On Deadly Policing and the 1979 Southall Protests

An Anti-Racist Demonstration and the Death of Blair Peach

On the evening of April 23, 1979, more than 2,800 police officers, 94 of them on horseback, confronted an anti-fascist protest outside Southall Town Hall, in order to protect a meeting taking place within that building for a National Front election candidate. By the end of the night, 700 protesters had been arrested, of whom 340 were charged, mostly with public order offenses. Sixty-four people were receiving treatment for injuries at the hands of police officers, including several with head wounds. And one anti-fascist demonstrator, a New Zealand-born schoolteacher, Blair Peach, was dead.

Perhaps the strangest thing about the fighting was the near invisibility of its seeming protagonists: the two dozen or so members of the National Front. One NF speaker, Joe Pearce, records in his memoir, “I was shuttled to Southall Town Hall, the location for the meeting, with a large police escort. As I gave my speech, I could hear a riot outside.” Clips survive of the NF’s supporters descending from their shuttle bus, waving their right hands briefly in the direction of the television crews, and then striding into the town hall, out of sight of the anti-fascist demonstrators.

The protection of the bus and the police was needed because in the days leading up to April 23, the people of Southall had demonstrated peacefully and in huge numbers against the National Front. There had been a public meeting against them, several hundred strong, and a march against them on the previous weekend before with 5,000 people taking part. That demonstration—in common with the crowd on March 23, 1979—was largely composed of first and second generation British Asian men and women, many but not all of them of Punjabi Sikh heritage. In the popular culture of the time, Sikhs were timid and deferential: the turbaned natives of It Ain’t Half Hot Mum. The real-life people of Southall were rather better equipped to deal with the Front’s racist threat.

The largest community organization in this part of West London, the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA), had been set up by supporters of the Communist Party of India. Its historian, John De Witt, estimates that by 1966 more than half of all Punjabi-born men in Southall were members of the IWA. Thirteen years later, the IWA remained a formidable presence, its members steeped in a tradition of political radicalism and a memory of colonialism and of anti-colonial struggle. They were part of a black working class and living in a decade of trade union struggles. Not only were the shops of central Southall closed on April 24 but so were a number of local factories: Ford’s truck plant at Langley, Sunblest bakery,Wall’s and Quaker Oats.

The events at Southall represented a collision between a radical black community and official opinion which may well have distrusted the Front but preferred nonetheless their right to speak over the rights of local residents to live without fear.

This part of West London had long been a target for the far right: a successful election campaign in 1964, when the British National Party’s John Bean stood for election in the constituency and came third with 9 percent of the vote, had been a key moment leading to the adoption of an electoral strategy across the British right, and the formation of the Front in 1967 as a coalition of Britain’s hostile and fissiparous far-right parties.

In 1976, a 16-year-old man, Gurdip Singh Chaggar, had been stabbed and killed in Southall by two white men, Jody Hill and Robert Hackman. Within days of Chaggar’s death, a Southall Youth Movement was launched at the Dominion Theatre.

The younger generation in Southall may have learned from their elders a tradition of protest, but they were trying to create yet more radical forms of struggle, and this inter-generational conflict could be seen on the April 23. The IWA was preparing for a National Front meeting which was due to take place in the evening. As the day wore on, and the scale of the police preparations became evident, the older generation urged anti-fascists to be patient. The younger generation were, however, unwilling to wait.

Stories circulated from house to house, warning that the police were planning to get around the sit-in by smuggling National Front members into the town hall early. Members of the Southall Youth Movement began to assemble outside there from around noon. Balraj Purewal of the Youth Movement led a march along South Road to the town centre. According to one participant interviewed by the BBC, “This is our future, right? Our leaders will do nothing… our leaders wanted a peaceful sit down but what can you do with a peaceful sit down here? We had to do something, the young people.”

“Someone somewhere was prepared to see people killed on a demo in Britain.”

Before 7:30pm, police tactics focused on controlling the streets immediately surrounding Southall Town Hall. Anti-fascists tried to guard the areas just beyond the police lines. Peter Baker was with them: “A roar went through the crowd. People turned and looked westwards down the street. I saw, to my amazement, a coach being driven fast straight into the back of the crowd. At a cautious estimate, I would put the speed of it at 15 mph, which is murderous when it is being driven into a crowd.”

Once the police had forced a way through for the National Front coach, their tactics changed and their objective became the dispersal of the remaining crowd from the vicinity of the Town Hall. Balwinder Rana was the chief steward on the anti-fascist side, “The police used horses. They drove vans into the crowd, and fast, to push us back. They used snatch squads. People rushed back with whatever they could pick up.”

During the evening of April 23, three main groups were the victims of aggressive policing. First, many people were arrested for being on the protest. A large number were teenagers. Several were simply abandoned by the police in the roads beyond West London and told to make their own way home. In the days that followed they suffered a particularly aggressive form of summary justice, with Ealing magistrates convicting at unprecedented rates. The following report, in the Guardian, was typical: “A 14-year-old Sikh boy appeared before a magistrate at Ealing juvenile court. He had been charged with ‘threatening behaviour’ and being in possession of ‘offensive weapons’ at 6.20 pm on 23 April 1979… [A] white doctor, a white solicitor and a white ambulance man… all testified that the boy, at the time, was being treated for a hand wound and had suffered a severe loss of blood… The boy was found guilty and fined £100.’”

