On Dr. Eduard Bloch, Hitler’s Family Physician (Who Happened to Be Jewish)

Meriel Schindler Traces Family Lore and the Unusual Correspondence Between Hitler and Bloch

I stand in the archway of the building where Dr. Eduard Bloch had his home and surgery: the Palais Weissenwolff at No. 12 Landstrasse. Embedded in the wall is a beautiful, wrought-iron disc bearing the words Haus Glocke, “House Bell,” running in raised letters round the outside. The bell-button itself, in the middle, is chipped and yellow like a nicotine-stained fingernail; a crack arches its way over the surface—evidence, perhaps, of the desperation with which the bell was rung repeatedly by the many people seeking Dr. Bloch’s services.

I know that the well-liked doctor took his calling very seriously. In all weathers, at all hours, he would put on his big black felt hat and drive his small horse-drawn carriage out to visit his patients at home.

“I never made the slightest distinction between the treatment of rich and poor,” he asserted in his later handwritten memoir. “I answered the call of every sick person, even in the coldest of nights, so that my constant readiness to help became almost proverbial.” No wonder that in its heyday, Eduard’s medical practice was one of the most successful in Linz.

Yet I know too, from reading his account that his success was evaporating even before the German Reich swallowed Austria in March 1938. The kindness, care and expertise that Eduard showered on his patients was no antidote to the poison coursing through the lifeblood of Austria. Older patients no longer dared visit him, as many of the youth of Linz were already enthusiastic followers of Hitler. Eduard later wrote of the city being a hotbed of antisemitic “illegals”—as the Nazis described themselves when they were banned—who called for a “return to the homeland.”

In his view, it was the intelligentsia who first advocated this Deutschnationale politics, and the working classes were then attracted to it as a response to what Eduard called the “previously unknown phenomenon of unemployment.” In such conditions, “poverty and hunger were the greatest enemies of morality.”

I turn my attention to the two large marble figures of Atlantes at the Palais Weissenwolff. The stonework is grubby, and the figures look careworn, slightly slumped, as they struggle to bear the weight of the first-floor balcony on the back of their heads and necks. Looking up at the balcony itself, I try to imagine what it would have been like for Eduard to witness Hitler’s triumphant return to the town where he grew up. The photographs and Eduard Bloch’s own account bring the scene vividly to life.

What Hitler said about him: “If all Jews were like him, there would be no Jewish Question.”

It is March 12, 1938. The crowds pack, seven or eight deep, along the pavement in front of the Palais, waiting excitedly for the arrival of the Führer. The early morning spring sunshine has helped tempt people out of their apartments and houses without heavy overcoats. Everywhere, there are now red, black and white flags emblazoned with the Hakenkreuz—the hooked cross of the swastika. Church bells are ringing, planes drone overhead, and loudspeakers relay the slow progress of Hitler’s convoy, traveling east from Braunau on the Austrian border—a border that no longer has any international relevance.

As Hitler’s large, open-top Mercedes finally noses its way along the Landstrasse, the crowds erupt, and there is an orgy of flag-waving and straight-armed salutes. For one thing, they are expressing their delight that Hitler has chosen Linz, his favorite Austrian city, as the first stop on his victory lap of Austria.

The city’s population has been ordered to turn on all the lights in the buildings facing the parade route and to close the windows. The Nazis are nervous about assassination attempts on the Führer. Despite this, some still stand on balconies, unable to contain their joy indoors. Eduard Bloch, though, is obedient. He stands inside by his first-floor window to watch Hitler’s motorcade roll by below him. It is a moment he will never forget:

I stood for a short time at my window full of anxious anticipation at the arrival. Standing up in his slow-moving car, Hitler saluted in all directions, including up at my window; I assumed that the salute was not meant for me but for one of my neighbors who was an enthusiastic Hitler-supporter. I was informed the next day that this “honor” was meant for me. Straight after his arrival at City Hall, the Führer asked after me.

Eduard’s daughter Trude later remembers that the following day a town councillor, Adolf Eigl, recounted Hitler’s very words to her: “Tell me, is my good old house doctor, Dr. Bloch still alive? Yes, if all Jews were like him, then there would be no antisemitism.” Trude can, she says, “swear to it.”

