On James Baldwin's Dispatches from the Heart of the Civil Rights Movement

The Making of an Iconic Essayist

In part one of “Beyond Simplicity,” (which originally appeared in Brick 101), Ed Pavlić explored the complex motivations that brought James Baldwin back from France to the US and sent him on a tour of the Deep His South to witness the nascent—but also ages-old—Freedom Movement. At age 33, Baldwin had never been to the American South. His reasons for going were deeply personal and fiercely political, a combination he lacked a vocabulary to describe. Part two, below, traces Baldwin’s historic journey through essays published soon after he returned from the trip, accounts from memory later on, and letters he wrote to friends and family while he was there.

![]()

V.

“Nothing, sir”

Baldwin in Charlotte, North Carolina

James Baldwin began his trip to the South by flying from New York to Washington, D.C., on September 9, 1957. On assignment for Partisan Review, Baldwin made stops over the next six weeks in Charlotte, Atlanta, Montgomery, Tuskegee, Birmingham, Nashville, Little Rock, and Arlington, Virginia. As he told his brother, the plan was to be back by October 22. Flying between the major stops, Baldwin moved through a territory at once startlingly strange and terrifyingly familiar. He returned to New York, he reports in No Name in the Street, lugging a suitcase stuffed full of “contraband” and “underground secrets.” He collapsed in the apartment of an acquaintance named Furneau in the East Village. As Baldwin recalls, “for five days,” while worried friends and family searched the city for him, he couldn’t move:

While in the South I had suppressed my terror well enough, in any case, to function; but when the pressure came off, a kind of wonder of terror overcame me, making me as useless as a snapped rubber band.

Baldwin pulled himself together and went back to the MacDowell Colony to work on his next novel and a version of Giovanni’s Room to be performed at Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio in New York that spring. Struggling with chronic medical symptoms resulting from stress and strain, he would also work through 70-odd pages of handwritten notes from his Southern tour, which he’d turn into two short essays: “The Hard Kind of Courage,” rejected by Look magazine and published by Harper’s in October 1958; and “A Letter from the South: Nobody Knows My Name,” which Partisan Review published a few months after that. Both would be part of Baldwin’s second book of essays, Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son, in 1961.

The postmark is smudged, but early in October 1957 Baldwin sent a letter to Mary Painter from Harry Golden’s office at the Carolina Israelite. The trip had only begun; Charlotte was the first stop. He wouldn’t be speaking with Dorothy Counts, whose photograph—as discussed in part one of this essay—Baldwin would mistakenly recall as the initial motivation for the trip. Counts father, a prominent minister, had already removed her from the once-again-all-white Harding High School. But, Baldwin told Painter, he’d been up until midnight talking with Gus Roberts and his mother. Gus and his younger sister Girvaud accounted for half of the Black students sent to white schools in Charlotte that fall. From the group admitted in 1957, Gus would be the only student to graduate from a previously all-white high school.

Baldwin wrote to Painter that he could feel a weight rapidly filling his head and heart during that evening with Mrs. Roberts and her children. (Their father was at work.) Baldwin was there as a reporter, but he was far from detached. He clearly wanted to help, to join the fight. But how? Saying he trusted neither his publisher (Beacon Press) nor his agent (Helen Strauss) to do it, and likely as much for himself as for the embattled young man, Baldwin asked Painter if she’d buy a copy of his first book of essays, Notes of a Native Son, and mail it to Gus Roberts at his home in Charlotte.

Reprinted as “A Fly in Buttermilk” in Nobody Knows My Name, Baldwin’s first piece from his tour was published as “The Hard Kind of Courage” in Harper’s. Baldwin focused on Gus Roberts’s first days at Central High School. Sitting in the quiet of the family’s living room while Gus sat on the sofa exhibiting a “nearly fanatical concentration on his school work,” Baldwin encountered for the first time what it meant to cease playing it safe. In his letter, he told Painter he didn’t have words to describe the scene; to the readers of Harper’s, he reported a situation doused in an almost mineral quiet. For Baldwin, who not long ago had been living in Corsica and in Paris, trapped in “the prison of [his] egocentricity,” struggling with an amorphous pain and spending nights on “the underside of Paris, drinking, screwing, fighting,” the scene with the Roberts family was unspeakably ordinary. Gus himself, Baldwin wrote, “seemed extraordinary at first mainly by his silence.” “‘Good evening, sir,’” Gus had said when Baldwin entered the room, “and then left all the rest to his mother.”

