On Creating the Cover For David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest

Steve Snider Remembers Trying to Visually Capture the Genius of DFW’s Magnum Opus

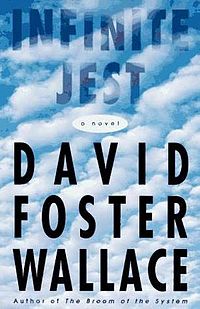

Sometimes, the cover of a book has its own story. In 1992, Michael Pietsch, a young editor at Little, Brown and Company acquired the rights to David Foster Wallace’s novel, Infinite Jest. After years of editing, what was to become Wallace’s magnum opus was published on February 1, 1996. As art director at the time, I was charged with the cover of the first edition. Infinite Jest is one of the most formidable and complex novels ever written, and it was immediately clear that designing the cover would be its own challenge.

Book covers can be literal, abstract, symbolic, atmospheric, and on and on. Often a single image can convey the mood or theme of the story, but what single image could convey the breadth of Infinite Jest? This, after all, is a sprawling postmodern tome with themes of sadness, loneliness, addiction, recovery, depression, mental health and suicide, plus sex, gambling, entertainment, and tennis! Heavy stuff, yes, but it is also a screwball comedy and often hilarious. So, how to package it?

Authors have ideas for the covers for their books all the time, and Wallace proposed several of his own, despite telling Michael Pietsch, “Don’t worry—I’ll not meddle much in graphics or stuff that’s not my business.” To be fair, he ultimately accepted the cover, which he did not like, but earlier he proposed using a photograph of Fritz Lang shouting through a bullhorn at hundreds of actors and crew on the set of the 1927 film, Metropolis. He thought the photo was “beyond cool,” and felt it could “even be good as a pastiche element in some very avant-g cover.” This image is mentioned in the book on page 951 but otherwise had no relevance at all, although, perhaps that was his point?

With Infinite Jest the concept of the cover is not to suggest any specific theme or symbol, but rather the scope and profundity of the book itself.

Wallace also liked a photograph of a man on a tennis court with a watering can watering arms that hold tennis rackets as they grow up through the court surface. Interesting, but creepy and not big enough in scope.

Another suggestion was a photograph of a field of antennas that had appeared in a United Colors of Benetton ad. That one had some merit. Michael Pietsch thought it the best of the suggestions since it worked as “a textural element, signaling communication, repetition, and proliferation.” But I felt it was still too specific. And then there was Wallace’s “dream cover,” a photograph of a 1982 installation by the American sculptor, Nancy Rubins. Titled Worlds Apart, the 40-foot-high sculpture was created out of used household electric appliances, concrete, rebar, and steel. It’s a striking piece, but too subtle and finely detailed for the cover of a book that was already so demanding.

Michael convinced Wallace that it was the jacket’s job to get the book into the buyer’s hand, and that we were aiming for something that looked grand and intriguing and approachable, something comic and serious, something that would offset the daunting thickness of the spine. At over 1,000 pages, and 2 3/8 inches thick, something more substantial yet accessible was required.

I felt the way to achieve that goal was not through specific imagery, but to announce the book’s importance with a Big Book look. The novel derives its name from the famous line spoken by Hamlet referring to the skull of the court jester, “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio: a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy…” and the word “infinite” was what I zoomed in on.

In their insightful investigation of the cover design process, The Look of the Book, esteemed designer, Peter Mendelsund and researcher David Alworth describe “The Big Book Look” as typically incorporating “very large type, the larger the better,” “a single color background”, and “small emblematic imagery.” In this case, the clear choice for the color background was blue, as it recurs throughout the novel.

In an early scene, when Hal, the main protagonist, is being taken to the hospital on a stretcher, he observes “the blue sky is glossy and fat with heat.” Elsewhere, “…the lip of the cool blue tub…” “…blue smoke…”, “…fat fingers of blue light from one sky,” ”out of the blue,” “from somewhere blue.” But rather than solid blue, I decided to go for a blue sky with clouds which I felt was a better way to suggest infinity, and also generic enough not to be off-putting.

