On Henry David Thoreau’s Ultimate Instrument of Perception, the “Kalendar”

Kristen Case Explores Thoreau’s Meticulous Tracking of Natural Phenomena

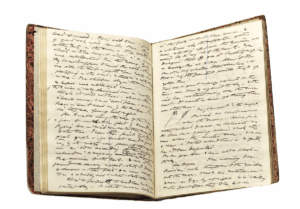

In the spring of 1860, at the height of his intellectual powers and the peak of his political engagement, Henry David Thoreau created something new. Part blueprint for a grand new work, part scientific chart, part picture of temporal experience, this something—which, following a suggestive Journal entry from October 1859 has come to be called his Kalendar—was more a tool than a text.

Comprised of six multipage charts of general phenomena, the Kalendar was an instrument for recording and perceiving not just annual, weather-related phenomena themselves, but also the hidden relations between them—between the skies of one June and the skies of past and future Junes—relations we often feel but can’t quite hold, stuck as we usually are in our own brief moment of linear time.

“Each season,” Thoreau observed in his Journal in June of 1857, “is but an infinitesimal point. It no sooner comes than it is gone. It has no duration.” In other words, loss is fundamental to our experience of time: every moment we experience is already passing away.

His extraordinary Journal is the record of these practices, and the Kalendar is their culminating gesture: the final major endeavor of his life.

However, even as Thoreau acknowledges that “we are conversant with only one point of contact at a time,” he also gestures toward another truth about time—that “each annual phenomenon is a reminiscence & prompting,” that our experiences of the world are connected, pointing backward toward past experiences and forward toward future ones.

This double nature of our experience of time as simultaneously linear and embedded within cycles of related and recurrent experiences is particularly evident in the natural world, where the trembling aspens of June and the frozen lakes of December can be experienced as both fleeting and timeless.

The Thoreau who created the charts of general phenomena was now several years beyond the publication of Walden and still further from his two-year experiment in living in the woods. He lived now in his family home on Main Street in Concord and was an active participant in both family and community life—lecturing at the lyceum, speaking at abolitionist events, and working as a surveyor.

In the early 1850s, he had committed to a pattern of walking (typically for several hours each day) and writing (usually about the previous day’s walk) that he would continue as long as his health allowed, which turned out to be about a decade. His extraordinary Journal is the record of these practices, and the Kalendar is their culminating gesture: the final major endeavor of his life.

The charts of general phenomena derived from Thoreau’s long-held sense that “our thoughts & sentiments answer to the revolution of the seasons, as 2 cog wheels fit into each other,” and his equally long-standing desire to more fully experience and comprehend the complex network of relations—what we would now call the ecosystem—of which he knew himself to be a part. Though Thoreau had for many years been keeping lists and charts of individual observations of the natural world—bird migration times, the flowering and leafing out of trees—the Kalendar was a discovery: a crystallization of his long-developing ideas about time, the natural world, and the nature of perception.

If in 1857 Thoreau lamented that “we are conversant with only one point of contact at a time,” by 1860 he had begun to imagine ways of multiplying those points of contact and perceiving them simultaneously, within a single frame. The frame itself was borrowed from naturalists before him: a simple chart derived from two axes, one measuring time, the other indexing seasonal phenomena.

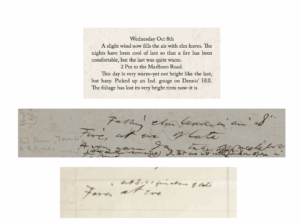

In October of 1859 he had written,

“For 30 years I have annually observed about this time, or earlier—, the freshly erected winter lodges of the musquash along the river side. . . . This may not be an annual phenomenon to you—It may not be in the Greenwich almanack—or ephemeris—but it has an important place in my Kalendar” (10/16/1859, Journal Transcript 30:57).

