I had first read the prose of Eileen Myles in a book of stories, Chelsea Girls and in the tiny one story Hanuman volume, Bread and Water. Because both of these use Eileen’s youth and apprenticeship as a poet as its main material it seemed the perfect (years old) introduction to their novel Inferno. The stories in Chelsea Girls actually read to me as a loosely girded novel. There seem to be lapses of time in between the stories that didn’t ultimately interfere with a total and lasting vision when the book ended. I had often thought back on the stories and how easy it was to believe in the feelings and reactions as they arise in voice of the narrator. Inferno deals in the same arena but with finer tailoring. It’s a much longer gown. The voice knows the tricks it can land, practically anything because of its custom frame, a relentless sense of containment someone else might consider warped but is in fact (when up and running), inexhaustible. The signature warp would be the absolute and totally biased truth. All utterances are created equal in Myles’s voice, the asides are as important as any rise or fall in the action, often they move the book forward, using the same sudden turns their poetry takes, the inner and outer life are both rendered in equal measure. The breathing in and out of the poet. How the poet takes in the phenomenal world spits it back out and gets led around by it.

The book is broken into three parts. The first begins with their home life in Boston and dying to get away and early inklings of thinking in poetic form. When their class is assigned to write their own Inferno Eileen is the only one to think to write a poem. It’s easy of course for any poet reading this to transpose themselves into the narrative. And if a non poet is reading it its as close to an inside track as one can hope to get. It’s the life of the mind on display through short little affirmations or closures within the voice.

We all took our look from Art Carney. Walking around in our undershirts and vests and soft hats. I was one of them. But I’m female so there was an added bit of danger people always attacked me with. Like I would find myself alone and something bad would happen. Nothing did, of course, but, economically I was pretty naked. Once people saw how broke I was they decided I was for sale. (Myles 21).

Part one centers on Eileen meeting with a young woman named Rita who enters under the guise of wanting to know about poets. She eventually coaxes Eileen into meeting two older Italian men with her. Part one begins with the two women meeting at a bar and closes with the actual date with the two men. In between Eileen mixes up getting an apartment in New York, becoming curious about the poetic landscape and eventually meeting some poets. Memory is definitive in Myles’s hands, the perfect sleight of hand for any and all embellishment. This is a self proclaimed poet’s novel whose main character has the same first name as the author. Whether or not the reader is at all familiar with Chelsea Girls or Cool for You (Myles’s first novel) they are free to invent. It’s like stumbling onto a strip of color film that can’t help but define their era, a thread through your life that you thought only existed in the xeroxed rushes of poems or stories, but Inferno is willing to turn us on at such length.

The poet takes in the phenomenal world spits it back out and gets led around by it.The linking of the several narratives is contingent on our willingness to go anywhere with them through the strength of their continually talking back to us. We get to be near them for the duration of this reading experience. It’s similar to hearing Myles read in person. Regardless of if they are reading prose or poetry. There is very little veneer between them reading onstage and being introduced to them afterward. There are some writers that you go and hear read only to find that they seem to enjoy fielding questions and answers more than actually reading their work. I’m thinking of Fran Leibowitz, even Gary Snyder. Eileen goes them one better by increasing their technical skill, the book never rests entirely on their speaking voice. Eileen seems to recognize poetry as a broad element at play in the world and holding it up as they do the remains fall back to us as charm. They can finesse behavior we might consider shocking by placing us near their heart in the moment of anticipation or glory.

The poet’s life is just so much crenelated waste, nights and days whipping swiftly or laboriously past the cinematic window. We’re hunched and weaving over the keys of our green our grey or pink blue manual typewriter maybe a darker stone cold authoritative Selectric with its orgasmic expectant hum and us popping pills and laughing over what you or I just wrote, wondering if that line means insult or sex. Or both. Usually both. (Myles, 65).

The considerations of being a poet are given a lot of place in part one. Only time can reveal your place within poetry so often “real poets” stay in the complete present, but then all along you are unconsciously moving away from the picture and gaining a larger view. This makes the sort of camera like retelling of Inferno possible. A camera that also remembers how it felt within each instance of recording. Myles describes attending their first poetry readings in New York. What they often hear first are the poets limitations. The way you might appraise a musician by the end of their first song. Any veil between the life and the words being read that is not a component of the rhythm feels phony.

