On Doing Everything Possible to Avoid Becoming a Lawyer (and Failing)

Anna Dorn Tries to Stay Out of the Family Business

Whenever people asked about my dad while I was growing up, I’d quote Cher Horowitz in Clueless: “My dad’s a litigator. That’s the scariest type of lawyer.”

The “law” was passed down in my family like a hideous heirloom. My dad was a lawyer. My grandfather was a lawyer. Most of my uncles are lawyers. And it wasn’t just my family—most of the people I grew up with also had families full of lawyers. I was born and raised in what the Washington Examiner called “the lawyer capital of the world.” One in twelve Washington, DC, residents is a lawyer (the national average is 1 in 260). That meant most of my parents’ friends and my friends’ parents were lawyers. And most of these lawyers were men.

Despite my two X chromosomes, the idea that I would someday become a lawyer always felt inevitable. I spoke early. I was good at school. I don’t recall being interested in the law, but I was endeared to the idea of being right, of convincing someone else they were wrong, of intellectually embarrassing them.

All throughout my childhood, I watched my mother struggle to assert herself. I watched her get walked over and demeaned. I watched her shrink herself literally and figuratively. I watched how she’d abandon her own ambitions to do what was expected of her—to get married, raise a family, and accommodate that family’s every whim. This could not be my fate. I needed to be somebody. I needed agency. Becoming a lawyer felt like a vehicle to respect. I also enjoyed the television show The Practice, and like most children of the 90s, I got most of my ideas of what adulthood should look like from television.

My dad was a good lawyer. He wasn’t a good person, per se, but he was successful—a top international trade litigator. Though I often quoted Clueless to people who asked about my dad, my favorite movie was Liar Liar, a 1997 Jim Carrey film about a successful lawyer who frequently breaks promises to his son because he is focused on his work. The metaphor here is not subtle. When I was four going on five, I asked my mom whether she thought my dad would remember my birthday. She just shrugged.

Another reason I liked Liar Liar was because it counteracted the stereotype that lawyers are somehow more rule-abiding than everyone else. In my experience, both as a kid and now as an adult, lawyers are even less principled than cops. A lawyer’s job is literally to twist facts as far as they can possibly go in the client’s favor. So why does everyone then act shocked and appalled when lawyers do bad things?

My dad’s specialty was something called “antidumping,” which I always thought was an unfortunate name. My crude understanding (thanks to a brief internship with his firm in high school) is that he fought against foreign businesses that illegally dropped their prices in the United States to unfairly compete with American businesses. He made it sound like noble work, but in retrospect I’m dubious, particularly because he was defending American corporations, which, historically, have been anything but noble.

While writing the book Bad Lawyer, my dad texted me that he was going to write a rebuttal to my book called Good Lawyer.

I responded, based on what?

My experience as a lawyer, he said.

Do you think your work made a positive contribution to society?

Yes, he responded. I saved hundreds of factories and tens of thousands of jobs in getting remedies against unfairly traded imports from China and other countries. I also provided jobs and successful career paths to many young lawyers. I feel really good about my legal career.

My dad worked at King & Spalding, which one Glassdoor reviewer referred to as a “firm full of sexist, racist partners.” The Atlanta-based firm is known for having Coca-Cola as a client and for being the defendant in a historic 1984 sex discrimination case, Hishon v. King & Spalding. The Supreme Court held that Elizabeth Hishon had the right to bring suit against the firm for denying her partnership bid on the basis of gender. That same year, at the company picnic some men at King & Spalding decided that it would be fun to stage a wet T-shirt contest starring the firm’s female associates (I wish I was kidding). The men were less interested in breaking the company’s glass ceiling than in watching women slip and slide all over it.

When I was 27 and living in my childhood bedroom, my dad invited me to dinner one day after work. I walked from the courthouse where I was clerking to the sushi restaurant in Foggy Bottom where my dad and I always ate out, which we typically did without my mom. The restaurant was cold, sterile, and predictable—just like our relationship.

“Mom told me you, er… ” he stumbled.

I nervously sipped my Kirin Light, no idea where this was going. Normally, at these dinners, my dad talked about himself, and then I talked about myself and neither of us listened to what the other person was saying.

“She told me you are dating someone,” he continued.

I swallowed. “Yeah,” I said.

