On Historical Blurring and the Question of ‘What If’

Rachel Barenbaum and Christopher Castellani in Conversation

A Bend in the Stars by Rachel Barenbaum is the story of a scientist racing Einstein to prove relativity. In the chaos of war in 1914 Russia, on the brink of solving the famous field equations, he goes missing—launching his sister on a desperate search across Russia to find him. When she does, she must choose between saving his work and her own future.

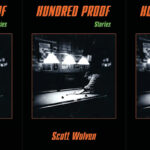

Leading Men by Christopher Castellani is an expansive yet intimate story of desire, artistic ambition, and fidelity, set in the glamorous literary and film circles of 1950s Italy. In July of 1953, at a glittering party thrown by Truman Capote in Portofino, Italy, Tennessee Williams and his longtime lover Frank Merlo meet Anja Blomgren, a mysteriously taciturn young Swedish beauty and aspiring actress. Their encounter will go on to alter all of their lives.

*

Christopher Castellani: It’s so boring to ask you this to start, but I have to because this is the question you’re going to get from every single interviewer, so you might as well start answering it now.

Rachel Barenbaum: [laughs] Ok!

CC: Why did you choose to write about this particular set of characters and this particular real-life event and these real-life people? And how did you first get the idea?

RB: This is actually my Jewish Book Council pitch. I’ll try it out on you.

CC: All right, hit me.

RB: In 2015, I was reading one of those excerpts in Scientific American that said a hundred years ago this month, Einstein was trying to get to Russia to watch an eclipse, to prove relativity, but it’s a good thing he didn’t make it, because at the time, he didn’t have the right math. And if he had gotten the pictures and he had published his math, people would have called him a fraud. And I thought, that is a genius book—what if someone else actually made it to Russia? Einstein’s team was stopped at the border because he was German. Part of my family is Russian, so I’ve always been fascinated with that country and that time period—that’s when my family left. So it just came together from there very easily. I think the lens of what if? is fascinating.

CC: There’s the counterfactual mode of fiction writing: those books like The Plot Against America, and a lot of other books that imagine, what would have happened if we lost the Second World War? or, what if JFK had survived his assassination? There’s a long history of those kinds of books out there, which I didn’t realize until I started delving into this genre, and it does have a very political history. The first stories that were written in the counterfactual mode—or what I was calling “real name writing mode”—the earliest examples go back to the Romans. Shakespeare’s history plays are examples of real name writing: making Richard III a character, and Henry IV. The origins are political, and it’s only recently, in the past hundred years, that writers have been writing in this mode in a way that isn’t explicitly political. And I don’t feel like I had a political agenda for my book, but I’m wondering if you felt like there are political elements in yours? Making this thing happen that didn’t happen—did you have any kind of political agenda when you were writing?

RB: Can you write something apolitical, if it’s a what if? I think, inherently, when you’re writing a what if story, you’re going back because you think something is missing in history, and I don’t know what motivates that—if you want to call it politics or not—but I would call it politics. Certainly in my book, it’s politics. I’m haunted by the idea that we have a huge war every time the next generation forgets what it was to lose people in a war. And I know we have wars going on right now that are awful, but I think a lot of people forget the horrors of World War I and what was happening in Russia. That was the first great war, and I really want people to remember how much the world changed at that moment, because that was the last moment in history when ideas really motivated people more than fear. I want us to come back to that.

CC: One of the things that motivates so many writers in this genre is a redemptive or corrective impulse. Some writers are writing about figures who have not been properly celebrated or acknowledged, as a way of correcting the history, and some people are writing about people who have been misunderstood, as a way of redeeming them. I agree that the corrective and redemptive impulse is inherently political, and so it sounds like, for your book, you were writing this as a way of reminding people of this period in history that is more easily forgotten because World War II came on its heels, and that great war has dominated the cultural imagination more so than the First World War. Is that right, would you say?

RB: For sure. But, also, I believe that people can be moved by ideas. Ideas are powerful. When I was writing the first few drafts, I wanted my main character, Vanya, to be moved just by the need to solve relativity. Why can’t he just be so driven by this need to understand the universe? And I got a lot of pushback on that because people would say, but that’s not enough: he has to be scared for his life; he has to be scared for his family. I think some of that is true, but at that time, in the 1900s, ideas were that powerful. The Russian Revolution came right after that, and I think that we forget today how important those ideas were.

CC: I love that, and I think what you’re coming up against is truth and human nature versus plot and marketability. Those two things don’t always agree with each other. And I agree with you; if you have a character who is motivated by ideas, well, what do we always tell our students? Your character has to want something and want it intensely. It’s your job, not to give them a bunch of other things to want; it’s your job to convince the reader that they want that one thing so badly that they’re willing to risk their life for it, and if it’s to prove an idea or discover something, it’s a little more challenging, but that’s your job as a writer—make that idea so compelling to the reader that we get swept up in it.

