On Eric Garner, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Police Brutality as American Tradition

“¿DEFACEMENT?,” Inspired by the 1983 Police Murder of Michael Stewart

In the ancient medical treatise on traditional Chinese medicine the Huangdi Neijing, written by the Chinese emperor Huangdi about 2600 BCE, the lung organ is a bridge between heaven and earth, and the initial vessel to receive pure energy, or qi: “When the lung is cold, then both outside and inside [transmission] have come together. Subsequently, the [two cold] evils settle in the [lung]. This, then, causes lung cough.” And the breath negotiates the external and internal cycles of life. Grief therefore manifests as an imbalance in the lungs.

In 2017 Erica Garner named her newborn son after her slain father, Eric Garner. Only four months after giving birth to her son, Erica experienced an asthma attack that led to cardiac arrest, coma, and then death at the age of 27. After witnessing her father’s unjust death via news footage and citizen journalism, she seized upon the liberty torch and transformed his pleas for his life into protest chant—I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.

Eric Garner uttered this phrase 11 times when his asthma met the outsize stress of police ambush. As Paul Butler explains in Chokehold: Policing Black Men, Daniel Pantaleo, one of Garner’s arresting officers, used a chokehold even though the NYPD banned this excessive and lethal practice nearly 30 years ago.

In 1983 on the Left Coast, Adolph Lyons, a 24-year-old black man, sued the Los Angeles Police Department for placing him in a chokehold, in City of Los Angeles v. Lyons. Although the Supreme Court denied Lyons’s claim, the case created a legal precedent and discourse on chokehold practices in law enforcement. Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court justice, wrote in dissent, “It is undisputed that chokeholds pose a high and unpredictable risk of serious injury or death. Chokeholds are intended to bring a subject under control by causing pain and rendering him unconscious. . . . The result may be death caused by cardiac arrest or asphyxiation.”

In the same year of 1983, Michael Stewart, a 25-year-old black man in New York City, died of the hypothetical yet “undisputed” sequence noted by Justice Marshall—police chokehold, asphyxiation, cardiac arrest, coma, and then death. Thirty years and eleven mercy pleas later, Eric Garner suffered the same fate. In 2014 Broken Windows policing killed Eric Garner. Zoom back to the future in 1983, when transit officers beat Michael Stewart over his entire body of a mere 140 pounds.

