On Grit: How Cheryl Strayed Learned to Ride Into Battle

The Author of Wild Talks to Debbie Millman

You could say that Cheryl Strayed is very adaptable.

Her memoir, Wild, was adapted into a movie starring Reese Witherspoon. Another book, Tiny Beautiful Things, was adapted for the stage by Nia Vardalos and Thomas Kail. Tiny Beautiful Things itself was adapted from an advice column she once wrote called “Dear Sugar.” And that advice column has ultimately been adapted into a New York Times podcast, “Sugar Calling.” To talk about it all, I was joined by Cheryl from her home in Portland, Oregon, where she was isolating with her husband and two teenagers during the Covid-19 pandemic. We spoke about healing our parents’ wounds, going on long difficult journeys, and how to write “like a motherfucker.”

*

Debbie Millman: You recently said that the pandemic has made it clear to you that you are a writer first and foremost. Was that ever really in doubt?

Cheryl Strayed: No, but one of the things that happened after Wild became a bestseller is I suddenly had so many opportunities that were not writing. I now have a very active career as a paid public speaker. Much to my surprise, I’m good at it and I enjoy it, so it got really easy to say “yes” to talks. I say “no” to a lot, too, but it became this thing I could do to earn money and to feel I was doing interesting and important work in the world. It’s not a replacement for my writing, but sometimes it’s a little easier, like, “Oops, I can’t write today because I have to fly to Dallas to give a talk.” Now, all of my public engagements have been canceled. So, it’s, “Okay, back to my origins. I’m going to write my way out of this.”

At first I was in denial about the pandemic; I decided it would last about eight weeks. Then, as the weeks passed, I realized I had to do the thing I have advised others to do many times when they feel powerless: to surrender and to accept. Accept what’s true. I’m trying to accept it and let go of the future.

DM: Let’s go into the past a little bit. You were born Cheryl Nyland in Spangler, Pennsylvania, and moved to Chaska, Minnesota, when you were six years old. Shortly thereafter, your parents got divorced. In addition to the time after your mother died, it seems as if those years were some of the darkest of your life. Did you realize it at the time?

CS: That’s such a great question. I did realize it to the extent that a child can. I was born into a house of extremes. On one hand, I had this mother who was very loving and warm and optimistic. I have a sister who’s three years older and a brother who’s three years younger. My mother always communicated to us a sense of wonder and love and light. The beautiful things. But we were living in a house that was, frankly, terrifying. My father was violent and abusive. He was emotionally abusive to all of us. He was physically violent to my mother. My brother and sister and I all witnessed horrifying things, things that I never witnessed beyond that as an adult.

There will be times in life when you need to ride into battle, and you need to teach yourself how to do that.

As a little child I saw my mother being beaten by my father, my mother almost killed by my father before my eyes, my mother being raped by my father. So my perception of those years is definitely one of fear and sorrow and darkness. But because that was my life, it wasn’t until my mother finally escaped my dad that I realized, “Oh, this is what happiness is. This is how it should be.” We were very poor and lived with a lot of chaos and disarray but also a lot of light and joy and fun—and no longer being under the weight of that fear you have when you live with somebody who’s abusive.

DM: You’ve written, “The father’s job is to teach his children how to be warriors. To give them the confidence to get on the horse, to ride into battle when it’s necessary to do so. If you don’t get that from your father, you have to teach yourself.” What is the biggest thing you had to teach yourself?

CS: The biggest thing is that I’m okay in this world. There will be times in your life when you need to ride into battle, and you need to teach yourself how to do that. If we didn’t get that essential sense of self-worth from both parents, we need to reckon with that in our adult lives. I had to heal many things, but the biggest one was that, at the deepest place within me, I had to learn to believe in the power of my own resilience and my ability to survive and persist. I think that’s what parents give us, if they love us well. And if we don’t get that, we have to find it ourselves in the world.

DM: As I was rereading Wild and watching the movie again, I got the sense that your journey was one of finding out if you could rely on yourself.

CS: I think that we all need to do that. Obviously, somebody like me, who had a father who was abusive and a mother who died—I was really an orphan. But I think that’s part of the human journey. Even my own kids, who are loved and secure and living in a very happy home—part of their journey is going to be finding their way and finding their strength and courage. It wasn’t until after I wrote Wild that I understood that with that hike, I’d given myself my own rite of passage. Those rituals are what we’ve done as humans throughout time, across every culture and continent. We don’t do that so much anymore, and it’s a loss. Most of us would benefit from being asked to find out who we really are by being put in uncomfortable or challenging circumstances.

DM: I came across a couple facts about you that were wonderfully surprising. When you were 13, you moved to Aitkin County, in northern Minnesota, which was very rural. You lived in a house with your mom and your stepfather. They built the house, and for many years the house didn’t have electricity or running water or indoor plumbing. But despite all of this, you were a high school cheerleader and the homecoming queen. You were an overachiever from day one.