Designed to appear ordinary, Black Southerners’ complex use of silence was, in fact, partly to blame for the heavy panic Baldwin felt filling his insides. The Roberts family maintained a steely silence and protective distance between themselves and their dangerous predicament. Most certainly, no one in their household was playing it safe. So, was the distance created by their silence an illusion or a form of real power? Sensing a strength he couldn’t neatly account for, Baldwin described Mrs. Roberts as “quiet looking.” When he asked her about Gus’s first day at Central: “Nothing, she told me, beyond name calling,” had marked that day. On the second day, the “students formed a wall between G. and the entrances. . . keeping him outside.” Turning to Gus, Baldwin asked, “‘What did you feel when they blocked your way?’” He described the young man’s reaction: “G. looked up at me, very briefly, with no expression on his face, and told me ‘Nothing, sir.’” Baldwin guessed that “pride and silence were his weapons.”

Baldwin asked if Mrs. Roberts had had any ugly encounters with white folks over Gus’s attending Central. (Strangely, not a word appears about Girvaud Roberts’s experience integrating Piedmont Junior High that fall.) Mrs. Roberts reported nothing. Baldwin added: “Nor, she told me, had anyone said anything to her husband, who, however, by her own proud suggestion, is extremely closedmouthed.” As the evening wore on, Baldwin “began to realize” that, as concerned Gus’s experiences at Central High School, “there were not only a great many things G. would not tell me, there was much that he would never tell his mother.” Baldwin asked how other Black families felt about their decision to have Gus “reassigned.” Mrs. Roberts said that “a lot of them don’t like it,” but Baldwin gathered “they did not say so to her.”

The Robertses weren’t the only ones keeping a buffer of quiet between themselves and what it meant, or might mean, to cease playing it safe in North Carolina. The next day, Baldwin encountered another kind of silence. He interviewed Ed Sanders, unnamed in the essay, the principal of Gus Roberts’ new high school. When the students had blocked Gus’s entrance, it had been Sanders who parted the crowd, “took him by the hand,” and walked with him inside “while the children shouted behind them, ‘Nigger-lover.’” Baldwin wrote: “I asked him to describe to me the incident. He told me that it was nothing at all: ‘I’ve seen them do the same thing to other kids when they were kidding.’” Baldwin sensed that Sanders would like to dismiss the situation as normal adolescent mischief “despite the shouts (which he does not mention) of ‘nigger-lover!’”

In the published essay, Baldwin mostly stays out of the way while recording how people navigated segregation and the efforts against it via a tactical distance from their own senses. Sanders’s comments—quite possibly his memory—edit out students’ racist chants. When Baldwin asks about his personal view, Sanders avows his non-racist way of seeing: “I’ve never seen a colored person toward whom I had any hatred or ill-will.” What he does see, however, presents a different picture, one that’s harder to accept. As a school administrator, Sanders tells Baldwin: “it seems to me that colored schools are just as good as white schools.” In his interview with Principal Sanders, Baldwin encounters, again, evidence of perceptions avoided, feelings pre-empted, and speech silenced.

As for Sanders and other white Southerners, Baldwin thought they would have to arrive at a radically different apprehension of Black people and the world around them all.

The fast-accumulating weight Baldwin confided to Painter about likely had much to do with his position as an outsider, one alert to an electricity everyone but him had insulated themselves against. For Gus Roberts and his family, silence served a tactical role that allowed them to attack the system of segregation while avoiding aggressive postures.

Baldwin knew that silence gave way to sound somewhere; he’d laced his own work and life with the music that was one way Black people gave voice to experience without “speaking” about it. As early as 1951, in “Many Thousands Gone,” he’d written that Black music told a story, “which no American is prepared to hear.” As for Sanders and other white Southerners, Baldwin thought they would have to arrive at a radically different apprehension of Black people and the world around them all. He knew this would lead to a difficult reappraisal of themselves as well: “As the walls come down they will be forced to take another, harder look at the shiftless and the menial and will be forced into a wonder concerning them which cannot fail to be agonizing.” When Baldwin very gently pushed Principal Sanders (whom he described as “bewildered and in trouble”) beyond the passive racism and paternalism of his avoidances, Baldwin said the man’s “eyes came to life,” and he found himself “staring at a man in anguish.”

The situation with the Roberts family was similar but also very different. Both Gus and his mother had steeled themselves to navigate verbal abuse and psychological torture. They weren’t, however, converts to philosophies of non-violence. Gus and his mother were ready to fight, which at the time pretty much meant they were ready to die. As Baldwin’s time with the Roberts family ended, Mrs. Roberts spoke about her fears and hopes for the future. She also noted a limit to her avoidance of aggressive postures and an insistence upon self-defense:

“I don’t feel like nothing’s going to happen,” she said, soberly. “I hope not. But I know if anybody tries to harm me or any one of my children, I’m going to strike back with all my strength. I’m going to strike them in God’s name.”