These allusions—Greenwich almanack, ephemeris, and Kalendar—tell the story of the predecessors of and models for Thoreau’s Kalendar. As a classics student at Harvard, Thoreau was no doubt familiar with the ancient Roman ephemera of Ptolemy—charts tracking the movement of astronomical objects over time. He also knew of the modern versions of these charts published by the Royal Greenwich Observatory beginning in the eighteenth century.

The conspicuous spelling of Kalendar points to John Evelyn’s Kalendarium Hortense, a gardener’s almanac in the classical tradition of Hesiod’s Works and Days and Cato’s De Re Rustica. A more immediate predecessor, the English naturalist Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne—probably the most significant in terms of its influence on Thoreau—contained a naturalist’s calendar, with observations about local species and their first appearances in a given season. Each of these models provided Thoreau with tools for thinking about the intersection of place and time, and for understanding the way the particular species of a place actually construct time: dictating the changes in the landscape by which we mark the year.

During this same period Thoreau created a chart of spring phenomena—February through April, with clearly delineated composite or average dates written along the vertical axis of the chart.

Another model, not for the Kalendar’s formal structure but for the expanded ecological vision it reflects, was Indigenous knowledge. As John Kucich notes, Thoreau was a dedicated student of native cultures but largelyrelied on ethnographic accounts written from a settler-colonial perspective.

However, Thoreau’s participation in the savagist ideology of his time exists alongside his real commitment to learning from Indigenous cultures, and in particular from learning new ways of conceiving of the relationship between humans and a more-than-human world.

In an 1858 Journal entry, Thoreau writes,

How much more conversant was the Indian with any wild animal or plant than we are– and in his language is implied all that intimacy as much as ours is expressed in our language– How many words in our language about a moose–or birch bark! & The like. The Indian stood nearer to wild-nature than we. . . . It was a new light when my guide gave me Indian names for things, for which I had only scientific ones before. In proportion as I understood the language I saw them from a new point of view. (3/5/1858, Journal Transcript 25:107–108)

The passage demonstrates the way Thoreau’s knowledge of Indigenous culture informs one of the driving forces of the Kalendar—Thoreau’s desire to both achieve and represent a more intimate relationship between human and more-than-human life. I follow Kucich in his contention that the two sides of Thoreau’s relationship to Indigenous culture pose a unique problem for Thoreau scholars, and that part of the explanation for this seeming paradox lies in the particular way in which Thoreau sought to make use of Indigenous epistemology in his late natural history projects, including the Kalendar.

Thoreau’s ultimate intentions for the Kalendar remain unknown, however, we do have several suggestive pieces of evidence. The April charts, the first that Thoreau created, contain a column on the far left that includes what seem to be average dates for each phenomenon. This column is empty in the May and June charts, filled in in October and November, and almost entirely empty again in December. The column numbers are often written in pencil, suggesting that they were determined and added at a later date. Much here remains unclear. Why did Thoreau skip the ordering step for certain months? What is the meaning of the superscript numbers next to some dates in this column, particularly in 1861? What does seem clear is that the column represents an initial step toward yet another form of organization. But what?

Here we have some clues, most significantly the “Story of March,” an extended Journal entry from 1860, just before the creation of the charts, in which Thoreau sets out the general phenomena of March in a narrative sequence (Journal Transcript 31:95–109). During this same period Thoreau created a chart of spring phenomena—February through April, with clearly delineated composite or average dates written along the vertical axis of the chart. Taken together, the average column and the two texts from the spring of 1860 suggest that Thoreau was working out ideas for the presentation of seasonal phenomena in narrative form. It seems likely that the charts were originally pieces of a plan for a larger work, perhaps the “Book of Concord” that Bronson Alcott had commissioned him to create for local schoolchildren.

From the posthumously published late manuscript Wild Fruits, we can get a sense of what such a book might have looked like. Organized by date like the almanacs that inspired it, the text likely would have unfolded in the present tense, providing the reader with a real-time narrative tour of Concord through the seasons.

During this same period Thoreau created a chart of spring phenomena—February through April, with clearly delineated composite or average dates written along the vertical axis of the chart.

