On Leaving a Life and Moving to Alaska

(With a Pack of Sled Dogs as Companions)

There was a thing that happened to me every time I hit the road for a new adventure, and this time was no different. It was as if a spider’s silk had attached itself to me at one end, and the last familiar place on the other. I would start to drive away from that last place, and that little spinarette in my gut would tug more and more as I got farther away. “Go back!” urged this voice in my head. And then, somewhere along the way, the silk strand would break. Seamlessly, suddenly, I’d be singing out loud in the car. The tension would release and I’d float freely to the other end. My thoughts reaching forward instead of back.

Now they reached ahead to the Alaskan Interior and my little cabin and the dog-friends I would make. They ran along the Al-Can, to the heart of Denali National Park, up to the deep snow where I would surely flail and suffer a little bit. But nothing that wouldn’t add more character, that wouldn’t make me better. I felt my head full of possibilities, and my heart ready to accept them.

I was reading The Animal Dialogues by Craig Childs, and one night on the road when feeling especially lonely, I reached the chapter on coyotes. Their territory spans the United States from the East Coast to the West. A third of their population travels in packs, a third in pairs, and a third alone. While Childs is traversing a remote section of Arizona, he spots a lone coyote tramping the sands. The coyote barks, then listens. Barks again, then listens. Nothing answers him. He curls up and tucks his nose to his tail for a nap, becoming nothing more than a big rock in a desert landscape. He lays like that for an hour, stands, and becomes a coyote again. He throws his head back and uses his whole body to exert a howl out into the desert, tail in an arc between his legs. No answer. This doesn’t stop the coyote. He lets loose another howl, which is soon answered by a faint howl so far away, on the wind. That howl is answered by another shock of howls erupting from the west. Then the east. Then in all directions a cacophony of coyotes howling and yipping, filling a great emptiness.

Dad tolerated my daily crying episodes well, though his mind had been made up about Alfred from the day he first laid eyes on him. I remember my dad laughing in the kitchen as they shook hands, right after I picked him up from the airport. At the time I thought he was laughing at how nervous Alfred was. But I was beginning to realize it was at how undeserving Alfred was of his daughter. It had been less of a laugh and more of a scoff. How had this tattooed, jobless twentysomething won the heart of his teenage daughter, her whole future ahead of her, untarnished and full of promise? As we sat in a motel diner, it was evident that for Dad, this whole deal was good riddance to bad rubbish.

I missed my mother-in-law Karin’s loving lack of even one iota of judgment toward us, feeding bananas and eggs to the dogs, making the first steamed mussels and butter and wine sauce I had ever tasted; father-in-law Wally’s contagious, toothy laugh and his bolo ties and gorgeous Sioux jewelry, teaching me how to play cribbage on a finely carved piece of whalebone, making me believe the most ridiculous stories, stringing me along for minutes and then erupting into laughter. I knew I’d never see them again. Tears slid down my cheeks and onto my French toast. We returned to our room to find that Maximus had barfed on the floor and Moose decided he should probably pee there, too.

Maximus glowered at us from the corner of the room. “Rhat?” he said, lacking any sympathy for us at all at this point. “You guys are de asshose.”

“He did it, Mama,” Moose said.

We cleaned up the carpet, loaded the dogs back in the car, and hit the road.

Late one night we descended down the highway toward a large suspension bridge. Cars were stopped in a line ahead of us. In the headlights, a moose’s chest rose and fell. His crystallized breath ascended skyward in backlit steam as he lay on his side, taking up the entire lane with his massive body. The car that struck him shone on his final moments, the breaths deep and slow and peaceful, just outside Peace River.

I missed my mother-in-law’s lack of judgement… my father-in-law’s contagious laugh. I knew I’d never see them again.Dad and I pulled carefully around him, then crossed a bridge over the wide river and continued west and north to the Interior. The highway cut through one monochromatic winter scene after another, giving us glimpses of lonely places. Our drive was lit more by moonlight than sun, and the green glow over the snow burned brighter than any daylight we ever saw. The cold had veiled the stars, and they twinkled muted as though through wax paper. As though their breath had crystallized around them in radiating circles.