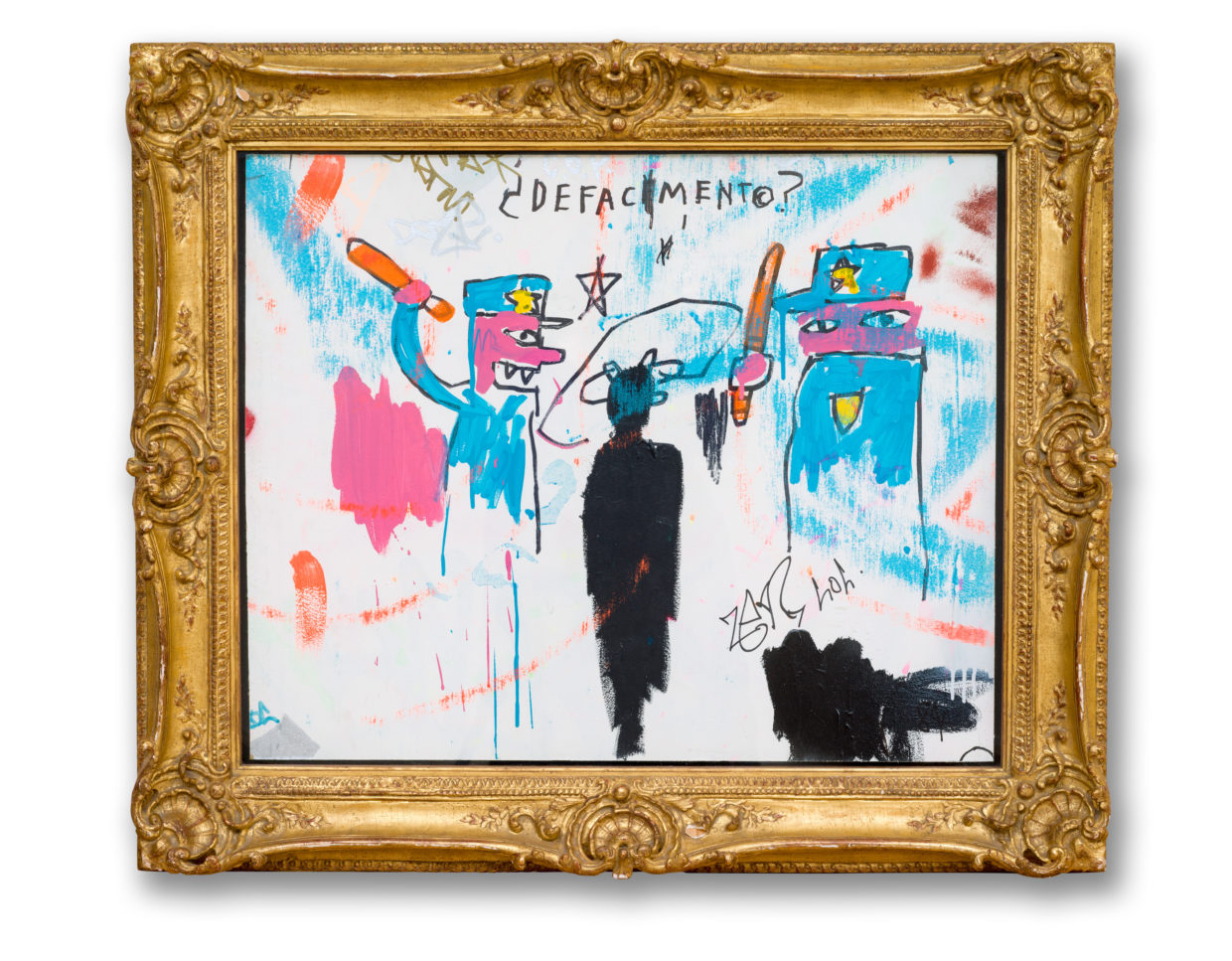

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), 1983 25 x 30 1/2 inches (63.5 x 77.5 cm), Acrylic and marker on wood, framed; collection of Nina Clemente, New York.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), 1983 25 x 30 1/2 inches (63.5 x 77.5 cm), Acrylic and marker on wood, framed; collection of Nina Clemente, New York.

According to Jennifer Clement’s Widow Basquiat, based on Suzanne Mallouk’s account of her relationship with Basquiat, “[Stewart’s] face is covered in small cuts and bits of glass are visible in his flesh.” The city’s chief medical examiner, Dr. Elliot M. Gross, first reported to the press that the cause of Stewart’s death was cardiac arrest, with no evidence of beating.

Forensic pathologists that worked on behalf of the Stewart family found the final cause of death to be strangulation by an illegal chokehold with a nightstick, and a massive brain hemorrhage. To bleach evidence of the blood veins in the eyeballs indicative of hemorrhage, Gross removed them and placed them in a formalin solution so they might become as blindingly white as the lies that construct and reproduce white supremacy.

Stewart belonged to the downtown scene, but his humanity would be claimed citywide. As graffiteros would say, Stewart’s spirit went ALL CITY. His death catalyzed a civic moral reckoning against the drumbeats of Reagan’s moralistic culture wars. Graffiti became the cipher for straw-man arguments used to justify police violence. In response to the tragedy, Keith Haring created a large mural titled Michael Stewart—USA for Africa (1985). Haring’s imagery connects the police strangulation of Stewart to the violence of South Africa’s apartheid regime. The anti-apartheid struggle had become a site of burgeoning Afro-diasporic internationalism and global protest through a disinvestment movement.

Unlike Basquiat’s ghostly figures, Haring’s extremely graphic depiction features Stewart’s naked black body with a neck stretched by the nightstick chokehold of two enormous peach-toned fists. Haring realized the scene as a large mural, nearly 10 feet in height by 12 feet wide, that reenacts the violation against Stewart on a spectacular scale.