By the thirteenth of May I notice the green fruit; and perhaps two or three days later, as I am walking perhaps, over the southerly slope of some dry and bare hill, or where there are bare and sheltered spaces between the bushes, it occurs to me that strawberries have possibly set; and looking carefully in the most favorable places, just beneath the top of the hill, I discover the reddening fruit, and at length, on the very driest and sunniest spot or brow, two or three berries which I am forward to call ripe, though generally only their sunny cheek is red.

Unlike the Journal, which documents Thoreau’s experience day by day in linear time, Wild Fruits consolidates experience into a temporality that is at once precise (“by the thirteenth of May”) and general—a habitual present that also encompasses Mays past and future. This is the temporal space of the Kalendar.

Anticipating the way that clock time would be harnessed to control human labor and thought, Thoreau sought an alternative to living that is also an alternative to his culture’s temporal conventions.

In its articulation of an alternative to the forward march of linear time, the Kalendar can be understood as part of Thoreau’s critique of the “restless, nervous, bustling, trivial Nineteenth Century” and its organization of human life. Intimately linked to the rise of industrialization and capitalism, “standard time” or “clock time” began in the early modern period to gain ascendancy over the cyclical, seasonal temporal structures that had governed life in the agricultural societies of Europe in the medieval period.

Thoreau made the link between the “bustling” speed of life in the second half of the nineteenth century and the rise of industrial capitalism and its ever-increasing regimentation of labor: “Where is this division of labor to end?” he asks in Walden, “and what object does it finally serve? No doubt another may also think for me; but it is not therefore desirable that he should do so to the exclusion of my thinking for myself.”

Here, Thoreau perceives the connection between the division of labor and its alienation from intellectual thought and natural processes that would become increasingly common features of working life in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. As Jenny Odell details in Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock, the rise of the mechanized, assembly-line style workplace popularized by Frederick Winslow Taylor was accompanied by deliberate “de-skilling” of the workforce—the active suppression of the worker’s knowledge of the overall process to which they contribute.

Anticipating the way that clock time would be harnessed to control human labor and thought, Thoreau sought an alternative to living that is also an alternative to his culture’s temporal conventions. At Walden Pond, Thoreau designed a life, an economy, outside of the constraints of clock time, a way of being in which “both place and time were changed.” Connecting his own daily habits to the rhythms of the natural world, Thoreau had discovered the plasticity of time. Just as the plants and animals that constituted his world at Walden created the seasons with their appearances and disappearances, Thoreau learned that he, too, could make time through a different mode of living in and recording it. The Kalendar represents the last and most elaborate of his many experiments in temporal arrangement.

Thoreau’s process in creating the charts of general phenomena involved several steps, some of which were adapted from previous chart-making activities. He’d begun tracking leaf fall, first flowering times, bird migration, and other seasonal phenomena in the spring of 1851.

The disciplined recording of alert observation would provide an invaluable record of facts that, when later remembered (or, reconfigured) in relation to other facts, might reveal the direction and nature of change.

As Bradley Dean notes, that same spring the Smithsonian Institute sent to scientists across the country a circular titled “Registry of Periodical Phenomena,” which invited “all persons who may have it in their power, to record their observations [of “periodical phenomena of Animal and Vegetable life”], and to transmit them to the Institution.” The circular lists 127 species of plants, using in most cases both common and Latin names, and asks observers to mark opposite each species its date of flowering.

Though we have no evidence that Thoreau answered the Smithsonian’s call, we do know that he was aware of it, and it seems likely that the project may have inspired Thoreau’s own list- and chart-making practices. The innovation represented by the charts of general phenomena, which Thoreau developed in 1860, had to do with the variety of phenomena observed—and with the inclusion of his own habits of seasonal behavior within their scope.

This inclusion marked a significant shift, not only because it provided Thoreau with the synthetic, comprehensive seasonal view that he sought, but also because it reflected his epistemology: the idea that what mattered was not the distantly observed, objective “fact,” but the fact in relation to other facts—including those pertaining to its human observer. Structurally, the charts mimic those he’d been making of discrete seasonal phenomena for some time, but the creative leap that led to the more inclusive Kalendar charts was profound.