Like his mother—possibly rehearsing private conversations—Gus snaps momentarily out of his weaponized silence when the question of self-defense arrives. Baldwin wrote:

“It’s hard enough,” the boy said later, still in control but with flashing eyes, “to keep quiet and keep walking when they call you nigger. But if anyone ever spits on me, I know I’ll have to fight.”

VI.

“war between Southern cities and states”

Atlanta

Continuing his journey, Baldwin flew from Charlotte to Atlanta. He didn’t stay long. Focused on his findings there, “A Letter from the South: Nobody Knows My Name” presented a summary of his trip to readers of Partisan Review’s winter 1959 issue.

Now, almost all readers encounter Baldwin’s work in his books or in collected volumes, so we forget that most of these essays were written as assignments for fees from magazines with different audiences and editorial approaches. Baldwin’s early essays about the South were published by magazines as different as Harper’s, Partisan Review, and Mademoiselle. The negotiations weren’t ever easy; here and there they proved impossible. During the late spring of 1957, Baldwin, still in Corsica, lamented having to give up a $1,000 fee from Holiday magazine because he couldn’t bring himself to write the essay about the island they wanted, and he knew very well they couldn’t possibly publish the essay about the island he wanted. One thousand dollars for an essay was serious money. Baldwin’s advance for Giovanni’s Room had been $400. His rate for Partisan Review was a cent and a half per word.

Baldwin had ushered readers of his Harper’s piece “The Hard Kind of Courage” into a close proximity to racially distinct registers of Southern silence. In contrast, his Partisan Review piece presents an impersonal account of social and political structure. In Harper’s, Baldwin deployed his novelist’s skill at capturing intimate atmosphere and the quiet intricacies of personal experience. For Partisan Review, he presented himself as a capable surveyor of history in the making.

“No integration, pending or actual,” was happening in Atlanta when Baldwin stopped there on his way to Alabama, where the victory in the Montgomery bus boycott had emboldened movements and sparked violent reprisals in Tuskegee and Birmingham. According to Baldwin’s sources, Atlanta’s approach to progress was led by a relatively strong Black middle class acutely aware of “their position as a class—if they are a class—and their role in a very complex and shaky social structure.” For instance, he thought there was no protest movement or boycott to end segregation on the buses because the city’s “well-to-do Negroes never take buses, for they all have cars.”

The Black middle class and the white mayor found themselves in tense cooperation surrounded by state politics that, to put it mildly, favored neither of their interests. This situation brought about an alliance based upon the fact that “Atlanta is really growing and thriving, and because it wants to make even more money, it would like to prevent incidents that disturb the peace, discourage investments, and permit test cases.” Black middle-class participation in the so-called peace and prosperity of Atlanta’s progress was an unstable arrangement. On the one hand, its members meant to push—peacefully, but push—the mayor for racial progress. On the other, all of Atlanta “belongs to the state of Georgia,” which was committed to the racist status quo. Baldwin noted an example:

When six Negro ministers attempted to create a test case by ignoring the segregation ordinance on the buses, the governor was ready to declare martial law and hold the ministers incommunicado.

In the pages of Partisan Review, Baldwin contends that this “war between the Southern cities and states is of the utmost importance, not only for the South, but for the nation.” Bringing the intimate and social together at the close of the essay, he warns how “this failure to look reality in the face diminishes a nation as it diminishes a person.” He describes the US as engaged in exactly the same kind of avoidance Principal Sanders employed in Charlotte: “the South imagines that it ‘knows’ the Negro, the North imagines that it has set him free. Both camps are deluded.” Baldwin closes with a version of freedom that’s worth the effort: “Human freedom is a complex, difficult—and private—thing. If we can liken life, for a moment, to a furnace, then freedom is the fire which burns away illusion.” If that’s so, letters he sent to friends and family over the next week describe a fiery passage indeed. Baldwin’s illusions of a private life protected from social and political forces dissolved under the pressures of existence in the South. His encounters with Black people’s efforts to change the South presented him with politicized versions of personal life, with methods for ceasing to play it safe. In ways that would take more than a decade for him to fully understand, he learned how to change—which by 1957 meant save—his life.

VII.

“the fire that burns away illusion.”

Baldwin’s Letters from Alabama

In “A Letter from the South: Nobody Knows My Name,” Baldwin remembered being told while he was in Charlotte that “Charlotte is not the South. . . You haven’t seen the South yet.”