I understood community. Going to the place and standing around. Aiming for connection to bodies, language and the future. I could be an artist. I had the tools. It wasn’t politics. Not that I knew. It was nothing. It was boredom turned electric. Music from cars. It was watching. Watching the scene.

I was going to look into the St. Mark’s poetry scene for sure but now I was outside rambling. I was in school. (Myles 41)

The science of existence was completely out there for me to explore. Me, a 25 year old female. There’s no mystery why poetry is so elaborately practiced by the young. The material of poems is energy itself, not even language. Words come later. Eventually I stood, a big human, the day spinning all around me. I pushed the pies into the refrigerator where they sat for a month. I tugged on one when I was hungry. I pulled on some cut off jeans. (Myles 44)

Inferno begins with a quote by Walter Benjamin, “A distracted person, too, can form habits.” This prepares the reader in some way for how much of the narrative is taken up with the habits of the poet. Being outside yourself so seamlessly as when a great poet can read and walk you through a “things to do poem.” The life of Myles’s prose and poetry seem dependent on the containment of split second spasms of thought. These all take place within a bereft or totally decadent hell. Selling their old sentimentally worn poetry anthologies for beer, or explaining what they love about their pack of Gauloises.

Myles can finesse behavior we might consider shocking by placing us near their heart in the moment of anticipation or glory.I remember the covers of Myles’s first book of poetry, A Fresh Young Voice from the Plains. The back cover showed a poet’s dream of weapons set out on a desk. A pepsi, cigarettes and typewriter. (It’s been years since I have seen the book actually.) They are small charms and pleasures that keep the poets kingdom in tact even as the rent is yet to be paid. There is some excellent cutting between scenes in part one. From sitting around a massage parlor being prematurely chosen by a group of men to sneaking into opening night at The Met and back to a nervous training segment that closes out the massage parlor scene. These are not risky jumps they are like the thinnest veils piled up. No scene is left long enough for the reader to forget anything, it is a series of rooms kept warm for the wandering guest. Eileen is actually sort of herded into the Met by the rushing of the large crowd, and feels like they are on the same sort of rails while on the date with Rita and the Italians.

I would be a man if I wrote. And being a man would render these steps I’m taking toward a place called Tuesday’s- Tuesdays in my masculine hands would be literature. Each step was a coin. Ting, the door flew open. It was art. (Myles 80).

Part two or the purgatory of this book is titled Drops. It takes the form of a grant application to The Ferdinand Foundation. Eileen cordons off certain periods of their life as a writer under headings like Solo Performance and The Upper Meadow. They are breaking the early nineties into chapters essentially. Returning to some topics they have covered and dealing with others out of sequence the reader is given a lovely sense of refraction. It’s sort of a witty case file, a joke on how one goes about editing a book like this and bearing out the evidence of having survived as a working writer. They chart the periods of not knowing where the next network of support will spring from. The form of the grant application doesn’t get in the way as it isn’t overplayed.

Once in a while Eileen reminds you that they’re asking for support but most often when we are completely inside the various stories. Money and support regardless of its source are necessary forms of protection in Myles’s purgatory. Drops works well as a vortex whose events overlap, like a well wrought fountain going full blast in the exact middle of the book. They are cataloguing different strategies of escape, mainly killing time with money. One of the longer sections here deals with living in the unused country house of two well known artist friends. Being a pet poet to rich painters that can’t help but be described as paradise but even within that exhilaration awkwardness abounds with the grounds keepers. They can never quite grasp why Myles is living in the house.

I called Todd each time I was coming and then had to march over to apologetically pry the O’Malley’s VCR away from them.

Thanks Todd I grinned backing out the door with the warm con- sole. I’m sorry Eileen I keep forgetting that you like to watch movies when you’re here. No problem I grunted the cord bouncing by my side as I wound my way along the darkening path to the house.