The idea that history is not stable, not monolithic, but a collection of what really happened and what has been interpreted as having happened, really compelled me.RB: Yes. Exactly. I’d love to move back to asking about the what if genre, and ask about your what if. Can you tell me about the what if you chose for Leading Men, and talk a little bit about why you were so drawn to your alternate history?

CC: The more I’ve been thinking about this, the more I have been drawn by that corrective or redemptive impulse in order, mainly, to bring Frank’s story into the light—to recognize the man behind the man, to give an identity and a texture to those people who create space for artists. As Williams’s rock, his partner, his—he wasn’t his muse, but Frank created a space for Williams to create his art, and he sacrificed a lot of his own identity, and a lot of his own ambition, in order to do that.

I found that sacrifice compelling on a human level, and I found the idea of what goes into making a great artist interesting on a broader level—the idea that no artist does it alone, that if it weren’t for Frank or some of the other people who were in Williams’s orbit, he probably would have self destructed and not created as much as he did. I wanted to give Frank his due.

And then there was the collision of fact and fiction, with introducing this other character, Anja into it, who is completely fictional. A line that was written about Hilary Mantel I found really resonated for me: someone who was writing a review of her said that historical fiction can be read as less an effort to evade the blur between fact and fiction, than to honestly point toward that blur as a condition of history itself. The idea that history is not stable, history is not monolithic, that history is a collection of what really happened and what has been interpreted as having really happened, really compelled me.

Having a fictional character alongside a real character and having them interact not only seems like an accurate description of how we write history, or how we understand history, but particularly for writers who are constantly having these imaginary friends around us at all times, I’ve come to think of Anja as an imaginary friend that Williams and Frank conjured up. So much of the book is about the illusions that writers live with, or that artists live with, and that we accept as truth in order to survive. Anja functions in that way as well; asking myself that what if of creating her character had that effect—she embodies the illusion that writers have about their characters.

All of that is true, but also the real answer is that—and I’m sure you felt this way too—you have all of these facts that you’re supposed to adhere to, and a timeline, and you had a historical event that functioned as a clock for your book, and gave it a structure and shape, and those are great: having those constraints are, for me, necessary when I’m writing, because otherwise I could go crazy and I wouldn’t know what I was doing, but they also can feel confining. For me, having a section of the book that had constraints, and then another section of the book that had no constraints was the perfect recipe for simply having a—I wouldn’t say an easier, but a more dynamic writing experience. When I was tired of the constraints in the Frank sections, I would dream and play a little bit with Anja. And then when I was feeling too overwhelmed by possibility with her, I would go back to the confines of the historical sections.

How did that play out for you, that merging of fact and fiction?

I balk at this idea that writing is inherently lonely, because I don’t feel lonely when I’m writing.RB: Well, first I want to go back to this idea that you started out with, because I loved this: you said that Frank created the space for Williams to be artistic and to write his plays, and that history, or we, don’t often appreciate that or look at that space. That is fascinating because so many artists need someone as their anchor, and yet in Leading Men Williams still felt so lonely to me, even though Frank was there, and I wanted to know what you thought about that loneliness. Did you feel that?

CC: I’m not in Williams’ head in the book, so whatever loneliness he gave off was through Frank’s eyes—through his interpretation of what Williams was like. Everyone always says that writing is lonely, but even though my characters are imaginary friends, I don’t feel like I’m alone when I’m writing. I feel like I am surrounded by these people. This is what I meant before about writers being able to live in illusions. It’s a complete illusion that these people exist, and yet they’re as real, if not more real, to me than my friends and family. I balk at this idea that writing is inherently lonely, because I don’t feel lonely when I’m writing, and I don’t actually know if Williams did either. I felt like he was exhilarated when he was writing. He wrote every single day, and the loneliness came from having written something and having it be over, and having it maybe not be received as well as it could have been, and feeling vulnerable, and feeling scared, and feeling anxious, and the only way to get over that is to write more. He was constantly writing, and so that’s where all that plays out.

RB: I feel that! The loneliness is not in the writing, because I’m with you: my characters are real to me. But then when I’m done, and then I have this book sitting there in my computer and I have to send it out, that’s the moment of terror—and loneliness.

CC: It’s totally terrifying, and, yeah, you’ll have to do edits, but you don’t have the same relationship with those characters as you do when you’re creating them the first time. They start to, not to be dramatic, but they start to die, and you have to say goodbye to them, and you have to move on. Maybe that’s where the loneliness comes from: we create these people and then we watch them fade away, and then we move on, and that’s a lonely feeling, to be saying goodbye to our friends all the time.