We listened to Guy Clark and Lyle Lovett, songs that made us think of Texas and summertime and childhood road trips. I had already driven this road once with Mom, on the way to my summer internship at the Denali National Park Sled Dog Kennels. In the three years since I had made that trek, I’d already forgotten the long, lonesome stretches of road and how you had to time your days to hit gas stations before they closed so you wouldn’t get stranded.

All the touristy places that were open in the summer were closed, and when we got to Liard Hot Springs at the corner of British Columbia and the Yukon Territory one early morning, we were the only ones there. We dug our bathing suits out of our bags and closed the back door of the car, the −20°F air freezing our nose hairs, causing them to stab the insides of our nostrils. We plodded down the long wooden boardwalk that snaked through a wetland cast in frost. Silvery crystals covered every board. In half a mile we arrived at the hot springs. Close in to the clear, hot water were large, protective trees. We eyed the changing room, noting the no alcoholic beverages sign. Dad looked at the bottle of Bailey’s in his hand and we both laughed and shrugged. In the adjacent changing area I screamed as my bare feet touched the frozen decking. We emerged and sunk ourselves into the steaming pool as quickly as we could, our hair freezing in mangled, white twists as we swam around, taking shots of Bailey’s. We could have stayed in the hot spring all day, but we forced ourselves to get out and change back into our frozen clothes. By the time we arrived back at the car our bathing suits were as stiff as cardboard.

That night, we arrived in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. We took pictures of the full yellow moon hanging serenely above a frozen landscape, reflecting in the near-still waters of the wide and sluggish Yukon River. Dad and I had two more days of driving before we would reach Healy, Alaska—a small mining town outside Denali National Park with about a thousand year-round residents. There, near the end of some frozen gravel road, was a one-room cabin I would soon call home. It had become dark. Solstice, the shortest day of the year, was a month and a half away. On that day, only four hours of daylight would shine upon the frozen Alaskan Interior. Our headlights formed two tunnels in a navy blue–black world. We turned right onto Stampede Road and passed streets whose names referenced little-known stars. Antares. Arcturus. Menkent. Until we came to Denebola. I learned later that Denebola meant “tail of the lion” and is the third-brightest star in the constellation Leo. We turned left and drove slowly down the narrow, snow-packed road. I could sense an openness beyond the car headlights— a huge expanse. An unknown. My heart pounded.

Then I saw it, the cabin whose photo I had memorized. It seemed to tower above the snow-ensconced tundra. It was built on tall pylons several feet above the ground, and a half-loft bedroom upstairs added more height to the small living space. We pulled into the driveway and shut off the car, staring. A soft light emanated from the multisize windows, glowing almost, landing on the snow in rectangular shapes. We opened the car doors and let Moose and Maximus out, and the four of us crunched through the snow to the back porch. We climbed up the steep steps, swept free of snow, and knocked on the heavy wooden door. A delicate antler was its handle. James, the newly divorced guy whose cabin I’d be occupying and whose dogs I’d be caring for, had mentioned he’d likely be next door at the neighbors’ eating dinner when we arrived. When the knock remained unanswered, we pulled the door open and stepped inside.

Maximus charged straight into the sixteen-by-twenty house, trotted purposefully across the green plywood floor, and pulled himself up onto a futon placed along the back windowed wall of the cabin. Maximus had never, ever sat on furniture before, but in pictures of the interior of the cabin, many dogs chose this futon as a dog bed. Max curled into a ball, head wedged against the futon’s armrest, nose pressed into his big, bushy tail, and fell asleep. He was not getting back into that car, no matter what, and he was making that very clear.

“You peopre are dead to me,” he said with a harrumph.