“Charlotte seemed quite Southern enough for me,” he wrote, “but, in fact, the people in Charlotte were right.” By the end of the second week of October, Baldwin had flown from Atlanta to Montgomery, Alabama. He’d spend at least a week traveling between Montgomery and Tuskegee before flying to Birmingham later that week. If Charlotte had been “quite Southern enough,” Alabama proved to be way too much. What he found there, however, would be transformative upon reflection. His essays about the South from the 1950s and early 1960s barely mention Alabama, Birmingham not at all. By the time he wrote No Name in the Street, the recollections had blurred and blended with pain and time and travel and victories, and with the torture and murder of so many people. But the essays Baldwin wrote contemporaneous with his early travels to the South are replete with silences.

Baldwin sent a letter from Tuskegee to his brother David in New York City in the evening mail on October 11, 1957. His mounting fear seeps through his persona of the older brother. He says he can’t sleep and he’s already feeling apprehensive about writing to the public about the trip. After detailing the itinerary, he laments the accumulated effects of what he’s encountered: he felt the country was turning its back on itself, refusing to answer the call to become itself. Forced to cooperate in the face of white resistance to desegregation, which followed directly from the Supreme Court decisions in 1954 and 1955, Black people, Baldwin thought, were fairly united. He could see the toll this battle was taking, and would take. Those Black people who could be would be broken, he wrote, kept from working, kept from eating, attacked, maimed, driven insane, and shot. Still, the outcome was absolutely certain. Baldwin saw the South, the US, and even the world as being in the midst of immense and irreversible change. White people, given their present condition, would hardly be able to stop what had been set in motion, of that he was certain.

In Atlanta, Baldwin had met Martin Luther King Jr., who still lived and preached in Montgomery. King had been staying in a motel, working on a book. Baldwin, who was not predisposed to adore clergy, found King remarkable from the start. Clearly Baldwin’s favorable impression owed to his mounting fear since being in Alabama and to his awe at King’s leadership in the recent victory over segregation on Montgomery’s buses. Baldwin explained to David that he’d ridden a desegregated bus in Montgomery and had felt the stifled rage of the bus driver as well as the calm power of Black bus riders who were sitting in victory all over the bus. Recalling that ride three years later in “The Dangerous Road before Martin Luther King,” he’d remember that white people “sat there, ignoring them, in a huffy, offended silence.” “I think that I have never been,” he would continue, “in a town so aimlessly hostile, so baffled and demoralized.” In Montgomery, Baldwin had also met Reverend Ralph Abernathy, King’s chief strategist, who stressed that the goal was to abolish segregation in all forms throughout the capital and then across the state. Baldwin told his brother the movement, led by King, had been holding packed public meetings in Montgomery for more than two years. White people, meanwhile, were shocked and terrified because Black folks they thought they knew had all transformed, as if overnight, into a force determined to change the social order.

In Atlanta, Baldwin had met Martin Luther King Jr., who still lived and preached in Montgomery. King had been staying in a motel, working on a book. Baldwin, who was not predisposed to adore clergy, found King remarkable from the start.

Baldwin himself was amazed at the mobilized behavior and disciplined demeanor of the Black people he met in Alabama. He’d sat with Gus Roberts and his mother and attempted to gauge their determined and silent insistence. Now, he felt that resolve in organized and principled revolt. The Southern power—Black power—Baldwin had encountered in Charlotte was being mobilized; this was no illusion. As Baldwin would often remark in later years, “Black people in this country come out of a history which was never written down.”

Its power had been transmitted via complexly open secrets, in codes, often enough in music. To David, he marveled that King had advised those in the movement against violence and against hatred. This wasn’t that unusual; the surprise was that the people seemed to follow his lead. In this, Baldwin felt American illusions about Black people’s contentment and powerlessness coming apart. It certainly was difficult and dangerous to be Black in Montgomery, Baldwin told his younger brother, but being white would be worse. It had to be utterly terrifying, he wrote. Black folks had played a hand white people hadn’t seen coming, hadn’t known existed. There was a power in the South that couldn’t be contained. White people, Baldwin wrote, were reacting in disastrous ways and would likely continue to do so. They were trapped in an invisible cage. Meanwhile, he told his brother, King and Abernathy preached Christian love. Baldwin underscored that this was no catch phrase; these Christians were serious about the fundamental basis of love in their message, in their tactics, and in their lives.

