On 'Good Men' and the Vague, Low Standards Required

to Be One

Abi Maxwell Considers the Long Reach of a Teenage Crush

The first time I fell in love, I was 14 years old, working nights and weekends as a ski instructor at the local mountain that had one chairlift and one rope tow. He also worked there, and he didn’t love me back—or at least I hope he didn’t; he was 25. Saying it now, as an adult, feels horrifying, though for years I stood firm that he was a good man and there was nothing particularly sinister about the relationship. He picked me up on the way to the mountain, and drove me home at night. We never actually had lessons to teach, so we spent our time riding the chairlift and skiing together. Sometimes, we would talk on the phone. He even made me a mix tape.

Now, though, that phrase, good man, strikes me. Why not good person? Once, soon after my son was born, I stood in the kitchen with my aunt and friend while outside the dads tended the bonfire and probably smoked a joint. “He’s such a good dad,” my aunt pointed out, indicating my husband. True, but what exactly was she referring to? That he interacted with his child? That he, like a mother, loved his son? And why that precise moment, while I stood there, utterly sleep-deprived, bouncing our infant, keeping close watch on what I ingested so that my milk would nourish him? Good man, I’m afraid, has that same low standard as good dad; when I was 14, that man was good because he never touched me, though he had ample opportunity to do so.

While on the chairlift, we would talk a lot about music. In my family, the men were readers, and I would have done better in that realm. I read Hemingway and Steinbeck, both gods to my father and brother. I had spent my childhood reading every dog novel my brother could get his hands on. I had even asked him, at one point, if there was anything else out there to write about. “It’s all boys and dogs alone in the woods,” I remember telling him. But my brother confirmed what I had already gathered: boys and dogs alone in the woods were unsurpassable, and if I was smart I would recognize that.

The man I skied with, though, seemed to take my opinion seriously; at home, my brother taught me what to like, but at the ski area that man asked me what I liked. Once, on the chairlift, after I listed the music I had learned from my brother, I pointed out that no musicians or even writers that I loved were girls (I would not have dared say women). “Boys are just better,” I said. I can still see the dim glow from the trail lights in the moment I said that, can hear the flat scrape of my skis against each other. By that point in my life, I already knew that smart was my path, as I did not have the sort of mother to teach me to be pretty. It was a flippant thing that I had said, but also one I believed to be true, and with it my worst fear arrived: because I was female, my intelligence could only ever take me so far.

I remember thinking that I had changed my name to that of my husband’s, that I now had a literal mark committing me, at least on the outside, to the role of a good woman.

I work part-time at a public library now, and one day while I sat at the circulation desk thinking about how stuck I was in my novel, and how I would never, ever, write my way out of it, a man walked in on his way to the boiler room to diagnose and fix a problem with the sprinkler system. “Oh my god,” I said, and stood up. It was the man I had loved. I grabbed the keys for the boiler room and led him there. I unlocked the door and then turned, looked in his eyes, said a real hello. He was older and heavier and just the same. He spent that day going back and forth past my desk. Once in a while he would stop and talk to whoever else was gathered there, and I had the uncanny sense—just as I had all those years ago—that as we contributed to the conversation, only I understood what he really meant, and he what I really meant. Eventually, I tracked him down outside, asked him about his life, told him about mine. I told him I was a writer, and somehow mentioned that I rented a tiny office. It turned out that the office he worked in was just 50 feet from it.

A few weeks later, he came to visit me in that small, dirty office that was my absolute sanctuary. I rented it because I had a young child at home, and needed silence. That fact also meant that every moment there was stolen time, and I never had enough. And yet I let him come to my office, let him steal my time. He sat in a chair across from me and told me more about his life. I remember thinking as he spoke that I had changed my name to that of my husband’s, that I now had a literal mark committing me, at least on the outside, to the role of a good woman, as if my sexuality were so dangerous, as if I could not be trusted with it. And what if I had not had that mark? Surely the shape of me, in his eyes and my own, would remain unchanged—I would still be a mother, still be a wife. But would it have been easier to shrug off that image of a good woman? I had never aspired to that; to me, it looked like a lot of warm food and compliance. Yet as I sat with him, my name made it clear that I was no longer the independent person who had loved him. He, though, if he had been married, would still have the same name, would still be the same person. He could be trusted. And if he couldn’t, what difference would it make?

He was a few years from 50 on that afternoon, but he told me about his 40th birthday party. He told me about what it had been like to work the same job for all these years, and what it might have been like if he’d followed his dreams. He told me he’d been married and divorced twice, had never had children, and now lived with his girlfriend and her daughter. I gave him a hug before he left, and he mentioned that his girlfriend would never let us be friends. I closed the door after him, and stood there thinking of how easily I had slipped into that quiet and agreeable role, and how sickeningly well that role could work.

Yet it occurs to me now that like trauma, the necessity for male attention is so practiced that it too must be remembered in the body.

As summer went on, I found I could no longer focus in my office. Instead, I looked out the window to see if he went by. I took a walk to increase the chance that we would cross paths. I had no interest in or attraction to this person who likely could not even meet the criteria for good man anymore, and at first I thought the momentary return to obsession must be connected to the way that trauma is remembered in the body. Yet it occurs to me now that like trauma, the necessity for male attention is so practiced that it too must be remembered in the body.

Recently I spent a week in my mother’s house. There, at the back of the closet of my childhood bedroom, I found a box of all my old journals. I was disgusted to see that for four years they were about him, and if they weren’t about him they were about some stand-in crush to suppress my love for him. I was tempted to burn the journals, to save myself the humiliation of dying and then having someone read them and discover what a stupid girl I had been. But now I am wondering what else I could have expected of my old self.

If my mental state suffered during that recent summer that I ran into him, at least it had a function; in that mysterious way that fiction so often works, I realized that the dark place I had sunk into was just where the teen girls of my book needed to go. They are young and obsessed, just as the patriarchy trained them to be, yet miraculously they avoid something that I never could: shame. They would not have said that thing on the chairlift, because despite what society told them, being female never made them less sure of their desires, their worth, or their intelligence.

I was much more typical. That night on the chairlift, I understood that because of my anatomy, I was destined to be less. If good man means one who does not take advantage of his power, good woman clearly means one who knows her place. It is no surprise to me now that my teenage self recognized that void. It’s what Claire Dederer wrote about in her brave memoir Love and Trouble: I knew I couldn’t be a man, so the next best thing was to make sure I was adored by one, by any.

It’s an odd feeling, to look back on your former self and wonder about your agency. My characters experience it, too. I, like them, keep asking the same question: If the bulk of my formative experiences were created by the patriarchy, are they still mine?

__________________________________

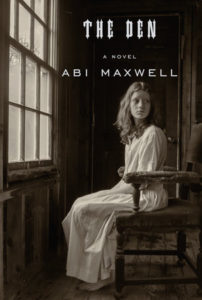

The Den by Abi Maxwell is out now via Knopf.

Abi Maxwell

Abi Maxwell is the author of the novels Lake People and The Den. After graduating from the writing program at the University of Montana, she spent many years working in public libraries, and she now works as a high school librarian. She is a dedicated advocate for the rights of transgender youth in her state and frequently testifies in front of the legislature on their behalf.