CS: We lived in a one-room tar-paper shack for the first six months while we built a house for ourselves. It was a lot of work, and it was incredibly difficult, and I was a teenager. I wanted to be pretty and popular and not associated with going to the bathroom in an outhouse or taking a bath in a pond, which is what I did. My rebellion in my teen years was to be a version of myself that I wanted to be—to project a sense of success, and grace, and togetherness. I wanted to be popular because to be popular is to be loved.

DM: You went to the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, and for your sophomore year you transferred to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where you studied English and women’s studies. What did you want to do professionally at that point?

CS: When I was a freshman, I majored in journalism. I thought that I could funnel my desire to write into journalism because it’s the job where you can actually get paid to write. When I transferred to the University of Minnesota, I majored in journalism, but I took a class with the poet Michael Dennis Browne and everything absolutely exploded. I thought, “I have to trust this.” So I switched majors and became an English major. I thought I’d become a great American writer. I was ruthlessly committed to following through and doing it until I succeeded. As I say these words, the female in me is thinking, “Don’t say you want to be a great American writer because that seems cocky or that you’re bragging.”

“Why do we self-destruct when we feel like we’ve been ruined? It’s a signal to the people around us that we’re saying, ‘Help me.’”

But I’ll tell you, that’s the thing that got me through—the intention, the plan, the ambition. I had to be an absolute relentless warrior and a motherfucker on behalf of my own self as a writer.

DM: Write like a motherfucker, right?

CS: That’s right.

DM: That reminds me of that little mantra you had while you were on your hike, “I’m not afraid. I’m not afraid. I will not be afraid.”

CS: And when did I say, “I’m not afraid?” When I was afraid. Even to this day, writing is so hard for me. I still have to be a warrior and a motherfucker. I still have to say, “Cheryl, you can do this. You’re going to do this, and you are not going to give up. You’re not going to be second. You’re going to go all the way to the finish line.”

DM: In March 1991, when she was 45 and you were 22, your mom died of cancer. You’ve said that your mother’s death was in many ways your genesis story and the start of what you called your wild years. Using drugs or having a lot of sex or any sort of reckless behavior was about trying to find love. Why do you think we hurt ourselves when we’re hurt?

CS: Why do we self-destruct when we feel like we’ve been ruined? It’s a signal to the people around us that we’re saying, “Help me.” It’s also a test. Is there anyone out there who loves me enough to help me? In my case, I also interpret it this way: There was this mythic division in my past between the good mother who’s been taken from me and the bad, dark father who abandoned me. If I can’t be the woman my mother raised me to be—that ambitious, generous, light-filled person—maybe I can be the junk, the pile of shit, the darkness that my father nurtured in me.

There was something that I had to figure out about those primal relationships that I had to rage against and understand and revise. A lot of people who’ve written to me as Sugar—they write to me with a problem, but really the problem is that deep, deep river that’s flowing beneath all the troubles, that subterranean channel that is your parents. Those early stories you received, your losses and your gains and your wounds that you have to heal. And sometimes healing is an ugly thing. For me, I had to pass through everything. When I saw that I was going to lose everything after my mom died, that’s when I turned to heroin. That’s when my response was, “Okay, if the house is going to burn down, I’m going to burn the whole land down.”

The hard thing about that is, of course, some people stay there. They get lost there. They’re walking through the ashes forever. I’m so grateful that that wasn’t my fate. I had to do that stuff in order to realize that I wasn’t the person my father raised me to be. My father didn’t raise me. I was the person my mother raised me to be. That’s why I said that so much of that stuff was about love: I realized that I was trying to show the world, “Listen, this amazing woman is gone, and I am suffering.” I wanted to, with my own life, demonstrate how gigantic that loss was. And what I realized is the only way I could do that was to make good on my intentions. To be the woman my mother raised me to be, as I said in Wild. I would have to live my life and try to honor her with it. And what’s so crazy and cool and beautiful about that is—I did. People all over the world know my mom’s name.

DM: You brought her to life through your words, and she brought you to life through her life.

CS: I was the same age when she died as she was when she was pregnant with me. So I lost her at the same age that I came into her life.

DM: You were 26 when you embarked on your solo three-month 1,100-mile hike along the Pacific Coast Trail. For people who are considering taking this same hike, what advice might you give?

CS: Well, go. Whether it’s the same hike as mine or any long hike—if you have any desire to do this, do it. Okay? I’ve talked to so many people who have taken long walks and long hikes, and all of them say, “That’s the best thing I ever did for myself.” Because walking, especially walking a long way for many days on end, is a deeply challenging thing. You gain a sense of your own strength and your own ability to endure difficulty, monotony, pain. What happens on the outside, one foot in front of the other, also happens on the inside. I love this idea of the body teaching us what the soul and the spirit and the heart need to know. And that’s what happens on a long walk.

DM: As I was rereading the book and watching the movie again, I thought that it was very likely the last moment that we weren’t all walking around checking our emails and texting on our cell phones. It seems unimaginable to me to consider hiking 1,100 miles in near solitude with my phone off the entire time.

