On Finding the Book That Returns You to Your Body

Dodie Bellamy Reads Paula Modersohn-Becker

One summer in Los Angeles, Hedi El Kholti—my and Marie Darrieussecq’s editor at Semiotext(e)—gave me this book. “Here,” he said as he handed it to me. “I love this book.” When I returned to San Francisco I threw it in a pile and forgot about it. But then it somehow moved to the bathroom and I was hooked. Like many Victorians in San Francisco, my bathtub and toilet are in two separate rooms. The toilet room, no bigger than a closet, along with my office, is on an enclosed back porch. As I sit at my desk, the bathroom is behind me. If someone’s visiting and wants to use the facilities, I need to get up and go to another room, to give them some privacy. There’s a litter box wedged in next to the toilet, and sometimes one of the cats will sit in the box beside me, doing their business, and I feel like such an animal. They don’t understand most of what I do, but this they get. Marie Darrieussecq: “We work and we are bodies.” Throughout all my writing the shadow of dejecta looms.

Being Here Is Everything is very much about the body, the aliveness of Paula Modersohn-Becker at the turn of the 20th century, and the bodies of the women she painted, especially the nudes, finally freed from the imposed metaphors of “centuries of the male gaze.” Modersohn-Becker’s nursing babies look like real babies, and they’re held the way real women hold nursing babies. Since Modersohn-Becker died of complications from pregnancy, all these images of mother-child fusion are infused with tragedy. Darrieussecq enters an almost unbearable intimacy with her subject, mourning Modersohn-Becker’s untimely death at the age of 31, longing to reach back through time and touch her which, of course, is impossible. I have no barriers to such intimacy as I hold her book with my panties around my ankles. It is a book that can handle my exposed ass.

Through it I enter into what Julia Kristeva has termed a “jubilatory anality.” When I was a girl I asked—why doesn’t anybody go to the bathroom in the movies? The answer was—it’s because you were born in the 1950s—just wait—the sitting on the toilet shot will become a cliché—the woman with her long twiggy legs pressed together, tiny ass ballooning against the porcelain seat—the question you should be asking is why don’t women in the movies spread their legs when peeing or taking a shit, splayed crotch wafting disregard and funk.

At a small dinner party, I mention my angle would be that I read the entire book in the bathroom. Laughter ricochets throughout the room of artists and theorists. “Do you think that’s bad taste?” I ask. Pam says, “Yes, and that’s precisely why you should write it.” Bathroom stories ensue. Geoff has a friend who got a job in tech, and his friend was grossed out when he saw a coworker taking his laptop into the toilet stall—but then he realized it wasn’t just the one guy, they all did it. They also texted while standing at the urinal. I counter with how at San Francisco State women are always talking on the phones while on the toilet, but the worst was the student who would sit in the stall next to mine and shout at me questions about class. Anne scrunches up her face and says she can’t imagine talking to a student in the bathroom.

Observing the self, one taps into the larger culture in which it is embedded.

While I’ve read magazines and bits of books in the bathroom, this is the first book I read there in its entirety. I read it slowly, over many months. I looked forward to it punctuating my daily. Being Here Is Everything is written in a series of vignettes, which allows Darrieussecq to quickly shift perspective from close up to expansive, to move freely between narrative, analysis, and exposition. Within the vignette’s logic of accrual, time is fluid and circular, the past and present skittishly tapping against one another as in a recent Reddit joke of the day: The Past, Present and Future walk into a bar. Things get tense. In Being Here is Everything we get the history of portraiture, of female self-portraiture, the treatment of women artists then and now, the history of French art, of German art, the history of Germany.

We get Modersohn-Becker’s innovations in style and subject matter, how she painted the first ever female nude self-portrait: “The nude self-portrait of a woman, one on one with herself and the history of art.” No one produces in a vacuum, and Modersohn-Becker is presented as a figure in the crossroads of many layers of history. Each gesture she makes reverberates with larger forces. Beneath a vast German sky at the birth of the 20th century, the laughter of a young woman explodes into an array of vectors.

Modersohn-Becker is both never alone and always alone, a product of her times who sees beyond her times, altering the history of women and art. We get an overview of the final seven years of her life, her complicated friendships with Clara Westhoff and Rainer Marie Rilke, her courtship and difficult marriage to painter Otto Modersohn, the time she spent in Paris and its influence on her painting (funded at first by an endowment from her uncle, then by Otto’s robust art career), her frenzied productivity near the end (eighty paintings in 1906 alone). We get that in her lifetime, Modersohn-Becker only sold three paintings. The first sale was to Rilke, the second to artists Martha and Heinrich Vogeler, and the third to another friend, Frau Brockhaus—all of them used to subsidize Paula’s 1906 relocation to Paris when she flees the claustrophobia of domesticity. After seven months she and Otto get back together, Paula gives birth to a girl and eighteen days later dies of a pulmonary embolism, a common pregnancy complication back then.