In 1852, he’d written, “I have a common place book for facts and another for poetry– but I find it difficult always to preserve the vague distinction which I had in my mind–for the most interesting & beautiful facts are so much the more poetry and that is their success.” (2/18/1852, Journal 4:356).

Though Thoreau had long desired and moved toward such a breakdown of the fact/poetry binary, his chart and list making remained largely repositories of facts until 1860. Adapting the objective scientific form of the chart to include subjective experience, he arrived at a technological solution to the divide between “scientific” modes of attention to the natural world and his lived experience of interrelation with it. Seeing the months as the charts of general phenomena presented them allowed Thoreau to envision his world as what Darwin called “a web of complex relations” over time.

To compose his charts—those of individual as well as general phenomena—Thoreau relied on his Journal, a storehouse of observations painstakingly gathered through the 1850s. Thoreau was aided in his backward navigation of the Journal by his habit of indexing his text as he wrote—making notes in the back of his notebooks about the page-locations of descriptions of particular phenomena.

Sometime in the early 1850s Thoreau’s indexing habit gave way to a more efficient system of hash marks made in the margins of the Journal next to descriptions of phenomena he might wish to record in a given chart (see fig. 2). This system allowed Thoreau to navigate quickly through the Journal in the next stage of the process: the creation of lists of compelling phenomena organized by year and date. These lists, often scrawled on the back of business letters or other ready-to-hand scrap paper, were an intermediate stage between Journal and chart: a first winnowing of the volume of seasonal observations contained in each month of the Journal. (Interestingly, while lists exist for all months except July, August, and September, Thoreau seems to have only drafted charts of general phenomena for the months of April, May, June, October, November, and December.)

Finally, Thoreau winnowed once again, translating some, but not all, of the list items to his charts of general phenomena, and carefully noting the dates on which each phenomenon occurred in the spaces of the grid. The chain—or more accurately, the network—of textual transmission involved in the production of the charts of general phenomena was complex. Thoreau’s habit was to take field notes on small scraps of paper he carried with him when walking. The next day, he would use these notes to reconstruct the day’s experiences, indexing as he went. When, beginning in 1860, he began drawing up the charts, he consulted the indexes of the many volumes of his Journal, then created the yearly lists, then transferred this information to the charts. Field notes, Journal, hash marks, lists, charts—a textual ecosystem. (See fig. 3 for a partial illustration of one such chain.) H. Daniel Peck observes,

By the fall of 1851 the Journal is already what might be called a material memory, a book deliberately conceived to “keep” time by enlarging the temporal view of reality through the process of cross-reference. Increasingly, this process becomes Thoreau’s major strategy for translating facts into truths—the imperative first publicly proclaimed in his early essay “A Natural History of Massachusetts” (1842). Facts would, that is, gain spiritual significance through their gradually revealed placement along the span of time. The disciplined recording of alert observation would provide an invaluable record of facts that, when later remembered (or, reconfigured) in relation to other facts, might reveal the direction and nature of change. When the past was viewed in this way—and viewing is indeed the right word—it might become possible to “see” time, and to see it whole, as a full matrix of past, present, and even future.

To combat the fatigue that invariably set in during my long afternoons of reading and writing, I took walks through the woods and, returning to the desk in my small study, drew maps of the roads and fields and trails along which I had walked.

The charts of general phenomena never became the “Book of Concord.” Thoreau charts the spring of that year with enthusiasm, then apparently sets the project aside. In December of 1860, Thoreau contracts a cold, almost certainly exacerbated by underlying tuberculosis, from which he never fully recovers. He ventures west to Minnesota that spring in an effort to heal his lungs, but to no avail. By late summer he is back in Concord, and by fall it seems clear there will be no recovery. It is at this point that the seriously weakened, mostly bedridden Thoreau takes up the Kalendar project again, charting the months of October, November, and December.

