On Land, Community, and Celebration in the Historic All-Black Towns of Oklahoma

Tina M. Campt Looks at “Black Possibility Made Real”

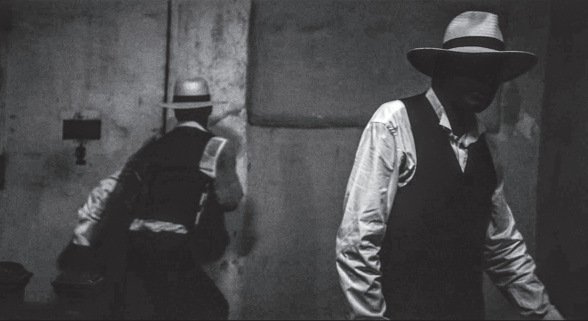

Complex gradations of gray guide us through a haunting landscape of shadows and open spaces. Solitary walks, absent expressions, and distant looks render a pensive portrait of Black interiority. A clap of thunder and a bolt of lightning jolt us to attention. They signal the coming of bad weather on the horizon. Yet, as the weather shifts and the storm descends, no one seems to flinch or stir. On the contrary, the foreboding clouds and the drama of the weather energize this landscape, infusing anticipation and intensity into the quiet scenes of Black community it depicts.

Kahlil Joseph’s 2013 film Wildcat, with its evocative score by electronic music producer Flying Lotus, renders a rural Midwestern town as a black-and-white rumination with sumptuous texture. The film captures confident, contemplative blackness set in a landscape that, to some, might signal precisely the opposite. It renders rural spaces that Black folks are schooled to avoid. They are spaces of foreboding that silently telegraph a history of white sheets and knotted rope, flight and frequent recapture. But Joseph’s images refuse this narration of their landscape, repainting it instead in a markedly different tonality.

*

Cowboy hats crown Black and brown heads. They mount and master steers and stallions, and parade linearly or laterally in majestic formations. The rodeo is their ritual celebration. It is a celebration of a community structured by a relationship to land and livestock in a town formed as a means of protection. It is a community created with the intent to transform a landscape of oppression into a domicile of possibility.

Wildcat, dir. Kahlil Joseph (2013).

Wildcat, dir. Kahlil Joseph (2013).

Between 1865 and 1915, at least 60 so-called All-Black Towns were settled in the United States, over 20 of which were located in Oklahoma. Freedmen from the south initially founded the All-Black Towns of Oklahoma on land provided by members of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes, comprising Native American tribes of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole. At the end of the Civil War, former slaves of the Five Tribes settled together for mutual protection and economic security. Grayson, Oklahoma, formerly known as Wildcat, is one of thirteen such towns that survives to this day. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society:

When the United States government forced American Indians to accept individual land allotments, most Indian “freedmen” chose land next to other African Americans. They created cohesive, prosperous farming communities that could support businesses, schools, and churches, eventually forming towns. . . . Many African Americans migrated to Oklahoma, considering it a kind of “promise [sic] land.”

When the Land Run of 1889 opened yet more “free” land to non-Indian settlement, African Americans from the Old South rushed to newly created Oklahoma. . . .

In those towns African Americans lived free from the prejudices and brutality found in other racially mixed communities of the Midwest and the South.

Black cowboys shuttle massive beasts through fenced mazes into tight corrals. They mount horses primed to accelerate. They circle and give chase. They ride horizontally and dismount dramatically. They tackle beasts and wrestle them to the ground; grab and tussle with horns and rope. They are pulled and pressed downward, and yet they rise and rise. They bounce improbably upward, dusting themselves off gracefully, to ride and tackle over and again. An accelerating Black cowboy leans into a tight corner turn. But the turn is too tight. Careening downward, the horse buckles and yields to gravity. But gravity does not capture its rider. Falling under the horse’s full weight, a Black cowboy never dislodges. Cowboy and horse remount together to full stature, shrugging off both the concern and approval of another cowboy, who rushes to extend a hand of compassion and care.

Wildcat, dir. Kahlil Joseph (2013).

Wildcat, dir. Kahlil Joseph (2013).

Black community, Black celebration. Wildcat captures the pleasures and intimacies of the Black quotidian in a community created as an antidote to white supremacy. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white Oklahomans sought to block African Americans from settling in All-Black Towns like Grayson. White farmers pledged never to rent, lease, or sell land to Black residents, while others refused to hire Black laborers. Mid-century droughts and the Great Depression dealt an unrecoverable blow to some All-Black Towns. Yet, while so many of them failed, Grayson lives on.

Wildcat, dir. Kahlil Joseph (2013).

Wildcat, dir. Kahlil Joseph (2013).

Wildcat visualizes an impossible narrative of Black possibility made real. It is an impossible narrative of Black futurity told through a Black gaze. It is a future willed into being through the physical and affective labor of first people, freedmen, and former captives. It is a labor of love and community, of pleasure and pain, of affirmation and refusal.

__________________________________

Excerpted from A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See by Tina M. Campt. Reprinted with Permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2021.

Tina M. Campt

Tina M. Campt, a Black feminist theorist of visual culture and contemporary art, is Owen F. Walker Professor of Humanities and Modern Culture and Media at Brown University and a Research Associate at the VIAD (Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre) at the University of Johannesburg. She is the author of Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe, Listening to Images, and other books.