Todd was keeping a museum. And I upset his idea. I used every pan in the kitchen cabinets and one by one I discovered they were not pans at all. The kettle dispensed years of soap when I hit the faucet to fill. He scrubbed it with Clorox or something really harsh. Everything looked clean but noting was meant to be used cause the real people were gone. They hadn’t lived there for ten years. (Myles, 164)

The form of grant application has a reflexive and condensed influence on Myles’s style. Almost more like a lecture, the interjections can contain whole other worlds, then become just as easily closed off with a stack of rubble, a joke in their voice. There are also a few of their own favorite poems from the 90’s on display.

Shhh

I don’t think

I can afford the time to not sit right down &

write a poem about the heavy lidded

white rose I hold in my hand

I think of snow

a winter night in Boston, drunken waitress

stumble on a bus that careens through

Somerville the end of the line

where I was born, an old man

shaking me. He could’ve been my dad.

You need a ride? Wait he said.

This flower is so heavy in my hand.

He drove me home in his old blue

Dodge, a thermos next to me,

cigarette packs on the dash

so quiet like Boston is quiet

Boston in the snow. It’s New York

plates are clattering on St. Marks

Place. Should I call you?

Can I go home now

& work with this undelivered

message in my fingertips

It’s summer

I love you

I’m surrounded by snow. (Myles 121)

Eileen Myles once said to me that they had a lot of “handles” in their poems. I took that to mean places to make strategic crash landings every now and again. The traction of the poem is rewound when they stop to take a breath. Like if Robert Creeley only hit his line breaks so hard a quarter of the time. In between the voice feels thrown down concurrent flights of stairs. You need to hit the words correctly when reading aloud. The prose of Inferno works a little differently. There is more time allowed here than in the flashing tumult of Myles’s poetry. You get all wrapped up in the narrative that Inferno offers and they are forced to place themselves within the memories, or to dredge up a few more details to hold us as a film does.

The closing of Drops deals with a reading trip to Hawaii and Eileen getting lost after starting off too late toward an active volcano. On their way back from the glorious view they succumb to sheer exhaustion in the dark and sleep the night at the edge of a cliff. I found this section to be the most traditionally Dante inspired, as I had always imagined Dante and Virgil as action figures with the screen changing behind them as they muscle onward. Eileen in peril is absolutely fascinating as in every previous instance of the book they seem to always have an instantaneous cerebral response. There is something so endearing in their surrender to sleep here. Myles’s Purgatory manages to hold the whole heart of the book in its hands. The funding of a poet who has survived under such conditions is really the least any foundation can do.

I turned to the horizon. I headed that way. I saw a small house and those telltale piles of stones they call helau. Those little piles are holy. The house was the beginning of the road; there was my dark green rental car and my water and I drove out of the park and I had to get some caffeine, lots of it because I was falling asleep at the wheel. Everything was good after that, all three planes and especially now giving this account to you. (Myles 179)

Heaven feels different than hell but the actual backdrop is somewhat similar. The final section of Inferno has less of the desperation and unknowing of the first. Eileen has met poets they can speak with about the process of writing and they begin to perform their work. They also begin meeting women they want to sleep with bad enough to speak up. They are being given so much more attention. The rhythms of their life begin to fit effortlessly in sync with the rhythms of other poets and a new constellation of community begins to move on its own. Community is heaven and the way in which it drives you. Eileen is still being lead around to a degree but within the marked path of poetry. It has become a practice they can begin to believe in. These are fragments that sit and glow next to each other. They give off enough light to make us feel that these must have been joined at some point. It’s important to play with that edge during a reading of your work.

The walk to Roses was a flood of details. Car coming towards me as I crossed Houston. Put a cigarette between my lips. My lungs, this very good burn going down. I rub it. Flooding my chest like a flower. Go into the bodega and pick up a couple beers. The possibility that I should keep living in this particular time in which I had been born.,.not bleeding into all the other times, hear this footstep, not that. Feel that possibility and let it leak. Bump into a friend. Even if he was talking and talking I can jump in and stop him. People were hear- ing me now. A little bit. I liked standing up in front of a room full of people giving the torrent of words I chose. But each poem was a tiny torrent. A hole. Each person was a monad. A jot. (Myles 221)

Heaven is sleeping with Rose and the particulars of that experience. In an incredible chapter titled My Revolution these details bleed into remembering a host of past lovers, portraits of their vaginas really, one after the next.