CS: This was 1995. It wasn’t until I was midway through Wild that I realized, “I’m actually writing a historical memoir about a world that is now past.” Our experience of the wilderness is now one where, first of all, we can research everything online. I prepared to the extent that I could, but there wasn’t the Internet then. I went to the Minneapolis Public Library and said, “What books do you have on the Pacific Coast Trail?” They had one, and it was the book I already purchased at REI. It wasn’t like information was available—you just had to go and see how it was. And I was absolutely alone.

The first eight days of my hike, I didn’t see another person. There was no way to contact anyone except if I came upon a payphone or if I sent a letter. I’m so grateful that I took my hike during that time because I think had I not done that then, I would have spent a lot of time tweeting at people.

DM: And Instagram, right? With all those great pictures you took.

CS: Yes, and getting feedback from people and not just sitting in my solitude. The thing about deep solitude is it’s just you and there’s nothing to do but reckon with yourself. There’s nothing to do but allow memories to emerge. By the time I was finished with my hike, I felt like I had thought about everything I remembered in my whole life, every relationship, every person. What a therapeutic experience.

DM: Monster was the name of your backpack, which at its heaviest weighed nearly 70 pounds. Even at its lightest, it was 50 pounds. You’ve said that the act of remembering your suffering can become pleasure afterward. How so?

CS: I call it retrospective fun. This is also advice I’d give someone wanting to take a long hike or any kind of journey: You have to acknowledge that often the best things we do are painful and complicated and difficult and exhausting and require us to be out of our comfort zone. If the journeys we take are exactly how we imagine and everything is idyllic and blissful, we would think, “Yeah, that was fun.” But there’s no texture to it.

DM: No grit.

CS: No grit. The grittier an experience is, the more it teaches us. We never forget the lessons we learned the hard way. I began a backpacking novice. I became a backpacking expert. I thought that I couldn’t do that, and I did. I said to myself over and over again, “I can’t go on. I can’t.” And I always did. And then that becomes part of who you are. Ten years later, you’re in labor—as I was trying to give birth to my eleven-pound baby boy—and I was thinking, “I can’t do this.” And the deepest voice in me said, “You know you can.”

DM: While you were working on Wild, you also started writing your advice column, “Dear Sugar,” for The Rumpus. I know you’ve referred to self-help work as intellectually mushy. In Wild, you weren’t giving advice, but people have read it that way.

CS: When I was writing Wild, it never occurred to me that anyone would experience it as inspiring. I was just trying to write the truest, rawest story about that experience, about my grief, about my finding my way on this long walk I had in the wilderness. Even with Torch, I realized after it was published that people were experiencing it as a lifesaving book. I guess that doesn’t really surprise me because that’s what I’ve taken from literature too. That’s what I meant when I said books are my religion—I felt saved by them. I felt seen by them—in Jane Eyre, in Alice Munro’s short stories. There I am in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. There I am in Mary Oliver’s poems. I didn’t intend for my books to be self-help. When Tiny Beautiful Things came out, it was in the self-help section of many bookstores. I saw that and thought, “What?” I think of myself as an accidental self-help writer because “Dear Sugar” columns are self-help, and yet they are also literature.

DM: You’ve been at a crossroads now as different opportunities have come your way. You’ve stated that you think the things that mean and matter the most come down to one question: Do you really want to do it? So, how do you know when something is the thing you really want to do?

CS: For me, it’s when I feel like I can create something that’s larger than me. If I write a book and not only is it a deep and true expression of some deep and true things I want to put into the world, it also becomes something that is meaningful to others. That’s a big thing to contribute to the world. If this mission is fulfilled, will it extend beyond my small little life?

DM: What is the thing you want to do most next?

CS: Finish my next book. I am ready to do that. Wild and Tiny Beautiful Things were published within four months of each other in 2012. And basically my life since was like a volcano.

DM: Yes, movies and Oscars.

CS: I had the movie and the stage adaptation of Tiny Beautiful Things, and I was involved in the podcast and the public speaking career. Also, the kids. During all this time, I have these two little kids, who are now fourteen and sixteen. I am now ready to sit there and write my book. That’s what I’m doing, and I really want to do it. I’m also afraid and doubtful and scared. I’m all the things I am when I’m writing, which means I’m writing my next book.

_______________________________________

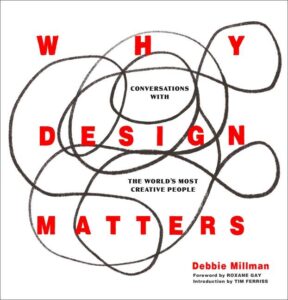

Excerpted from Why Design Matters by Debbie Millman. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Harper Design. Copyright © 2021 by Debbie Millman.

Debbie Millman

Debbie Millman is an American writer, educator, artist, curator, designer, and host of the podcast Design Matters.