High above his head, white twinkle lights were strung in neat lines along wooden rafters. There was a small desk with built-in bookshelves overhead nestled in the corner. In front of the desk was a tall, rectangular window facing west. Lacquered, plywood countertops formed an L shape in the front corner of the cabin, with open shelving a few feet above them. On the shelves were exactly four stacked, blue plates. Exactly four stacked, blue bowls. Coffee mugs (four, all blue) hung from nails above the kitchen sink. A small tray held a handful of assorted cutlery. In the middle of the cabin was a large, square table with a blossoming Christmas cactus, pink petals falling on top of each other, cascading over the table’s edge. Adjacent to the big, square table, on the east side of the cabin was a cast-iron woodstove with a glass pane door and a rocking chair placed alongside it. A pile of cut birch wood was stacked neatly in a firewood holder beside a tall, windowed door that faced south. We opened the door onto another porch upon which sat an old, weathered couch covered in snow. Beyond that was a little trail that led into the darkness. The sled dogs must be out that way, I thought.

There was a knock at the door and in came James—a tall, ponytailed man maybe ten years older than me, wearing round coke bottle glasses and speaking in a soft voice.

“So you found the place,” he said, excited for our arrival and not a little relieved that someone would be here to care for his beloved crew of canines for the winter. He gave us a brief tour and, noting the absence of a refrigerator, lifted up a corner of the round rug under the rocking chair and revealed a square door with a silver D-ring latched onto it. He pulled on the D-ring and up came the trap door. James sat on the floor with his legs dangling down into a five-foot-deep cellar lined with white shelves.

“This is the cold hole,” he said.

He instructed us to put things we wanted refrigerated more toward the top and things we wanted to keep frozen more toward the bottom. The permanently frozen ground beneath the cabin (permafrost) plus the winter temperatures would keep everything cold no problem. “If the temperature drops to minus thirty or colder”—he nodded toward a milk crate next to the front door—“you’ll want to put things you don’t want frozen like milk or eggs or cheese in there.” At those temperatures, the cabin floor would keep those things refrigerated just fine on its own. Additionally, if I had a big grocery haul from town and couldn’t fit everything in the cold hole, the grill outside on the porch provided excellent frozen storage space, James said.

The permanently frozen ground beneath the cabin plus the winter temperatures would keep everything cold no problem.Dad and I walked back out to the car for our things and James bid us good night as he made his way back over to the neighbors’ where he would stay for a few days, coming over during the day to make sure I learned “the systems.” The moon was so bright on the snow that he didn’t need a headlamp, and we watched his dark silhouette stride up a small hill, mountains faintly outlined in glowing moonlight green at the edge of all that blackness.

Dad and I returned to the cabin, cracked open two ice-cold Alaskan Winter Ales that had become near-frozen in the car, and slouched onto the futon and the rocking chair. The labels on the beer bottles looked exactly like the scene outside: navy blue sky pinpricked by stars, a full moon glowing onto snow-covered spruce trees. The taste of the beer made us both let out that “cold beer” sigh of contentment like people do in commercials. We laughed and looked up at the twinkle lights in the rafters. Dad petted the giant, heavy head of Moose, who had surreptitiously crawled onto the futon between Dad and Maximus, pretending he didn’t weigh ninety-eight pounds and wasn’t really the size of a small horse. Dad nodded as he looked around the house and his gaze eventually rested on my permanently smiling face. Without saying a word, he seemed to concede the rightness of it all. He seemed to know I had wound up just where I belonged.

__________________________________

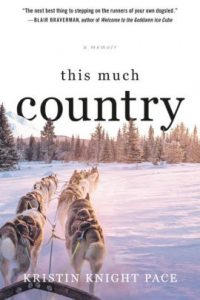

Excerpted from This Much Country by Kristin Knight Pace. Copyright © 2019 by Kristin Knight Pace. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Grand Central Publishing.