Given the themes of mental illness and its treatments, those who follow meditation may note the allusion to the Blue Sky practice, where thoughts and emotions are seen as passing clouds against the backdrop of a constant, unchanging blue sky that represents the mind. For the literal minded, there is a precise description of the sky nearly halfway through the book. When Hal is waiting in the office of Charles Tavis, headmaster of the Enfield Tennis Academy, one of the story’s primary settings, Wallace describes the many things in the room that are blue: checks in the shag carpet, chairs, magazine covers, slices of blue sky in photographs hung on the walls, even the sills and crosspieces of the office’s two windows are described as in the blue family. “And also the overenhanced blue of the wallpaper’s sky, which the wallpaper scheme was fluffy cumuli arrayed patternlessly against an overenhancedly blue sky…”

Hal has just seen this same wallpaper in the dentist’s office. “Hal loathes the sky-and-cloud wallpaper because it makes him feel high-altitude and disoriented and sometimes plummeting.” Wallace’s choice of the words “high altitude” is an amusing coincidence to me because his main objection to the cover was that he felt it looked like an American Airlines in-flight safety guide. He thought the cloud system was almost identical.

The photo on the cover is a stock image, exactly what I had in mind. A bright blue sky and a pattern of clouds I could interact with the bold sans serif title type. Wallace wasn’t concerned with the size of the title, but he had reservations about the size of his name. He thought it absurd to make a 33-year-old 2-book writer’s name bigger than the title and asked that it be at least 25% smaller.

Considering the impact his book has made on the world, the size of his name, in retrospect, seems appropriate, as it did to me then. He also asked if there could be a couple of “little, tiny antennae (like from the Benetton ad) discreetly down in the left-hand corner, where they’d not intrude but could be seen if one looked.” I felt that a small element like that would distract from the overall simplicity of what is basically a symmetrical type design.

Instead, I added a bit of gimmickry by printing “a novel” in red inside an iridescent foil stamped oval. I hoped this unexpected touch would imply the lighter comic aspect while also subtly communicating the publisher’s endorsement of the book, i.e., their approval of additional production costs for foil stamping.

Book covers don’t happen by accident. Everything you see on the cover is a choice: the selection and sizes of typography, colors, imagery, graphics. The placement and relationships of all the elements are decisions made by the designer. We try to make art while recognizing that the book cover is a sales tool. For books with low or no advertising budget, the cover might be its only publicity. The designers’ responsibility to every book is to attract the right consumer. Will they buy the book?

That decision is made by other factors like the information in the flaps and/or back ad, but enticing the buyer to pick it up is the first step toward the sale. When a book under performs, the cover often takes some blame. That’s why we say facetiously that there’s no such thing as a bad cover on a bestseller. When the art department’s comps are ready for presentation, jacket meetings are held. The publisher and editor are present along with representatives from a number of the departments: sales, marketing, PR, production. Pleasing them all can be arduous. I’ve worked on books where upwards of 50 designs have been involved. But having what you believe to be a great design rejected should be seen as an opportunity. Creativity is a renewable resource and you can make something equally good and possibly better.

The final design for Infinite Jest was the only one I presented. Michael Pietsch approved it, the sales force immediately loved it, and everyone but the author were on the same page, so to speak.

While I’m not convinced that [Wallace] actually hated the cover, we do know for certain that he disliked it. And that’s disappointing for a designer.

It’s common knowledge that the first printing of the cover had to be reprinted due to a typographic error. The blurb on the back credited the writer, William T. Vollmann, with his name misspelled with one n instead of two. This was at the time when we had just started designing with computers in the art department and creating back cover copy in-house rather than having it done by outside typesetters. That spelling error was made by a young designer who prepared the mechanical, the art which includes instructions for the printer. Trivia fans may be interested to know that the young designer, Biz Stone, went on to achieve international fame, not for his typo, but as a co-founder and the patent holder of Twitter. I’ve never blamed Biz for the error. Little, Brown had some of the best proof readers in the industry, but somehow it got past them, as did many unintentional errors in the text.