On the wall of Haring’s studio in the Cable Building two years earlier, in 1983, Basquiat created his own tribute to Stewart, the diminutive Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart). The distinction between their responses reveals the underlying racial divide that existed among white and black participants in graffiti and art society. According to scholar Frances Negrón-Muntaner, “The Haring-Basquiat counterpoint enables an analysis of the role racialization plays in the making of commercially viable artists.”

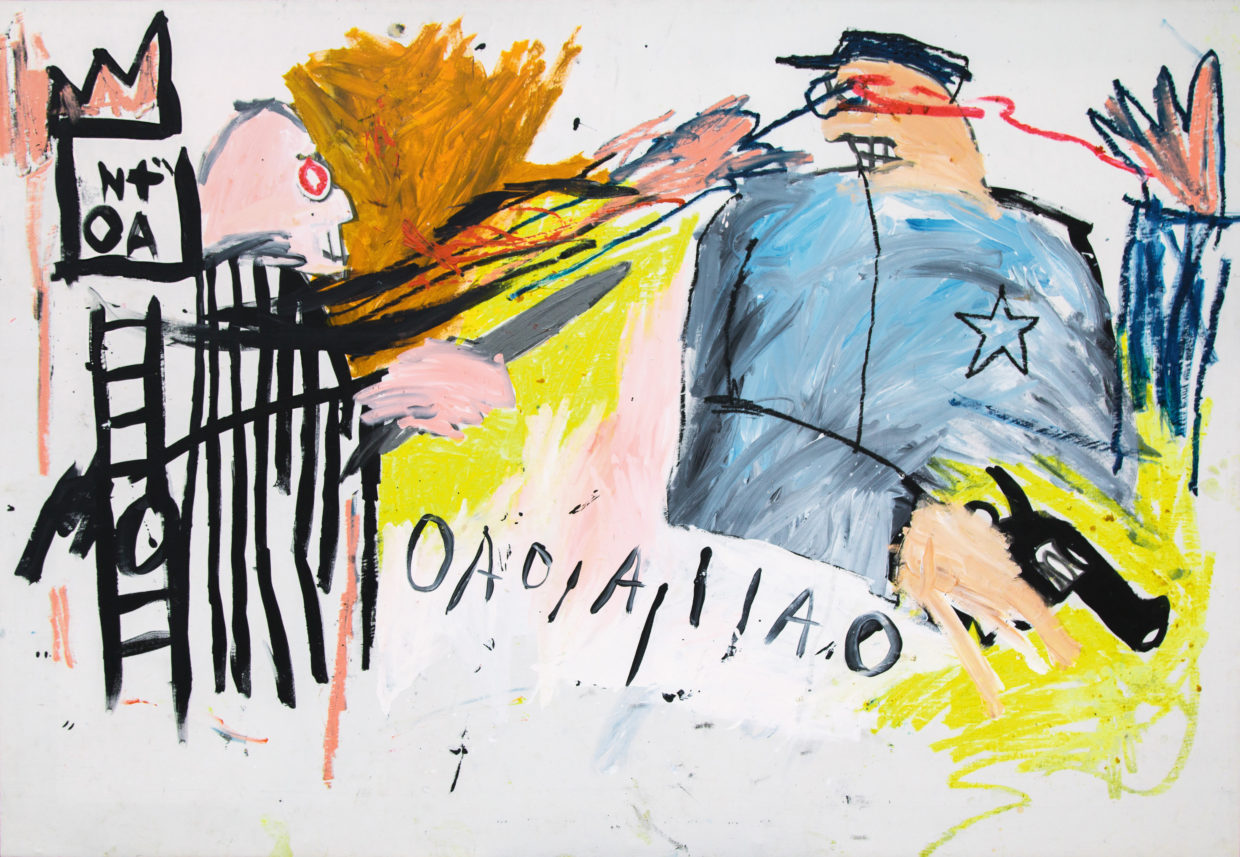

Jean-Michel Basquiat, La Hara, 1981, Acrylic and oilstick on wood panel, 182.9 x 121.9 cm, Arora Collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, La Hara, 1981, Acrylic and oilstick on wood panel, 182.9 x 121.9 cm, Arora Collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

With regard to physical safety and personal security when doing graffiti, Negrón-Muntaner continues, “Haring broke the law and risked being caught by drawing along the subway stops, yet once he was arrested the artist received lenient treatment.” Basquiat knew the risk for him was perilous, even fatal.