I first encountered the charts of general phenomena as a graduate student living in a small rural town in upstate New York. At the time, I was struggling with what felt like the meaninglessness of my academic work, which I perceived as impossibly distant from the reality of the world in which I found myself. To combat the fatigue that invariably set in during my long afternoons of reading and writing, I took walks through the woods and, returning to the desk in my small study, drew maps of the roads and fields and trails along which I had walked. These activities were immensely relieving to me.

Exhausted from looking for meaning in philosophical and literary texts, I stepped out into a world in which meaning simply was: where every new flower or leaf that presented itself to my eyes seemed to repeat its own singular name. The names themselves were poems—hemlock, white pine, trillium, Sawyer Pond Road—and I began to work to know more and more of them, and to track how they changed over time. The maps I drew were not objective—they did not reflect the points of the compass.

Starting in one corner I drew the way I walked: first here, to the stone wall, then left, then here, to the break in the trees, then right at the path. When I discovered Thoreau’s charts of general phenomena in H. Daniel Peck’s Thoreau’s Morning Work, I felt an immediate sense of recognition. Thoreau, too, had felt and tried to represent this way things had of showing themselves, of saying their own names, of speaking to us. And Thoreau, too, had made maps that included himself, his own way of feeling and seeing the species that surrounded him and made his world.

“I think that the man of science makes this mistake–& the mass of mankind along with him,” he wrote in his Journal in 1857, “that you should coolly give your chief attention to the phenomenon which excites you–as something independent on you–and not as it is related to you. . . . With regard to such objects I find that it is not they themselves–(with which the men of science deal) that concern me. The point of interest is somewhere between me & them (i.e. the objects)” (11/5/1857, Journal Transcript 24:610).

Here was a new model of meaning, one according to which my meandering, hand-drawn path through the woods was as real, as true, as the digital map of those woods I can call up on my phone from 376 miles northeast and more than a decade in the future.

My encounter with Thoreau’s charts of general phenomena reorganized my thinking, allowing me to envision a mode of scholarship from which my life—the day and its weather, the patterns and demands of domestic life, my feelings—was not excluded from the picture. Moreover, it encouraged me to understand myself as a seasonal creature, one among many who sought warmth in winter and shade in summer. I began to see the world as more- than-human, and meaning itself as a collective undertaking involving many human and nonhuman actors. I began not only to see but to feel the relationships between my being and the climate in which I lived.

In the years in which I have been working on these manuscripts, the seasons of my own life have changed the eyes through which I look at them, and the meanings they offer. In the wake of two important losses in my life, the charts began to speak to me of Thoreau’s grief, and of the way mourning thickens and reorganizes time. As I suggest in the second half of this book, the Kalendar became, for Thoreau, a means of living with loss—including the impending loss of his own life. As work by Richard Primack has dramatically illustrated, Thoreau’s charts of seasonal phenomena are also linked to larger, more collective losses.

As the realities of the climate crisis and mass extinction become ever more apparent, we find ourselves looking for ways to grieve what is lost while continuing to love the world that remains to us in the time that remains to us.

In March of 1856, Thoreau wrote the following Journal entry, in which he laments the “maimed & imperfect nature” with which he is intimately connected:

I spend a considerable portion of my time observing the habits of the wild animals my brute neighbors– By their various movements & migrations they fetch the year about to me– Very significant are the flight of geese & the migration of suckers &c &c– But when I consider that the nobler animals have been exterminated here–the cougar– panther–lynx–wolverine wolf–bear moose–deer the beaver, the turkey&c &c–I cannot but feel as if I lived in a tamed &, as it were, emasculated country– Would not the motions of those larger & wilder animals have been more significant still– Is it not a maimed & imperfect nature that I am conversant with? . . . –I am reminded that this my life in Nature –this particular round of natural phenomena which I call a year–is lamentably incomplete– I listen to concert–in which so many parts are wanting. . . .I take infinite pains to know all the phenomena of the spring, for instance–thinking that I have here the entire poem–& then to my chagrin I learn that it is but an imperfect copy that I possess & have read–that my ancestors have torn out many of the first leaves & grandest passages–& mutilated it in many places. (3/23/1856, Journal Transcript 20:166–67)

As Rochelle Johnson has observed, this passage registers a haunted grief for an ecological wound that has only deepened with time: “Like many of us, Thoreau knows he walks with and among the disappeared nonetheless still there. His world is replete with ghosts—each missing mammal, each vanished species, each shrunken stream still present, apparitions felt as he moves through space and time. He walks amid them. Even through them. Presences in absence. Sounds of silence.”