Second, police officers broke into the Peoples Unite building which was being used as a medical centre to treat wounded anti-racists. Dozens of eye-witnesses complained that police officers aimed their batons at the heads of doctors, nurses and solicitors, as well as the protesters who had sheltered there. Clarence Baker, the manager of reggae band Misty and the Roots, was among those hit on the head by a police baton. He was so badly hurt that he spent five months in a coma.

Annie Nehmad, a doctor helping as a volunteer in the centre, recalls treating the wounded, including one man Narvinder Singh who had a three-inch wound in his right hand following a police attack. As the police came closer, she saw people running in the street outside and closed the windows and the door. The police demanded to be allowed in. Attempts were made to keep the door closed before the police succeeded in kicking the door in. She and a nurse were forced from the room. Nehmad herself, although identifying herself to the police as a doctor, was struck on the back of her head. So heavy were the blows that she stumbled and had to be rescued by other demonstrators. Looking back on the events, Nehmad insists that “On 23 April, not only were heavier than normal truncheons used but police throughout the demo used these heavy truncheons to hit people on the head. Someone somewhere must have said this was OK. Someone somewhere was prepared to see people killed on a demo in Britain.”

Also caught up in the events at Southall on April 23 was Blair Peach, a teacher at the Phoenix School in East London for children with special needs. Twice in 1978-9 he had been attacked by supporters of the Front as he cycled home from teaching at the Phoenix School and suffered black eyes and cuts to his hands.

On the fateful evening, Blair Peach travelled to Southall with a group of friends, Jo Lang, Amanda Leon, Martin Gerald and Françoise Ichard. He was part of the crowd that tried and failed to block the Front’s coach from entering the town hall. Shortly before 8pm Peach was on Beachcroft Avenue, where he was attacked by a member of the police’s Special Patrol Group and struck on the head—either by a police radio or by some unauthorized weapon.Another police officer Constable Scottow saw Peach stumbling after the blow. Scottow shouted at him to move on. After being taken in by a local family, the Atwals, Peach died in hospital, shortly after midnight.

Blair Peach was a socialist, an anti-racist, and an English teacher in his thirties who had fought all his adult life against an almost-disabling stutter.

The Special Patrol Group was a mobile unit within the Metropolitan Police Service, and was used against large demonstrations, such as the one at Southall. After Peach’s death, Ken Gill of the Trades Union Congress spoke at his funeral telling the 15,000 mourners that the SPG must be disbanded, “Every one of us must take up this call.”

As part of the police investigation into Peach’s killing, the lockers belonging to the half dozen SPG officers who had been in Peach’s vicinity when he was struck were raided. Some 26 unofficial weapons were found, including a leather-covered stick, two knives, a large truncheon, a crowbar, a metal cosh, a whip and a whip handle. The fatal wound had been large—larger, the pathologists advised than an ordinary truncheon—but had not broke Peach’s skin, as a wooden truncheon would have done. But the discovery of these weapons raised wider questions even than Peach’s death. How was it possible for officers to go on demonstrations with their own private weapons such as coshes or knives?

Peach’s death is remembered, among lawyers, for the manifest injustice of the inquest, and above all for the refusal of the Coroner John Burton to permit the jurors to read the report of the inquiry which had identified the probable culprit for Peach’s death, or to allow Peach’s family or their lawyers to know that one had been found. Three decades would pass before the report was finally disclosed.

Blair Peach was a socialist, an anti-racist, and an English teacher in his thirties who had fought all his adult life against an almost-disabling stutter. Singers Linton Kwesi Johnson, Mike Carver, Hazel O’Connor and Ralph McTell all released songs commemorating Peach’s death. He has also been remembered by other writers: Chris Searle, Edward Bond, Michael Rosen, Louis Johnson, Sean Hutton, Tony Dickens and Siegfried Moos all published poems in his memory.

Peach was a deeply private person, more comfortable in political rather than literary circles. No more than one or two of these writers can have known that in his youth Blair Peach had also been a poet. At the University of Wellington he had helped to edit a literary magazine Argot. Against the overwhelming horror of his untimely death perhaps a tiny satisfaction can be found in the way he has been remembered since: by the people of Southall as a man who fought alongside them, and by his fellow writers.

__________________________________

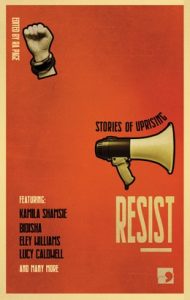

From Resist: Stories of Uprising edited by Ra Page, published by Comma Press and available in the US now.

David Renton

David Renton is a barrister and historian and the author of The New Authoritarians: Convergence on the Right.