But she was in there for fucking. I mean that’s pretty good. There was a small woman who had a lacy looking pussy that she hated. There was like this frottage over her clit. Instead of a hood it had a large mantilla. She wasn’t the kind of woman that could laugh at her puss. It made her sick what she considered her irregularity, the wave of skin that dangled between her legs. I would have told her it was pretty if she had let me. It was unique. (Myles 234)

It almost has that light sweep of humor and remembrance that one associates with the work of Kenneth Koch. Eileen finds the perfect opening to let the list march right through the novel. They really do tackle the form of heaven, the ultimate release of the form of their novel. One section entitled Friday is a dialogue between women at a table and a meditation on fish. The last sentence is,

“Yeah I’m definitely feeling a bit weak. The light looks weird. Yup, this is definitely going in.”

They have earned our attention and faith to the degree that there is even space for Myles’s to share fugitive pieces of writing that make the closing of Inferno possible. An instance of poetry absolutely infecting the prose, pieces like Friday usually function more like catalogues of parts, essential maps that often go unpublished. In the poet’s novel it is their prerogative to throw that kind of thing in especially as they have held us so long within the narrative.

There is less scaling the gaps of their life as in Chelsea Girls. This is the time afforded them to tell the story straight through then cut it all like film.Inferno has none of the pitfalls one associates with poetic prose, being underdeveloped or writhing within the surface and never getting past that or never getting off the ground enough to take the reader into another life. Myles’s does well to recognize that the public is more interested in poets than in poetry. They have probably helped to reinvent that fact. I think of Myles’s within the tradition of Jack Kerouac or Amiri Baraka, such fine all around writers that the designation of the poet’s novel is not so much needed. In their hands a poet’s novel just becomes a form that presents itself in order to continue writing. The material springs from the same mine field.

There is less scaling the gaps of their life as in Chelsea Girls. This is the time afforded them to tell the story straight through then cut it all like film. The editing of this work must have been such a pleasure. It mixes past and further past but remains just episodic enough that it never loses you. It sometimes takes a lovely kind of break into pure portraiture sketching their friendships with Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley and (more surprisingly) the great poet and art critic Rene Ricard. His is among the most unapologetically queer voices ever committed to paper. A true architect of queer and drag damaged vernaculars. Myles’s does a similar thing always talking right to you or taking you aside. They move the way they want within the text. During the reading of this book I would walk the streets and catch myself staring into the landscapes. I could begin to hear how I might wrangle my voice into blocking the stage of my past. It’s like seeing your life through a lens, exhaling and beginning to record. Throwing the subway platform up there and putting us on so we can get to the bar where the heavy curtain cuts the room in two. We are still nestled within Eileen’s mind and all the while it’s popping off.

Heaven is also where people die. Myles remembers in 1990 the uncountable deaths in the circle of AIDS. They mention the great poet Tim Dlugos as one of the first to die, as well as a friend from Provincetown named Paul Johnson. They first hear of his death at the Whitney, watching a video by Nan Goldin. Provincetown is a queer heaven that Eileen now feels equipped to actually enjoy. They love women and begin to hear in their poetry the possibility of transformation.

It was the only way to produce the kind of glancing and wincing and exclaiming-to depict a world of so many surfaces, wider than a book, the world’s pouring would have to be a curve, the line would be running, cursive, infinity a fight. The words needed to splinter off in some way just to describe it, so that any one poem would be a surge and nothing more, an intrepid break in time. (Myles 245)

Inferno would be an excellent book to hand to one’s parent, after years of their sneering at your unabashed involvement with poetry. We have a hero on our hands who has survived the depths of someone else’s famous epic and is writing their best sentences yet. How do you turn such a machine off? How do you disappear from a party in which you have told a major piece of your life story? This book went by so quickly.

__________________________________

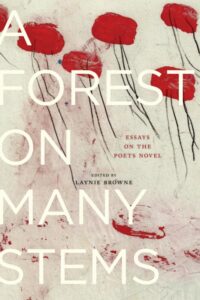

Excerpted from “The Doors of Perception in Eileen Myles’ Inferno“, from A Forest on Many Stems: Essays on the Poets Novel. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Nightboat Books. Copyright © 2021 by Cedar Sigo.