The entry registers both grief and intimacy, both loss and love. As the realities of the climate crisis and mass extinction become ever more apparent, we find ourselves looking for ways to grieve what is lost while continuing to love the world that remains to us in the time that remains to us.

Throughout his life, Thoreau was steadfast in his commitment to living a meaningful life, to remaining awake to his own experience, and to honoring the wonder of the world in which he lived. In his last year of life, he found ways to maintain this state of reverent alertness, even as he recognized the depth of his own losses and the losses sustained by the more-than-human community in which he lived. The Kalendar Chronoception—our sense of the passage of time—is both deeply internal, keyed to the operations of entropy in the cells of the body, and thoroughly collective, connected to diurnal and planetary cycles, social calendars and the shared rhythms of cultural life. As Barbara Adam writes, we experience time neither as an arrow nor as a recurrent cycle but always as both:

There can be no un-ageing, no undying, no un-birth. We can relive past moments in our lives but we cannot reverse the processes of the living and material world. We know the unidirectionality of time from geological and historic records, from physical processes involving energy exchange, from the irreversible accumulation of knowledge, and from the fact that people and things get older and never younger. We know that the sequence of the diurnal cycle goes from dawn to midday to dusk to night and never backwards from dusk to midday to morning. These examples demonstrate that cyclicality and irreversible linearity are not, as so frequently asserted, the dominant time perceptions of traditional and modern societies respectively. Rather they are integral to all rhythmically structured phenomena.

Implicit in this understanding of the double nature of our sense of time is the complex way our individual senses of the passage of time are linked to those of other species and to physical processes of regeneration and decay that govern that material world. Recent psychological studies on the experience of awe suggests that the expansiveness associated with this state is connected to our experience of time, and in particular with a feeling of temporal expansion. The more fully we engage with our felt experience of time, it seems, the more deeply we learn both lessons: that our experience of time is surprisingly manipulable, and that we are powerless to turn the arrow.

Thoreau’s Kalendar, in its attempts to integrate human and more-than-human timescales and to extend moments of wonder at the abundance of the natural world, exemplifies the power of a radically expanded conception of time. As an elegy to a life lived in nature, it is also a testament to the irreversibility of time’s arrow.

I hope that readers of this book will conduct their own investigations, following the Kalendar’s numbers back to the Journal entries to which they point and discovering their own constellations of meaning. The transcriptions published here can also be found at the online home of Thoreau’s Kalendar: Thoreauskalendar.org.

Here you can follow links from each Kalendar date directly to the relevant Journal entries, walking backward in Thoreau’s footsteps, and moving, as he did in his final months, between the seasons of his life. I have made such journeys myself countless times over the past decade, and doing so has taught me to think differently about my life’s own seasons. The arrow of time demands that we live also in its circles, in the slow time of wonder and in the wide orbit of our planet. I hope readers will be inspired by Thoreau’s slow, devoted attention to his world, and by his relentless creativity in reimagining the time in which he lived. May we find in his example the courage to reimagine our own.

__________________________________

From Henry David Thoreau’s Calendar: Charts and Observations of Natural Phenomena. Used with the permission of the publisher, Milkweed Editions. Copyright © 2025 by Kristen Case.

Kristen Case

Kristen Case is the introducer to the newest edition of Walden and Civil Disobedience (Penguin Classics| On-sale June 13th, 2017) and the author of Little Arias (New Issues Press, 2015). She directs the New Commons Project at the University of Maine at Farmington.