The sum of white reaction wouldn’t defeat Black people’s power. Baldwin thought that its most serious ill-effect would take place in the lives of white families, in the homes and churches of white people who resisted the change that would soon surround their lives. More than surrounded, all of Southern life had long been suffused with that power, Black power. That power had cooked the food, it had cared for the children and the elderly. Everyone’s children and elderly. And it had built a distinct way of life; a people had been formed who most white folks had, in fact, never looked at. Now, Black people had stood up and revealed their power in a new dimension. Beholding this, Baldwin thought the white folks of Alabama were like Ezekiel in the valley of death. A miracle had saved Ezekiel. Baldwin thought, maybe hoped, another one would save white people from themselves.

Signing off his letter to David, Baldwin reasoned that the Black power now in evidence in Alabama was very real, but, after all, Montgomery was really just a town. Things would be different in cities. He told his brother he’d written the letter to relieve uneasy feelings about the journey that awaited him. He asked him to pray that God would help him do what he needed to do, to write what he’d have to write. He signed off, as he usually did in letters to his brother, as Jamie.

Less emotionally guarded with Mary Painter than he was with his brother, Baldwin wrote her from Tuskegee before leaving to hear Martin Luther King Jr. preach at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery. He stressed that the trip was taking its toll and that in Montgomery, for the first time, he’d been truly afraid. He detailed for Painter the power dynamics shaping up in Alabama and said the movement to desegregate stores in Tuskegee resembled the bus boycott in Montgomery. Surely store owners in Tuskegee could benefit from what the Montgomery bus company learned after nearly going out of business. However, according to the Tuskegee newspaper, local officials believed that Black folks in the country would still shop at segregated stores even if the Black middle class in town might observe the boycott. Misguided by a mixture of false class assumptions and racism, white officials had been very wrong about that. Baldwin reported that on the Friday afternoon he’d been there, the downtown area was empty and many of the stores were closed.

For most of his letter to Painter, Baldwin reflects on how emerging Black power had put white communities under pressure in ways that, it seemed to him, exposed a tragic lack of white leadership. In No Name in the Street, imagining himself looking at the photo of Dorothy Counts in Charlotte, Baldwin remembers thinking, “Some one of us should have been there with her!” In fact, as he explained to Painter, Harry Golden had said that Counts would have most likely still been at Harding High School if a few respected Charlotte business owners had come to the school on the second day and escorted her into the building. Golden’s idea clearly impressed Baldwin, who would suggest this move to white leadership, including President Kennedy and his brother. It’s too easy to imagine, he told Painter, that huge groups of people are evil and nasty. What Baldwin saw was that white people in the South lacked leaders. If someone stepped up to lead, he thought, people would follow them.

More than malevolence, he told his friend, it was disorientation that afflicted white people in the Deep South. The so-called leaders (people such as Senator Russell in Georgia and Governor Hodges in North Carolina) shamefully hid behind what passed for public opinion. Baldwin wondered to what extent the public really had any opinion. Maybe, he reasoned, the public had reflexes that could be directed and fears that could be assuaged. He thought it was the role of leaders to create public opinion in the true interests of the people, people such as the owners of the empty stores of Tuskegee, for instance. Instead, the ploy was to aggravate people’s fears, transform them into terrors. White politicians thus maintained control moment by moment, in ways that served few people’s if anyone’s interests in the long run.

VIII.

“I’d best not linger here.”

The Letter from the Birmingham Motel

In “A Letter from the South: Nobody Knows My Name,” Baldwin recorded his counterintuitive finding that, despite the history of slavery, the demise of reconstruction in the late 19th century, and the modern system of segregated oppression, “the black men were stronger than the white.” Echoing things he’d dredged from his memory and imagination in creating the characters of Florence and Elizabeth in his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, he continued: “I do not know how they did it, but it certainly has something to do with that as yet unwritten history of the Negro woman.”

By 1960 when he wrote “The Dangerous Road Before Martin Luther King” for Harper’s, Baldwin understood how some of the unwritten history was ritualized. He had stayed in Montgomery for a mass meeting led by King the day after the Sunday service at Dexter Avenue. He was scheduled to be in Birmingham for the rest of the week. His letters don’t detail his impressions of King’s sermon from Sunday (October 13) or from the mass meeting on Monday. Likely it took a while for him to absorb it. In any case, as we’ll see, by the time he left Birmingham, Baldwin was in no shape to do much more than survive. Three years later, in “The Dangerous Road Before Martin Luther King,” he recalled the transformative experience in Montgomery:

There was a feeling in this church which quite transcended anything I have ever felt in a church before. Here it was, totally familiar and yet completely new . . .

. . . The Negro church was playing the same role which it has always played in Negro life, but it had acquired a new power.