I was dating a woman for the first time, a fact I hadn’t told either of my parents. I was firmly resisting the societal expectation that gay people must come out. It’s an unfair burden to impose upon already marginalized people. Straight people aren’t forced to make any such announcements about their sex lives. I wasn’t hiding anything from my dad, actively, but I wasn’t going to start making announcements either. Announcements are tacky. Not my style. My parents ignored my dating life when I dated men and I expected them to ignore it when I dated women. This was the WASP way.

In my experience, both as a kid and now as an adult, lawyers are even less principled than cops.

“You know,” he said. I took another sip of my beer. I was terrified this was going to get cheesy. “King and Spalding was voted one of the best firms to work for gays and lesbians.”

I smiled, relieved. My dad’s response was so misguided that I had to appreciate it. He’d responded to the news that I was a lesbian with a statistic, with evidence, as though it was moral support. It was so classic. Classic attorney, classic my father.

My dad loved being a lawyer. He’ll say this even after—it seemed to me—King & Spalding pushed him out for being too old. His identity was so attached to being a lawyer that he had to hire a psychiatrist to prepare him for retirement, something he talked about for more than ten years before biting the bullet. To his credit, psychotherapy did make him easier to be around—he seemed, for the very first time, to actually listen when I spoke—but it couldn’t fix the underlying problem, that my dad ultimately cared more about being respected within the Big Law hierarchy than anything else.

Once while I was in law school, my dad, mom, granny, and I were having drinks in our sunroom. My dad looked absent as we chitchatted about various relatives; his mind was elsewhere. As soon as he finished his Manhattan, he excused himself. “I have to go write this reply brief.” He rubbed his hands together and grinned. I’d never seen him so excited.

He was ready to destroy his opponent.

And in that moment, I felt very related to him. The excitement of leaving a social situation to get to the keyboard. Mind spinning with arguments that were begging to be sculpted into clean and logical paragraphs. For me, the only time life feels promising is when I’m about to put an idea to paper. It’s the only time I feel confident and secure, like I know what’s going to happen—and I’m in control. My dad relished that feeling, too.

Growing up, people always said my dad and I were similar—a comparison that deeply offended me. I guess we’re both disciplined and self-absorbed, insecure and depressive. A law firm preys on these qualities and exploits them. Whereas I started psychoanalysis at 11, my dad channeled his pathos into making money and generating status.

He cherished his “top lawyer” accolades and bought gadgets he unsuccessfully used to woo his bratty children.

“Why did you want to be a lawyer?” I asked my dad when I was little.

“The richest person on my block was a lawyer,” he said.

Growing up, people always said my dad and I were similar—a comparison that deeply offended me.

Early on, I promised myself I would grow up to be nothing like him. I would fight my genetic conditioning and the frequent suggestions that I should become a successful lawyer like my father. I didn’t care about money or status, I told myself. In high school, I became a Marxist. I stopped eating meat and buying clothes. I meditated to become less argumentative; my mantra was “tranquil.” I wore hemp necklaces and spent most of my time in the darkroom, listening to Usher and getting a little high off photographic fixer, a mix of chemicals used in the final steps of processing film. Suddenly, flowers appeared magically on blank paper.

You know, typical white girl shit.

But fast-forward to when I was a junior in college, and it was time to start thinking about getting a job. I didn’t want a job. I wanted to stay in school. I wanted to keep writing papers and reading books that had nothing to do with the practical realities of actual life. I didn’t want to have to sell things, or myself, to the brainwashed masses. I was a Marxist!

But at the end of my junior year of college, I signed up for the Kaplan LSAT class with my friend Nate. We really didn’t want to get jobs and this way we could please our parents by mostly hanging out and watching Grey Gardens all summer.

But I surprised myself by enjoying the LSAT class, the clean logic puzzles that distracted my busy brain. I decided I could be a “good lawyer.” The kind that advocates for vulnerable populations and defends people who are wrongly accused of crimes. Or at least, that’s what I told myself. I didn’t have to be like my dad.

I would change the world!

__________________________________

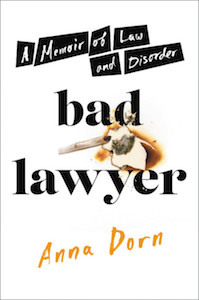

Adapted excerpt from Bad Lawyer: A Memoir of Law and Disorder. Used with the permission of the publisher, Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Anna Dorn.

Anna Dorn

Anna Dorn is the author of the novels Vagablonde and Exalted. She is an associate editor at Hobart Pulp. She was a Lambda Literary Fellow and her second novel Exalted is a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She lives in Los Angeles.