The publication of Infinite Jest was marketed appropriately as a major literary event. Little, Brown sent out promotional postcards and special shrink-wrapped galleys signed by the author. By the time it was released there had already been early reviews and considerable buzz. It became an instant literary sensation. Sven Birkerts, in The Atlantic, called it “The next step in fiction…Edgy, accurate, and darkly witty…Think Beckett, think Pynchon, think Gaddis. Think.” The book went into multiple printings and eventually sold over 40,000 copies in its first year, so I was disappointed when the decision was made to repackage it for the paperback edition. I’ve always felt that Little, Brown should have stuck with the original to underscore its status as a classic. Many publishers have retained the original covers of classic books; Little, Brown and The Catcher in the Rye, for example. Since its publication, Infinite Jest has sold more than a million copies and had many covers through the years on domestic and foreign language editions.

Interestingly, a lot of them have echoed the blue sky/white clouds motif including the 30th anniversary edition designed by Gregg Kulick, who recently told Lit Hub, “The original cover’s sky has become such an iconic part of the book’s identity that it felt important to keep that as the core of the design.”

Readers and fans of the book have offered their own symbolic interpretations and thoughts on the blue sky/white clouds design. Many fans have no opinion at all. Others love it or intensely dislike it. Some even find it pretty. But any decent designer can make a pretty book cover. The stores are filled with covers using superimposed or integrated type on various, often random backgrounds. Those covers may imply genres, but better book covers are based on concepts that reflect the content of the book and signal it to the consumer. With Infinite Jest the concept of the cover is not to suggest any specific theme or symbol, but rather the scope and profundity of the book itself.

Years ago, online, Peter Mendelsund succinctly described his response to the cover as such: “…a perfectly blue sky…A sky that only an advertiser could have dreamed up—a sky that could have been subsidized…A sky that stands in for satisfaction, but a satisfaction that is almost sinister in its perfection…(and of course, HUGE type, because, well, that’s just what’s called for)…I think that was a very elegant solution. It tells you something very important, but leaves everything to the imagination.” If only Wallace could have seen it that way.

I’ve always truly regretted that he was so unhappy with the cover, but of course it’s understandable. His ideas suggest that he was hoping for something complex, and he got something minimal. It’s tough to see strangers dress your baby in clothes you deem unfit. When Michael Pietsch sent the approved comp to Wallace he explained that we had come up with a design that we felt accessible, inviting, and something that looked like a major serious work…a jacket that looks like a book you should have heard of even if by some chance you’ve missed the barrage of reviews and features and word of mouth. He concluded with, “Let me know what you think.”

Wallace’s 6-word response was “Got the jacket. Wow. Pretty sky.”

While I’m not convinced that he actually hated the cover, we do know for certain that he disliked it. And that’s disappointing for a designer. It’s so much more gratifying when an author is pleased with the packaging of their book. I have a fat folder full of letters, notes, and emails from happy authors. Such was not the case with David Foster Wallace. When he signed my copy of Infinite Jest, he wrote “For Steve Snyder—with many thanks.” I spell my name with an i, not a y. I sometimes wonder if that was an honest mistake, or Wallace flipping me the bird.

Steve Snider

Steve Snider is a graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he received the Senior Design Award. In his 50 year career Steve owned and operated his own design studio, served as Art Director of The Atlantic, Design Director of Arnold Worldwide, Art Director of Little, Brown and Company for 9 years, and Vice President, Creative Director of St. Martin’s Press for 18 years. He has also taught Graphic Design at the New England School of Art and Design. Steve’s numerous bestsellers and iconic book cover designs include Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, Vineland by Thomas Pynchon, Running With Scissors by Augustin Burroughs, and Barrel Fever by David Sedaris. He is the recipient of over one hundred design awards. He retired in 2015 to focus on fine art, making analogue collages. In May, 2025, Steve was an artist-in-residence at the London Collage Project. Instagram: @stevesnidercollage