[both laugh]

RB: I love that. I think that’s right.

CC: One of the many strengths of your book, and one of the things I loved about it and find so rare, is how well populated it is. There are so many minor characters—the grandmother, for example—it feels very rich and robust, and it feels crowded. What’s a positive word for crowded? [laughs] It feels like you’re in good company.

RB: It’s funny you say that. My uncle read the book a long time before I sold it, and he said, how do you have so many characters? How do you keep track of all those people in your book? And I said, you know, to me, they’re just like real people. When you’re out in the world, and you’re trying to buy a ticket to get on a train, you’re going to see a conductor, and there are going to be people next to you. I just imagine all these people like you were saying; they’re all real to me, so I see them going through the world and interacting, because that’s what we do.

CC: As strong as your two main characters are, I don’t think only about them. I think about—not the train conductor, obviously, but the secondary characters that are the next tier down from the protagonists. They stand out to me as much as the main characters, like the conniving professor, and the grandmother, and Sasha, the man that Miri rescued. You created this whole world of people, and this is also the question that you’re going to get a lot of the time: how much of it is based on real people, and how much of it is completely imagined? I know you can’t say, 18% is real, but in general, how did you balance that?

RB: I made everybody up except for Einstein. When I wrote the first draft, the book was about the grandmother, Baba, and she was loosely based on my great aunt, who came from Russia.

CC: That’s what I’m remembering, I think, that there was a real person who anchored the book.

RB: She was the only one, and everybody else I just made up. But a very famous author whose name I can’t remember right now once said all of our characters are based on real people and simultaneously made up. We couldn’t write anything real without knowing people and our experiences. So, it’s all fiction—but there must be bits and pieces of people I know sprinkled here and there.

But you also have these characters that are so real.

CC: Yeah, but before I go back to me, because I’ve talked too much, I think it’s a real testament to your book that I don’t think of it as a book in which everyone is made up. Maybe because you have this real historical event, and, again, that clock that is running the whole time, and you do have Einstein, not as a character, but as a real person in the book. It does have that glow of reality, and this atmosphere that if you went to that time and place, you would find those characters. You wrote into reality in a way that felt very convincing. And I think some people are not going to believe you when you say that these characters aren’t real.

The idea of the female doctor, did that come from family history or your imagination?

I wanted a strong woman in the book who was doing something with her life.RB: I wanted a strong woman in the book who was doing something with her life. Not that motherhood isn’t doing something with your life, but most women then were mothers and that was all they did. If a woman wanted to work, she was a midwife of some sort, or in childcare. I love books with strong female leads who are breaking barriers and doing interesting things; that’s just what I’m drawn to. So I invented her, and then I found that there were a couple of real-life surgeons in Russia then, but they had to go to Switzerland and France to get their degrees, and then they came back to Russia to practice. So I made my character a little further forward thinking—she gets her degree in Russia.

CC: You don’t have a medical background, right?

RB: No. Nor am I a physicist!

CC: I just assumed that you had a medical background, or that Miri was based on a real person.

RB: I want to hear you talk about your play within a play.

CC: In my attempt to find a story arc for Anja, in the non-real part of the book, I wanted her to have, not a quest—quest is too strong a word—but a driving narrative, and the option I came up with was that she held onto a play, this lost play, and she felt pressured, or a sort of ambivalence, about releasing it or putting it on. I liked that enough as a plot device. It’s not going to make marketers and editors stand up and be like, ooh, how exciting, a novel about somebody who isn’t sure they want to put on a play. They’re not going to get super excited about that, but I got excited about that laughs and then I thought, it can’t just be a play about anything. It can’t just be some random Williams play that doesn’t relate in any way to the rest of the book, so I realized early on that the play had to be about Frank, and had to be something that Williams was doing as an act of penance for his relationship with Frank, and also something that he was doing to try to get Anja to star in the play and resurrect his career. It had to have these two elements to it, but I was trying to avoid at all costs having to actually write the play.

The idea of writing a Williams play—even a bad Williams play—was very daunting, to say the least. But the more I wrote the book, the more I realized, you can’t be talking about a play and have the play be a big part of the story if you’re not going to give it in its entirety, and it had to add another layer to our understanding of the characters in order to justify it being in the book. And I love when I’m reading a book and suddenly the landscape shifts a little bit, and I’m reading a document, a letter, a play script. And also this idea—this is the last thing I’ll say, I promise—that when you’re in the world of the play, suddenly you’re not in the world of Leading Men, you’re in the world of that play, and I wanted to give, again, another sense of illusion, another sense of what these characters were constantly doing, which was writing plays, going to plays, and living in these made up worlds.

What if dwells in this world of possibility, but possibility also includes danger or destabilization, and people don’t like that.RB: What did your editor think about the play?

