed as though all that remained of graffiti’s golden age were the photographs in Subway Art, a paperback book whose covers fell off if you cracked the spine once too often. But that didn’t stop the book from becoming one of publishing’s greatest sleepers to hit the shelves, selling more than half a million copies over the next 25 years.

CAR WASH by CEY, 1982. © Martha Cooper.

CAR WASH by CEY, 1982. © Martha Cooper.

Unbeknownst to Cooper, Subway Art went underground and traveled the globe, finding its way into the hands of the next generation of writers coming of age. While some stole copies, others, like OS GEMEOS, made do with a black-and-white photocopied version of the book.

Although Cooper stopped shooting graff in 1984, she continues to stay in touch with writers she has met through the exchange of letters, postcards, holiday cards, artwork, photographs, handmade gifts, custom-made objects, toys, emails and ephemera that she keeps neatly organized in her studio.

Cooper opens boxes and flat files, drawers and closet doors, revealing an amazing wealth of historic objects she has received over the years, including DONDI’s whole-car sketch for “Children of the Grave, Part 2,” vintage black books, handwritten letters from CAINE 1, STAY HIGH 149, LADY PINK and BLADE, and a special 70th-birthday card featuring a picture of the “MARTY” mural painted at the Houston Bowery Wall in 2013.

You don’t just look at a Martha Cooper photograph, you feel it.

After searching, Cooper produces an envelope that contains a letter from SHY 147 dated May 12, 1983, along with a signed Polaroid taken in prison. “Martha thank you very much for the photos, they bring back memories of the good old times to me which are sometimes forgotten inside this prison,” he writes. “Martha, the world I share now is a whole different prison society and I need all the outside contact I can get so I won’t feel forgotten, and from what I see, you haven’t forgotten me like a lot of people have done.”

Not a chance. Cooper’s memory is as long as her archive. She ain’t forget . . . but for a long time it seemed as though the world had moved on. It wasn’t until Cooper began working on the book Hip Hop Files in 2004, when she reconnected with the artists in Subway Art, that she saw what had come of the seeds planted two decades earlier.

Cooper traveled across Europe, launching her new book to the next generation of graff writers, b-boys and b-girls. “We did 22 cities in 18 days or some crazy number, and people would come. They really showed up—and talked about what Subway Art meant to them. It was amazing,” she remembers.

Commissioned signs by graffiti writers including CRASH, NOC 167 & JEST, Bronx, 1981. © Martha Cooper.

Commissioned signs by graffiti writers including CRASH, NOC 167 & JEST, Bronx, 1981. © Martha Cooper.

After a 20-year detour, Cooper decided to jump back into the scene, her timing once again impeccable as her return to graffiti intersected with the rise of street art. With artists like Banksy spanning the divide between crime and commerce, everything was getting bigger—including the 25th-anniversary edition of Subway Art, which, now hardcover, measured nearly 12-by-17 inches.

Cooper sent a copy of the very first hardcover edition of the book across the pond to Bansky. “Wow, it’s a shame not all books can look like yours—they should have to be that size by law,” he wrote in a thank-you card Cooper keeps filed away. “Thanks for turning a lot of kids onto a whole different path.”

None of this was intentional and that’s why it works. It is pure, unadulterated love and mutual respect for the art of getting over, its practitioners, and the communities in which it lives. You don’t just look at a Martha Cooper photograph, you feel it. You want to be there, only you can’t, so you do it yourself.

Back in 2013, Dutch writer FURIOUS started remaking the pages of Subway Art on a lark. Like countless writers over the years, FURIOUS studied the hands of the masters, copying their techniques and adapting them in order to execute the perfect remix. Flicks were snapped and made the rounds on social media.

“Every now and then, it would reach the maker of the original piece. From their comments, I noticed how they appreciated that somebody on another continent was making an homage to the graffiti they made 40 years ago. That motivated me to keep on going,” FURIOUS says, as he works toward completing the re-creation of every single piece in the book.

As Subway Art celebrates its 35th anniversary, a new reverence for the work has also found its way into the hallowed halls of academia. Edward Birzin has been working on “Subway Art(efact),” his PhD dissertation at Freie Universität in Berlin. In his examination of the growth of graffiti from child’s play to an original art form, Birzin cites Subway Art as an integral text in the fixity and spread of graffiti to different lands and times.

“The universal appeal of graffiti might not be in the act of writing on walls and objects at all, but rather in its playful performance; walls and objects become a space on which young people can project their imaginations, dreams and aspirations,” Birzin writes.

“Cooper’s photographs told stories, showed the art moving and interacting with real and imagined dialogues, and captured the imagination of the graffiti writer. Her bird’s-eye views and context-filled images offered a view of graffiti which few had seen before. She gave insight into how graffiti writers imagined the ‘lives’ of their creations.”

Cooper’s photos not only captured the glory and grandeur of graff—they made everyone feel like a star, whether you were in the picture or not. “Marty is the first in my book to capture the moment and essence of the human condition like I have never seen before,” says legendary artist Lee Quiñones.

“She made the conscious decision to celebrate that New York minute. She captured that better than anyone as far as I am concerned. The heroic photograph that Martha has taken is one photograph—and that one photograph is to open the aperture of life to all of us and it can encompass anyone.”

__________________________________

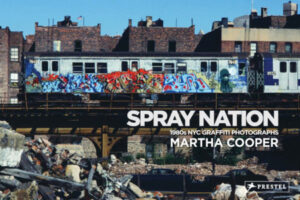

Excerpted from Spray Nation: 1980s NYC Graffiti Photographs by Martha Cooper, Edited by Roger Gastman © Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New York, 2022.

Miss Rosen

Miss Rosen is an art, photography, and culture writer based in Brooklyn.