In truth, this is not a new revelation. Eduard has already heard messages about Hitler’s continued fondness for him, from his patients who were Nazi “illegals” and who made the short journey from Linz to visit Hitler at his Alpine retreat of Berchtesgaden. He knows, therefore, that Hitler thinks him an “exception,” an Edeljude—a noble Jew. He has already been told verbatim what Hitler said about him: “If all Jews were like him, there would be no Jewish Question.”

The doctor admits later to thinking that “Hitler could at least see something good in one member of my race.” Standing at his window, it is clear that Eduard has very mixed feelings and cannot help being a little proud at seeing the “frail boy” he treated so often, and whom he has not encountered for 30 years. Yet, he is not naïve. As Eduard peers at Hitler, over the heads of the crowd below him, he asks himself: What will he now do to the people I love?

*

For the rest of Linz’s Jewish population—those not considered edel—life changed almost immediately after the Anschluss. Eduard later described how all the Jews in Linz were immediately required to surrender their passports in order to prevent flight. Then, the Gestapo set about stripping them of their assets:

. . . they began the feared house searches, which normally took place at night or in the early morning hours. Naturally, nothing “incriminating” was found, but with virtuosic cleverness, a Gestapo officer knew how to slip “a communist leaflet” into a book on a shelf. Triumphantly, he would “discover” it and show it to the unhappy and appalled flat owner, as clear proof of membership of an organization which is hostile to the state. In this way, people who had nothing whatsoever to do with politics were labelled as dangerous enemies of the state; with that their fate was already sealed. Other members of the community were accused of tax evasion. In short, the Jews were arrested on the most unbelievable charges: after a few days all police cells were overfilled with Jewish inmates . . . National Socialist party people were posted outside shops and barred the entrance to shoppers; so soon the Jews were without the means of earning their living and the ruthless expropriations soon rendered them penniless.

Eight desperate members of the tiny Jewish community took their lives, terrified at what Hitler had in store for the Jews of Linz.

Even the Blochs were not immune to Gestapo attention, though for other and quite specific reasons. Sixteen days after the Anschluss, on March 28, 1938, some officers paid them a visit, while Eduard was out visiting a patient. “I am informed that you have some souvenirs of the Führer,” one officer explained to Lilli. “I should like to see them.”

He was referring to an article in a local newspaper, which mentioned that Bloch had two postcards and a landscape painting given to him by Hitler. That same article also described how Bloch had treated Klara Hitler “extremely conscientiously and compassionately despite her poverty.” Their interest piqued, the Gestapo now demanded the items be handed over.

Lilli located the two old postcards, which a grateful young Hitler had sent Eduard from Vienna before the First World War. As Eduard later described, one was a “penny postcard” view of Vienna inscribed with the words: “From Vienna, I send you my greetings. Yours always faithfully, Adolf Hitler.” The second was the one with Hitler’s own artwork inscribed: “Cheers Happy New Year.” A few years later, Eduard reflected that the Vienna period was “the one time in his life that Hitler was able to make successful use of his talent”—even though, in reality, Hitler had been barely getting by; sleeping in a working men’s hostel and scraping a living by painting such postcards.

Lilli told the Gestapo that they did not have the painting mentioned in the article. Later, Eduard conceded that he might have been given one by Hitler at some point, but had not retained it, because he was often given keepsakes. But Lilli did reluctantly hand over the two postcards, knowing—as did her husband—that in the current climate so much could depend on these little tokens of affection from an adolescent boy to his Jewish doctor. She could hardly resist; the officers would have torn apart the flat to search for them.

The Gestapo told Lilli they were “confiscating” the cards and gave her a receipt, a worn copy of which would survive, eventually to be lodged by my cousin John at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. It read: “Certificate for the safekeeping of two post cards (one of them painted by the hand of Adolf Hitler) confiscated in the house of Dr Eduard Bloch.”

_______________________________________

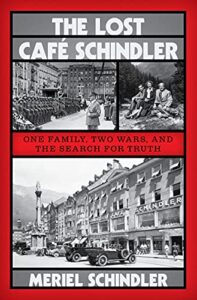

Excerpted from The Lost Café Schindler: One Family, Two Wars, and the Search for Truth. Copyright © 2021 by Meriel Schindler. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Meriel Schindler

Meriel Schindler is an employment lawyer, partner, and head of a team at the law firm Withers LLP, and is a trustee of the writing charity Arvon. She lives in London with her husband, Jeremy, and has three adult children.