The vignette is the perfect form for bathroom reading—and for our digitally-fractured, ADHD-raddled now. A book consumed in discreet paragraphs which are placed next to one another, bits which pile up almost imperceptibly to reveal a larger whole. The vignette disrupts the notion of life as a narrative arc. Death and life are held simultaneously. With her novelist’s eye for dramatic tension, Darrieussecq introduces Paula’s death on the second page. “Let us not forget the horror that accompanies the wonder.” Her death beats through the text like a drum, creating a visceral sense of mortality, and rendering Modersohn-Becker’s aliveness so bright I found myself rushing the book to my desk five feet away to scribble in the margins. Darrieussecq: “And then a self-portrait with irises. It is a tipping point, a perfect moment. Pure simplicity: this is me, these are irises. See: this is what I am, in colors and in two dimensions, mysterious and composed.” As I underline this passage, I wonder, Is this what Hedi loves?

Throughout, Darrieussecq asserts that Modersohn-Becker painted what she saw—local women, children, intimates, nature, herself. Regarding Modersohn-Becker’s pregnant nude self-portrait—the first pregnant nude self-portrait in art history: “She paints what she sees in front of her: that being-there, that presence in the world, which happens to be pregnant.” I think of the meaty tranquility of all those nursing mothers the Modersohn-Becker painted, and it’s obvious to me that had she lived, Modersohn-Becker would have painted the first nursing self-portrait, and this feels like a great loss to the history of art in the western world. Sitting on my porcelain throne I wonder—somebody must have painted the first nursing self-portrait, but who? To reiterate the purity of Modersohn-Becker’s vision, Darrieussecq quotes from Rilke’s “Requiem for a Friend,” which he wrote a year after her death: “And at last you saw yourself as a fruit, you stepped out of your clothes and brought your naked body before the mirror, and you let yourself inside, down to your gaze, which remained strong, and didn’t say: This is me, instead: This is.”

In one particularly touching passage, Darrieussecq visits the Northern German countryside where Modersohn-Becker lived, and tries to see the landscape through the artist’s eyes. “The birch trees, their black-and-white trunks tilting against the bright blue canal, the sky plunging into the water like a knife.” The landscape seems unchanged until Darrieussecq reminds herself that separating her viewing and Modersohn-Becker’s are two world wars and the Final Solution.“ Paula was born and died in an innocent Germany.” Darrieussecq concludes, “The forests are not the same as they were.” Elsewhere Darrieussecq writes: “Paula is a bubble between two centuries. She paints quickly, in a flash.” The Nazis seized seventy of her paintings from museums, some of which they hung in the 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. Many did not survive.

Again and again the book returns me to my body.

Darrieussecq deftly includes herself in Modersohn-Becker’s narrative—how she came to learn of the artist, her encounters with the paintings in person, how Modersohn-Becker’s portrayal of a woman nursing is true to her own experience of nursing a child. But she never competes with Modersohn-Becker or overwhelms her, never tries to make the book her story. At the same time, she makes it clear that this is not an official version of Modersohn-Becker’s life and art, but one woman’s resonance with it. “And, through all these gaps, I in turn am writing this story, which is not Paula M. Becker’s life as she lived it, but my sense of it a century later. A trace.” As I reach back and flush I appreciate Darrieussecq’s integrity.

Writing about the self is not necessarily narcissistic—though, particularly with the rise of online “journalism,” I could point to dozens of examples that are eye-rollingly so, where the grandeur of the self threatens to eclipse whatever it encounters. When one observes the self, if one stays true to what one sees there, the self becomes a portal for the rest of the world to rush into, a wavering point from which history past and present streams. Observing the self, one taps into the larger culture in which it is embedded. When Tongo Eisen-Martin visited my Writers on Writing class at San Francisco State, he spoke repeatedly about staying true to the moment in both writing and reciting poetry. He advised my students to follow the energy and to keep the ego out of it. He said that when you say to yourself, “This is working really well, I’m on to something here,” it takes you outside the process, and your work fails. This rigor towards a vision that empties oneself is essential in self-portraiture. This emptying is the key to Modersohn-Becker’s genius.

When I pick up Being Here Is Everything in all my humiliating materiality, I am there. Again and again the book returns me to my body. Sometimes there’s cramping, sometimes the sweetness of ease. As I write at my desk, behind me is litter and soggy tissue from deluxe rolls purchased at Trader Joe’s, urine flushed or not, the sudden stench of cat poo. Septic is Cockney slang for an American. I wonder if working on their laptops on the toilet brings the techies into their bodies—or if they’re so far gone in abstraction they could be anywhere. I hope one of them watches porn, soundtrack piped in through Bluetooth earbuds, fist pumping cock in slippery slaps—grunt grunt—here.

__________________________________

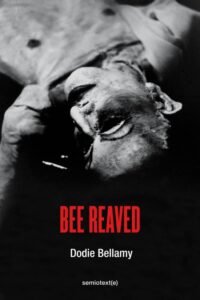

Excerpted from Bee Reaved by Dodie Bellamy, available via Semiotext(e).

Dodie Bellamy

Dodie Bellamy's work spans fiction, essays, poetry, memoir, sex writing, and blogging. Her books include Feminine Hijinx (Hanuman, 1990), The Letters of Mina Harker (Hard Press, 1998), and the buddhist (2011).