On Lebanon’s Water Crisis and the Long Fallout of the Civil War

Charif Majdalani Traces a History of Corrupt Politicians, Deregulation, and Climate Catastrophe

Since biblical times, Lebanon has been seen as a beacon by the peoples of the Orient, by invaders from the East as well as those living in desert oases or in Palestine or Mesopotamia. It was the only known mountainous region, whose summits were said to bring men closer to the gods, or to the one God, and of course there was snow and water and infinite verdant valleys, with cataracts hurtling off cliffs, and gorges where cold torrents flowed. This natural paradise with its abundance of water and greenery led Lebanon to be compared to Switzerland in the Romantic period. For most of the twentieth century it was still seen as a dreamland by tourists from all over the world, especially by the global Lebanese diaspora, whose nostalgia for the sweetness of life in their homeland transfigured its mountains into places of legend.

Snow, torrents, water in profusion, and eternal greenery: for many years these features of the landscape were leitmotifs of the national narrative. For decades it was repeated that water was Lebanon’s oil, in other words its precious fortune—an inexhaustible fortune, what’s more, unlike the neighbors’ petroleum.

Except that now there is no more water, just as there is no more electricity. Of course this is not a new development, we’re old friends with taps running dry. But if this occurred even during the time—now seen as blessed—of the first republic, that was because the government of the day had taken no real initiatives to avoid water shortages at the end of the summer. During the thirty years of the second republic, on the other hand, there were countless projects. Numerous dams were built, destroying the mountains, the natural sites and landscapes, laying waste to valleys, gorges, and arable land. Many of the dam reservoirs dried up, because of leakages due to faulty construction or inaccurate land surveying. Opinions on their usefulness vary, but what is beyond a doubt is that nothing is known about the billions of dollars that were spent on them, involving fake invoices, cooked books, and gigantic amounts of siphoned-off funds.

According to all the hydrogeologists I’ve spoken to, there is not a single one of these projects that was costed lower than at least five times its real value, and all this for final results that were always below acceptable norms. This is how it goes in other areas as well: roads, bridges, public buildings. No documentation is ever demanded of the corrupt companies involved, which are always linked to politicians. As for the regulatory agencies, they receive spectacular bribes to close their eyes to the huge irregularities they find. Or if they wish to keep things legal, they are excluded from the public contract tendering process and reduced to bankruptcy.

For decades it was repeated that water was Lebanon’s oil, in other words its precious fortune—an inexhaustible fortune, what’s more, unlike the neighbors’ petroleum.

This morning I saw the first water truck making a residential delivery. It was parked in front of a building on Trabaud Street, in Achrafieh. The hoses were stretched up onto the roof of the building, the pump’s motor was whirring away, making an infernal racket. Nobody knows exactly where this private water sold without any legal authority comes from, or which aquifers are being pillaged with no scruples or oversight. But soon, with the summer coming on, this spectacle will be repeated in every street, for days on end—with, in the background of the picture, mountains rising up that were once the water reservoirs for the entire Middle East.

With the truck blocking Trabaud Street, I had to reverse out and take another route. Just before I started backing up, a passerby stopped in front of my open window and announced gravely that soon there would be no water at all, not just in this season every year, but all the time, because there would be no more fuel oil in the filtration and distribution plants.

*

The destruction of the landscape, the forests, and the mountains didn’t start with the construction of the dams. It started well before that, and is one of the irreversible consequences of the civil war. It is rare to see a conflict leading to an intense increase in building projects which, paradoxically, had more devastating effects than the destruction and ravages of the war itself. But that’s what happened here, where paradoxes abound. During the civil war, total deregulation, anarchy, and the absence of any oversight in applying the laws led to wild urbanization, stimulated by population shifts, speculation, and conspicuous consumption caused by the influx of money from arms and drug sales controlled by the militias and by the intense development of unregulated commercial practices.

Far from being brought to a halt by the return of peace, the deregulation that led to breakneck urbanization and irremediable ecological destruction continued during the ghastly second republic, when all excesses were legalized, as long as they earned money, always money, more and more money. I described all these mechanisms in my novel L’Empereur a pied, which very few readers interpreted as also being about the destruction of the environment and the devastation of a country through the physical violence inflicted upon it. For thirty years, the construction of monstrous buildings disfigured the towns and mountainsides. Individuals and groups who had been close to the militias, and who had become developers and unscrupulous billionaires in the orbit of power during peacetime, grabbed whole stretches of the coastline and beaches, then built them up and privatized them arbitrarily.

The same species of men gutted, smashed, and carved up whole mountains to extract the sand required for cement factories, and these quarries caused ghastly holes to appear in some of the country’s most beautiful landscapes. In 2008–2009, an advertisement financed by environmentalists portrayed Lebanon as a beautiful young woman receiving repeated blows, injuries, splinters, wounds, until she is completely disfigured and a horrifying sight. The commercial was so disturbing it was banned. Denial was still strong, and no one wanted to see what was going on. And yet the disfigured face of the country was always there before our eyes, and the work of destruction was increasing every day. Mind-boggling contracts continued to be signed, and monstrosities continued to be built against the law. Laws closing the quarries enacted by force were flouted and the despoiled public beaches were never restored because they belonged de facto to members of the caste that held the government hostage.

__________________________________

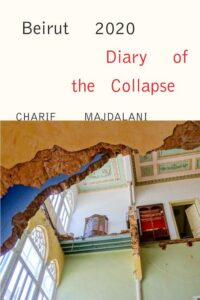

Excerpted from Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse by Charif Majdalani, translated by Ruth Diver. Published by Other Press.

Charif Majdalani

Charif Majdalani was born in Lebanon in 1960 and is one of the most important figures in Lebanese literature today. After living in France for thirteen years, he returned to Lebanon in 1993 and now teaches French literature at the Université Saint-Joseph in Beirut. His novel Moving the Palace won the 2008 François Mauriac Prize from the Académie Française as well as the Prix Tropiques.