This new power had gone far beyond the confines of churches and most certainly didn’t emanate from a single leader. It came from relationships that clarified people’s sense of collective purpose and mutual consequence. Baldwin wrote: “It is true that it was they who had begun the struggle of which [King] was now the symbol and the leader; it is true that it had taken all of their insistence to overcome in him a grave reluctance to stand where he now stood.” As Danielle McGuire details in her crucially important work The Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance, by the time King came there, women in Montgomery and surrounding communities had been formally organizing against and resisting racist sexual abuse for at least a decade. So when Baldwin writes “it was they who had begun the struggle,” he’s mostly talking about the women’s movement in Montgomery.

Of course, King was no mere spoke in the wheel. Having talked with him in Atlanta and after watching him “standing where he now stood” in Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Baldwin realized, yes, the “unwritten history” of the Black women’s movement in Montgomery had provided the structural basis and the momentum, but it is also true, and it does not happen often, that once he had accepted the place they had prepared for him, their struggle became abs lutely indistinguishable from his own, and took over and controlled his life.

The basis of that movement had been Black women’s struggle for the integrity of their—meaning one another’s—bodies. At bottom, integrity was collective. That was the key to undoing the great American illusion.

Here, now, with Baldwin’s struggles detailed in part one of this essay in mind, we can begin to see the depth of the question answered in his experience in the Deep South in 1957. Primed by his meetings with Gus Roberts and his mother in Charlotte a few weeks earlier, Baldwin encountered, in King, a radically transformed example of what ceasing to play it safe could mean. Here was someone for whom being delivered from “the prison of [one’s] egocentricity,” being released from the trap of one’s “own dirty body,” was political as well as personal. King’s was a physical as well as a spiritual endeavor. Crucially, this was not a dynamic that could be reduced to individuals.

The basis of that movement had been Black women’s struggle for the integrity of their—meaning one another’s—bodies. At bottom, integrity was collective. That was the key to undoing the great American illusion: the exceptional nation made up of exceptional individuals. For most of his mature career, certainly after The Fire Next Time, Baldwin’s description of the role of poets and artists would paraphrase almost verbatim what he took from witnessing King’s Sunday service in Montgomery. This is exactly why most of Baldwin’s literary and cultural critics consider his mature work his weakest. Some of them are still, in no ways simply, unable to recognize the buried—profoundly gendered and deeply Southern—structure of Black power. And not all of them are white.

Baldwin’s pursuit of personal success, conventional happiness, and that version of freedom had turned to acid the previous year. His collapse had nearly killed him. Now, those illusions were being replaced. In Montgomery, Baldwin witnessed churches, the likes of which he thought he knew, transformed into something actively powerful. The way King and the community mobilized their power presented to Baldwin a model for creative, collective human purpose. He felt he was in the presence of a clarified sense of mutual consequence—a people’s affirmative sense of itself, grounded in their transformed sense of each other—that he’d been groping for as if in the dark. Describing what he’d witnessed, he wrote:

The joy which filled this church, therefore, was the joy achieved by people who have ceased to delude themselves about an intolerable situation, who have found their prayers for a leader miraculously answered, and who now know that they can change their situation, if they will.

The road ahead was long and the route would be in many ways unspeakable. But Baldwin had witnessed evidence of a truly new (but also ages-old) sense of possibility in the making. King, Abernathy, and the community in Montgomery had exposed a profound possibility. The white folks were mostly in disbelief. Some created bunkers of silence. Others prepared for what they considered a racial war. A few would join the movement for desegregation and run their own risks and experience reprisals. Baldwin was clearly moved. He was changed, possibly changed into what he’d always been but, until then, had been unable to become.

Baldwin flew from Montgomery to Birmingham late in the evening following the mass meeting on Monday, October 14, 1957. He stayed in Birmingham for three days, flying to Little Rock on October 19 and making a stop in Nashville before going back to Washington, D.C., to take the train to New York City. No mention of Birmingham appears in essays Baldwin published about his first tour of the South. He wouldn’t write about his first visit to Birmingham for many years. In No Name in the Street, Baldwin recalls a visit by Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, who had been severely beaten outside Phillips High School in Birmingham on September 17, less than a month before. Baldwin recalls that Shuttlesworth came up into my room, and, while we talked, he kept walking back and forth to the window. I finally realized that he was keeping an eye on his car—making sure that no one put a bomb in it, perhaps.

