Naguib Mahfouz is the familiar face of Egyptian literature. If Egyptians haven’t read the Nobel laureate’s many novels, they’ve probably seen one of his films. What’s more, the master was always accessible to younger writers and fans at his weekly salons. Yet behind this warm availability was an intensely careful man who shredded his drafts, letters, and manuscripts.

Several years ago, prominent Egyptian critic Mohamed Shoair set himself the quest of finding the manuscript of Mahfouz’s most notorious novel, The Children of the Alley. The book was first serialized in Al Ahram newspaper in 1959 and met with fierce opposition from a range of politicians and religious figures. After complaints flooded in to President Gamal Abdel Nasser, this brilliant parable became Mahfouz’s only novel banned in Egypt. It was also the novel that inspired the later attempt on his life.

Shoair, part of a new generation of Egyptian critics, was determined to find the original. He approached Philip Stewart, the novel’s first English translator, who joked, “perhaps it’s in a bank vault in Beirut!”

Stewart told Shoair that, while translating the book from copies of the newspaper, he’d asked for the original. But Mahfouz didn’t have it. He’d given the manuscript to Al Ahram, he said, and it was never returned. Almost a decade later, the novel appeared in Beirut, and Stewart speculated that someone at Al Ahram must have sold off the manuscript. Yet the Lebanese publisher, Dar al-Adab, told Shoair they didn’t have it. Neither did the archivists at Al Ahram.

When Shoair first asked Mahfouz’s only living daughter about the manuscript’s possible whereabouts, she said the family didn’t have anything beyond what was already well-known. But as he continued to question her, she remembered one box of old papers her mother had kept. And so they set a date for Shoair to come look through the box.

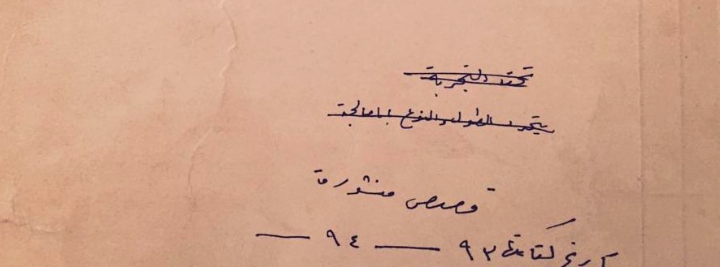

This magic box was a turning point in Shoair’s research. Although he didn’t find his smoking gun, the manuscript of Children of the Alley, he discovered many other drafts. Mahfouz wrote with a pencil, he said, on foolscap, and erased frequently. Then Shoair stumbled over something else: a fat file with a scrawled note on the front, suggesting the stories within were meant for publication in 1994.

Flipping through around 50 short texts, Shoair realized there were some among them he had never read before. For three long days, he searched for these stories among Mahfouz’s published works. Many of them, he found, had appeared in the magazine Nisf al-Dunia. But 18 of the short works had not been published anywhere, ever. “I don’t think Mahfouz ruled out publishing these works,” he said. “And their artistic value is strong.”

Shoair thinks Mahfouz lost track of the sequence of stories because of what happened on October 14, 1994. That’s when Mahfouz stepped into a car with a friend just as a young man approached. Mahfouz, thinking the young man was a fan, rolled down his window. Twenty-three-year-old appliance repairman-cum-terrorist Mohammed Nagui reached in and stabbed the great writer in the neck. Miraculously, Mahfouz survived, but a nerve in his neck was permanently severed. After a long recovery, Mahfouz couldn’t hold a pen for more than a minute or two. Still, he never stopped composing, and was forced to dictate his final short works.

Mahfouz died 12 years later, in 2006, at the age of 94.

Shoair says the stories in this new collection—titled The Whisper of Stars—recall the atmosphere of Mahfouz’s great 1977 novel The Harafish. The Arabic edition will be published on December 11: what would’ve been Mahfouz’s 107th birthday. Surprisingly, and to the chagrin of some Egyptians, they will be brought out by Dar al-Saqi in Beirut. Al-Saqi’s sister house in London is set to bring publish Roger Allen’s English translation next fall.

When Shoair first asked Mahfouz’s only living daughter about the manuscript’s possible whereabouts, she said the family didn’t have anything beyond what was already well-known.Roger Allen, a translator and retired professor, had a long relationship with Mahfouz. Indeed, Allen’s first published translation was Mahfouz’s short-story collection God’s World (1973), co-translated with Akef Abadir.

On a houseboat near Mahfouz’s home. “By this time,” Allen explains, “Mahfouz was substantially blind and not a little deaf, so the person to his left in the picture is what we called his ‘shouter’ who, every few minutes, would tell Mahfouz what we had been talking about. Needless to say, we would all wait for his responses, more often than not, very witty.”

In late October, Saqi Books’ Lynn Gaspard sent the texts to Allen for a reader’s report. After telling me this on the phone from his Philadelphia home, Allen gave a long laugh. He says he read through the stories quickly before he told Saqi, “you’ve got to be kidding—of course it’s worth doing!”

“I dropped everything and just started doing these,” Allen said. “I was so fascinated.”

Allen spoke with marked excitement, having just completed a first draft of the translation. Agent Yasmina Jraissati, who’s representing the work, calls The Whisper of Stars a collection of linked short stories, each with a twist, and each with “an ending that tells you so much about the characters.”

But Allen did not want to call them short stories.

“They are narratives that are short,” Allen said. “The thing that I find interesting…is that they are set in the same place, which uses the very significant hara, or quarter. The same setting, and the same set of characters, appear in almost all of them. You have the head of the quarter. The imam of the mosque. The local café. And above all, on the edge of this quarter, there is an old fort. Anybody who goes to that fort comes back somehow transformed. Like many of his later works, it brings in a very strong notion of the Sufi differentiation between the seen and the unseen, the known and the unknown.”

For Shoair, the detective work continues. In September, he published the first part of his trilogy on Mahfouz: The Children of the Alley: The Story of a Banned Novel. The second is in progress, with a working title The Manuscripts of Naguib Mahfouz.

Shoair added cryptically, over a Twitter direct message, that “the surprises don’t end here.” Soon, Shoair said, there will be an announcement about a discovery “perhaps more important than the stories.” When pressed on the nature of this announcement, Shoair responded with two large smileys.

![]()

The preceding is from the Freeman’s channel at Literary Hub, which features excerpts from the print editions of Freeman’s, along with supplementary writing from contributors past, present and future. The latest issue of Freeman’s, a special edition gathered around the theme of power, featuring work by Margaret Atwood, Elif Shafak, Eula Biss, Aleksandar Hemon and Aminatta Forna, among others, is available now.