The word “¿DEFACEMENT?” hangs over the violent scene depicted in Basquiat’s painting, but with its legibility complicated: the central E has been marked over. The stain in the middle of the word bifurcates it; the word itself becomes broken. Defacement can evoke multiple meanings. The primary connotation signifies vandalizing property with any foreign material applied to a surface, disrupting its original appearance. In the seminal graffiti documentary Style Wars, also from 1983, graffiti writer IZ describes the antagonism between writers and the train, stating, “This is the transit system. They don’t like it to be defaced.”

In a High Times feature by Glenn O’Brien titled “Graffiti ’80,” graffiti legend and subculture hero Lee Quiñonez reacted to the term:

“I hate that word defacing; it’s a sinful word to me,” says Lee. “People say, ‘It’s not yours, Lee. It’s not yours.’ I say, ‘I don’t care!’ I just want to make it nice. Wake you up in the morning when you’re seeing the train. . . . People see my pictures, (he says) and say, ‘Wow, it’s really beautiful, but you’re defacing and destroying property.’ I say, ‘Then what the fuck are you saying it’s beautiful for?’”

Burning an entire car earned the respect of other graffiti writers throughout the city. The train was the most coveted surface because of its mobility and size and the risk associated with producing on it. Using a similar definition of defacement, Basquiat once described his collaborative style with Warhol: “Andy would start most of the paintings. He would start one and put something very recognizable on it, or a product and I would sort of deface it.”

An alternative reading of the term defacement could refer to Michael Stewart’s figurative decapitation by strangulation, the disconnection between his face and body, or a reference to the bleaching of Stewart’s eyes, removed from his body in the morgue as part of the city authority’s attempt to “save face” with a massive cover-up.

Basquiat applies Spanish punctuation, framing the word with the double question mark, posing defacement as a question or an exclamatory statement, a statement of outraged disbelief. Does writing your name on the subway platform justify physical abuse and death? Creating spectacle as a disciplinary gaze is a key dialectical strategy in maintaining the performance of race.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Sheriff), 1981, Acrylic and oilstick on canvas, 130.8 x 188 cm, Carl Hirschmann Collection. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Sheriff), 1981, Acrylic and oilstick on canvas, 130.8 x 188 cm, Carl Hirschmann Collection. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Historian Robin Kelley explains how lynching reflects the “history and character of police violence in the America of the 21st century precisely because it reveals the sexual and gendered dimensions of maintaining the color line and disciplining black bodies.” Kelley notes, “Even though only about one fourth of the lynchings from 1880 to 1930 were prompted by accusations of rape, and though a significant number of lynch victims were political activists, labor organizers, or Black men and women deemed ‘insolent’ or ‘uppity’ toward Whites, the most sensationalized and highly publicized lynching involved a Black man accused of raping a White woman: hence the genital mutilation. . . . More than anything else, lynching was a means of protecting the purity of White womanhood from Black male rapists.”

While the press described the catalyst behind the brutality against Stewart as a display of antigraffiti policing, artist Lyle Ashton Harris discussed an alternative history to explain the backstory of his photograph titled Saint Michael Stewart (1994). Harris, a native of New York, had befriended Basquiat at the nightclub Area in 1985, where Basquiat was a regular; such downtown clubs and dive bars mapped fertile ground for creativity and community.

Musician and downtown hero Felice Rosser recalled how Stewart would frequent the Second Avenue dive bar where she worked after he finished his shift at the nearby Pyramid Club, a job that connoted a certain status in the downtown scene. On the fateful night of his attack, Stewart had been socializing at the Pyramid on a night off; his coworkers would become primary witnesses for the case, attesting to his sober state.