CC: He never once questioned it. My agent questioned it; she thought maybe it wasn’t necessary to have the whole play in it, so she suggested that I break it up and just show clips of it, but it didn’t work. It’s funny, I’ve had people who’ve written and said, after they’ve read it, wow, that was a really bad play, and then other people saying, you know, that play was pretty good. [laughs] The reactions to the play have been as polarizing as the reaction to the book itself.

I’ve gotten the most incredible letters from people—the most passionate, generous, tear-stained letters, and reviews of this book, and the absolute meanest reviews, and the meanest, almost personally aggrieved responses to this book. So there’s something very polarizing about it. I think a lot of it has to do with what we’ve been talking about, that people get upset about the blur of fact and fiction; they want it to be one or the other. They want it to be comfortable; they want to know what they’re dealing with. I think that question of what if is an anxious question. What if dwells in this world of possibility, but possibility also includes danger or destabilization, and people don’t like that. They want their history in neat chapters, and they want to know that he was good, and he was bad. And what you said about ideas: ideas are scary too; ideas challenge people.

RB: People want to read a textbook and say, that’s how it happened, and I know everything there is to know, and now let’s move on. This idea that maybe you missed something, or you didn’t understand this, or there was someone else in the background, it’s so unsettling that a lot of people can’t—it’s a visceral reaction to this idea that maybe they missed something.

CC: Exactly. And they want it to be linear. But of course that’s not in any way how life, or history, or relationships work.

RB: People are so surprised when I say Einstein’s math was wrong.

CC: Right, like, no, no, you can’t do that!

RB: Right, like, he couldn’t have been wrong! But he really wasn’t a mathematician first. I’m not saying he was bad at math.

CC: But people don’t want their narrative to be disrupted.

RB: Yes. I get that reaction from people: are you sure he was wrong?

CC: And who are you to say? Where’s your degree?

RB: Right. You’re not a physicist and you wrote this book?

CC: You’re probably going to get articles with headlines like, “When Einstein was Wrong: A Novel by Rachel Barenbaum.” They always want to focus on something melodramatic and controversial.

RB: It’s really sweet that you talk about when I get articles. [both laugh]

CC: Oh, come on, of course you are. It’s going to be awesome. I’m so excited.

RB: I so appreciate knowing that I can send you an email with any panic, or anything. It means so much to me.

I think that my greatest measure of success will be if I can sell my second book.CC: Any time, and not to freak you out, but it’s only going to get worse in terms of the anxiety. The main question is, and you never know, is it going well? You’ll get good reviews—you’re already gotten good reviews—and things will be going along, and your editor or agent will talk to you, but you’ll never have a sense of whether it’s going well. Even if demonstrable things go bad, like you get a bad review, that doesn’t mean things are going badly. And if you get a great review, that also doesn’t mean things are going well. You just don’t know, so you have to accept that. Books that seem like they’ve blown up don’t actually do that well, relatively, and then books that you’ve never heard of are number two on the New York Times bestseller list. You can’t gauge anything; it’s all illusion. The only thing that matters is: you’ll get letters from people, you’ll do readings and interact with readers, and that is real, and that’s what you focus on—those individual reactions that you get from readers. That’s what I’ve found; that’s the only thing that I can control, and the only thing that I know is real. Everything else is an illusion.

RB: I think that my greatest measure of success will be if I can sell my second book.

CC: Exactly. A writer friend of mine, who has published something like 12 books, said, the only measure of it is, did you have a better experience than you did with your previous book? Not sales-wise, but artistically. And, do you have an opportunity to write and publish the next book? That’s the only thing you should think about. Everything else is what it is.

__________________________________

Christopher Castellani’s fourth novel, Leading Men—for which he received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Massachusetts Cultural Council, and the Guggenheim Foundation—was published by Viking in February 2019. Leading Men was a New York Times Editors’ Choice, an LA Times bestseller, and profiled in Publishers Weekly, People, Entertainment Weekly, Interview, Lambda Literary, and other publications. His collection of essays on point of view in fiction, The Art of Perspective, was published by Graywolf in 2016. Castellani is on the fiction faculty of the Warren Wilson MFA Program and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. He lives in Boston, where he is the proud artistic director of GrubStreet, where he has worked for nearly twenty years.

Rachel Barenbaum is a graduate of GrubStreet’s Novel Incubator. In a former life she was a hedge fund manager and a spin instructor. She has degrees from Harvard in Business, and Literature and Philosophy. She lives in Hanover, NH with her husband, three children, and dog named Zishe—after the folk hero who inspires many tales around their dinner table. A Bend In the Stars is Rachel’s debut novel, forthcoming from Grand Central. It has been named a summer 2019 B&N Discover Great New Writers selection.