The realization worried Baldwin. After hesitating, he mentioned that he was concerned for the reverend’s safety. The openly outspoken Shuttlesworth, whose wife had been stabbed, whose daughter’s ankle had been broken in the violence outside Phillips High School, and whose house had been bombed on December 25, 1956, was by then a veteran of not playing it safe. Baldwin had fought many intense battles in New York and elsewhere, but in Birmingham he felt out of his depth. He recalls Shuttlesworth’s response:

he smiled—smiled as though I were a novice, with much to learn, which was true . . . and told me he’d be all right and went downstairs and got into his car, switched on the motor and drove off into the soft Alabama night.

Baldwin was staying upstairs at the A.G. Gaston Motel, a modern luxury motel owned by a local entrepreneur. The Gaston Motel would become iconic as the headquarters of King’s movement in Birmingham in 1963. Staying in Room 30, in April 1963, King would decide to march with followers in defiance of Sheriff Bull Connor and an injunction against protests issued from the Alabama Circuit Court. While in jail on April 16, King would write his response to white clergy and other local leaders (A.G. Gaston among them) who were against protests that broke the law, “The Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” King’s letter would become one of the most important documents in the moral scaffold of what would be known to history as the Freedom Movement.

Likely late in the evening of October 17, Baldwin wrote what I call “The Letter from the Birmingham Motel.” Sadly, in the 60 years since he wrote it, Baldwin’s letter has been as obscure as King’s has been visible. The motel stationery on which Baldwin penned his thoughts includes an architect’s detailed rendering of the modern, two-story structure, built in 1954. Modern amenities in the “completely air-conditioned” motel are proudly listed beneath the rendering. Down the left margin, underneath a portrait of Gaston, are photos of the lobby, a bedroom, a master suite, and the motel coffee shop. Certainly there were few Black-owned motels such as the Gaston in the Deep South. Baldwin posted this letter in the accompanying motel envelope to Washington, D.C., from Birmingham in the 9:30 am pickup. It contrasts the comfortable lodgings starkly.

Deeply troubled and unnerved by what he’d seen and heard, and just as much by what he felt and feared in the Southern darkness and silence that surrounded him, Baldwin was at wits’ end when he wrote this two-page letter to Painter. Earlier in the week, he had told his brother he was having trouble sleeping; he said he’d written to ease his feelings. Writing from Tuskegee on October 14, he’d told Mary Painter he was really afraid for the first time; he’d said he had a cold or something like it; he’d suspected it was the result of nerves.

Even by Baldwin’s rather extreme standards, his letter from the Gaston Motel is painfully intense. He opens the letter by confiding that he’s gripped by symptoms of panic and terror; he’s barely holding on. The cold or whatever it was from Tuskegee has worsened, his head hurts, and he is unable to sleep. He’d spent the day walking in the city, talking with people, including a white man who worked for the National Conference of Christians and Jews. This man told Baldwin he was leaving Birmingham, forced out by reprisals in employment, damaged credit, and social ostracism. Too many burning crosses.

He said his wife had miscarried due to the stress of being, as Baldwin puts it, “off-beat.” The man was afraid to leave her at home alone at night. Stories from Black cab drivers, Baldwin writes, were even worse. He thought possibly the acute symptoms of panic followed from his reading from pamphlets and articles, from KKK literature and white citizen’s council reports. In any case, he felt it best that he leave the city as soon as possible. As if to remind himself that not all of life in the US is as it appears to be in Birmingham, he tells Painter he looks forward to seeing her and being in company not so intensely divided by racial warfare. From Birmingham, it appeared to him that no one really cared about the country. If someone did, he wondered, how was such a situation possible?

Giving himself a vantage beyond that particular postage stamp of bitter earth, for a few sentences Baldwin turns to the global, the historical. He tells Painter not even his travels in Germany and Spain after World War II had exposed him to this kind of desperation. This historic perspective clearly fails to raise his hopes in the moment. He wonders if he hadn’t met the likes of those in the mass meetings and mobilized Black churches of Alabama in Germany and Spain because, by the time he arrived, these Black community’s European counterparts had already been exterminated by fascists. Baldwin felt he was touring a prelude to genocide.

In “A Letter from the South: Nobody Knows My Name,” Baldwin recalls his first sight of the red soil of Georgia from the plane taking him to Atlanta: “I could not suppress the thought that this earth had acquired its color from the blood that had dripped down from these trees.” Baldwin’s mind became filmic: he imagined “a black man, younger than I, perhaps, or my own age . . . while white men watched him and cut his sex from him with a knife.” In “The Hard Kind of Courage,” he wrote that images of Southern horror “had been books and headlines and music for me but it now developed that they were also a part of my identity.”