Describing the inspiration behind his photographic portrait, Harris shared one rumor that had been circulating: that the police victimized Stewart because he was found kissing a white woman outside the train station. Whether or not this has been confirmed as true, Harris’s version reflects the local community’s cognizance of how the NYPD helped enforce social divisions of race, class, and sexuality.

Stewart’s killing symbolized how the growing practice of racial profiling created a visual death warrant against the bodies of young black and brown males. In an interview from 2017, Harris explains further, “But I think Michael Stewart, in a way, spoke to . . . the mythological saint, or the possibility of transcendence. Or the possibility of the spirit that cannot be destroyed, and that was the ghost that somehow ran through all of us.”

This ghost appears in many of Basquiat’s pieces and engenders a particular violence against black lives that is at once structural, historical, ongoing, and futuristic. “Gothic violence remains a part of everyday black life,” notes literary scholar Sheri-Marie Harrison in her essay “New Black Gothic.” In countless other works, Basquiat isolates body parts portraying the depersonalization and commodification of blackness. However, in his tribute piece to Stewart, Basquiat does not focus on black anatomy. Instead, the subjects are otherworldly. The face of the central, monochromatic figure that represents Stewart is blotted out. Facial features are obscured.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Back of the Neck, 1983, Screenprint with hand-coloring on paper, 127.6 x 259.1 cm, Edition 1/24, Brooklyn Museum, Charles Stewart Smith Memorial Fund, © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Back of the Neck, 1983, Screenprint with hand-coloring on paper, 127.6 x 259.1 cm, Edition 1/24, Brooklyn Museum, Charles Stewart Smith Memorial Fund, © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Caribbean studies scholar Jana Evans Braziel describes how the “black sarcophagus figure evokes entombment, a catacomb, a ‘defaced’ or violently erased human life.” Like the children’s game where one must catch another’s shadow, the stain reflects disembodiment, a falling apart.

Many graffiti writers frequented Haring’s art studio and marked up the wall surrounding Basquiat’s piece. For example, graffiti legend Zephyr wrote his graffiti tag on the bottom-right corner of the painting, next to an unshapely dark spot. Basquiat’s portrait obscures any specific facial features or recognizable body parts except for the head and shoulders, creating a black abstraction mimicking the very lack of distinction at the heart of racial profiling.

Scholar and poet Elizabeth Alexander describes the conundrum of articulating race at the moment of unspeakable acts of violence in response to what pioneering scholar of black Marxism and racial capitalism Cedric Robinson called “the pavement lynching of Rodney King,” 26-years-old in 1991:

What do black people say to each other to describe their relationship to their racial group when that relationship is crucially forged by incidents of physical and psychic violence which boil down to the “fact” of abject blackness? Put another way, how does an incident like King’s beating consolidate group affiliations by making blackness an unavoidable, irreducible sign which, despite its abjection, leaves creative space for group self-definition and self-knowledge?

Although race is a social construct, racial profiling relies on visual identification, or what postcolonial philosopher Frantz Fanon calls “the facts of blackness.” Devoid of any specific features, Basquiat’s figure of Stewart becomes a black everyman.

_______________________________________

Published by the Guggenheim Museum for the exhibition Basquiat’s Defacement: The Untold Story, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, June 21-November 6, 2019. Texts by Chaédria LaBouvier, Nancy Spector, J. Faith Almiron, and Greg Tate are supplemented by commentary from artists and activists such as Luc Sante, Carlo McCormick, Jeffrey Deitch, Kenny Scharf, Fred Braithwaite, and Michelle Shocked, who were part of this episode in New York City’s history, which parallels today’s urgent conversations about racism.

J. Faith Almiron

Johanna F. Almiron is an award-winning performance artist and interdisciplinary cultural studies scholar whose research focuses on the role of art, visual culture and performance in relation to social transformation. Her work has been supported by various awards including most notably the pre-doctoral fellowship at the Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African American Studies the University of Rochester.