In a way, all this horror had been culture and lore and history when Baldwin left New York on his tour. By the time he wrote those words, however, at least one such image would be disturbingly particular. Baldwin ends his Letter from the Birmingham Motel by informing Painter that the next morning, the dishwasher at the Gaston Motel will take him to meet “the boy” who had been castrated in Birmingham a few weeks before. He is referring to Judge Edward Aaron.

Aaron, who was one year older than Baldwin, had been abducted at random on Labor Day 1957, beaten, and mutilated by a group of notorious KKK-affiliated white men, some of whom had participated in the assault of Nat “King” Cole on stage during a concert on April 10, 1956, in the Birmingham Municipal Auditorium. No record of Baldwin’s meeting has been found to date, but the incident stayed with him. In May 1963, in fact, days after the May 12 bombing of the A.G. Gaston Motel and the uprisings in Birmingham that followed (famous for images of fire hoses trained upon children and teenagers), Robert Stone of Time magazine mentioned the violence in Birmingham and asked Baldwin if he planned to go there. Baldwin responded: “If I’m called, I will go. I don’t want to get castrated any more than anyone else. But I will go.” Time opted not to print the comment. As Baldwin tells Painter in his letter, after the meeting with Aaron he intends to leave Birmingham, a city he takes to be orchestrating its own destruction. In French, Baldwin signals that he’ll see Painter soon and signs the handwritten letter Jimmy.

The density and intensity of Baldwin’s Letter from the Birmingham Motel is unique among the hundreds of his letters I’ve read. It’s the most apt and gripping account of what ceasing to “play it safe” felt like to Baldwin. Written in the dark of night, it figures the extremity of the journey he’d been moved to make and the way he’d kept all his nerves alight and all his senses open. Maybe too open for his own good.

Less than three weeks before, he’d marveled at the silent strength of Gus Roberts and his mother. Still, clearly he wondered how and why they kept to their circumferences of silence. Now, here he was in Birmingham, physically trembling, fearing that the reverend who had just left his hotel room wouldn’t make it home alive. When he’d written from Tuskegee, he’d told David that when he returned to New York this time, it might be the only time he’d ever be glad to see the place.

Baldwin would carry out the rest of his career, and live the rest of his life, in almost constant motion across and between continents. He returned to the South many times, for many reasons. He’d always be returning to the mirror where he’d found “himself reflected” in such angular but undeniable ways in 1957, maybe most of all in the kaleidoscope of people—Southerners young and old, men and women, mostly Black but a few white folks too—who were struggling to remake their world.

Among the array of images, he found in Martin Luther King Jr. a man who’d unlocked the “prison of [his] egocentricity,” a reluctant prophet who’d been summoned into a movement begun by Black women (Rosa Parks lead among them) who collectively sought control over the integrity of their bodies. He found himself connected to a larger body in the process of clarifying what the human power of mutual consequence could mean, and then putting it to the test.

![]()

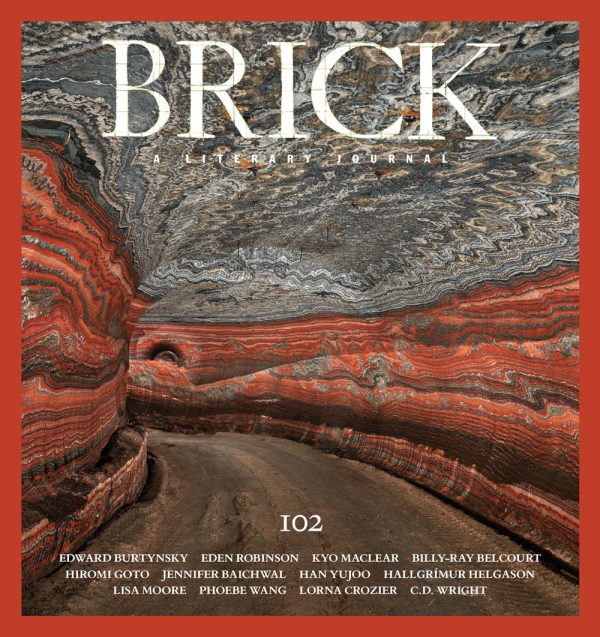

From issue 102 of BRICK. Copyright Ed Pavlić, 2018.

Ed Pavlić

Ed Pavlić is the author of Call It in the Air and Visiting Hours at the Color Line, as well as a novel, Another Kind of Madness. His other books, written across and between genres, include, most recently, Outward: Adrienne Rich’s Expanding Solitudes and the collection of poems Let It Be Broke. He lives in Athens, Georgia, where he works as Distinguished Research Professor of English, African American studies, and creative writing at the University of Georgia.