On Creating Family in the Poetry Classroom

Ibi Zoboi and Liza Jessie Peterson in Conversation

Ibi Zoboi is a bestselling author and National Book Award finalist who has advocated for art programs for youth. Her most recent book, Punching the Air, is co-written with Yusef Salaam of the Exonerated Five. Liza Jessie Peterson is an award-winning playwright, actress, poet and advocate for incarcerated youth. She is the author of All Day: A Year of Love and Survival Teaching Incarcerated Teens at Riker’s Island. The two authors discussed their careers and the importance of art and writing programs for incarcerated youth.

*

Liza Jessie Peterson: What inspired you to write Punching the Air and where did the title come from? It’s so powerful and visceral.

Ibi Zoboi: Yusef and I met at Hunter College in 1999 where I was trying to get an interview from him as a member of the Central Park Five. We ran into each other again in 2017 and he was selling his self-published book of poetry. I was surprised that he had not yet written a book about his experiences. I write for teens, his tragedy happened to him as a teen. The rest, as they say, is history. We wanted this young character to be inspired by Yusef as a person—his worldview and his philosophy. He was really adamant about it not being trauma porn, and I agreed. It has to have some sort of light at the end of the tunnel. Although we didn’t want a story where the ending is tied neatly into a bow because that wasn’t his experience.

Yusef’s experience was more about him figuring out a way to cope, and he figured out a way to have hope for the next day. That line, “punching the air,” came up several times in the poems, and we were trying to find a line that says something. Yusef said that he remembered punching the air—like fighting something that isn’t there. He’s not a violent person, but of course, he wanted to throw a punch out of frustration. It’s like shadowboxing God. But it also can mean victory. Punching the air to show that you’ve defeated something. It has a double meaning.

You wrote All Day: A Year of Love and Survival Teaching Incarcerated Teens at Riker’s Island. It’s a long title.

LJP: Because that was my experience, and the kids’ experience. It was definitely an act of love, a relationship of love. They were surviving all kinds of trauma and violence. The courts, systemic racism. They were in survival mode. I was surviving the system of colonized education, the bureaucracy as an educator, and navigating the terrain of Rikers Island as an artist having to wake up at 4:00 in the morning to get to work at 7:30. I was kind of punching the air, too. But it was my love for my people and my love for Black and Brown children and wanting to see them grow, and their love for me as mama who is standing in the gap for their mothers. It’s part of our legacy as Black people in America to make family wherever we can find it because our families were torn from us. We created new families. That’s what was taking place in those classrooms.

IZ: There’s a teaching artist in Punching the Air that is inspired by you and your work. The love that you have for those boys really comes through.

When I met you, I didn’t know you as being a teacher on Rikers Island. I knew you as a performance poet. How did you get into writing and performing poetry?

LJP: Journal writing was my refuge, but I never considered myself to be a writer. I believed writing to be a something abstract and part of the land of intelligentsia and academia that I was not a part of. But I was studying to become an actor, so I was performing first. I studied with the National Shakespeare Conservatory, and the actor in me was always in performance mode, looking for a stage and a role. But I still never considered myself to be a writer until I was in a relationship that went sour, and I was writing my journal lamenting about my broken heart. I shared this journal entry with a fellow actor friend of mine, Sonja Sohn (from The Wire). She said, “Girl, that’s a poem, and you should read it at the Nuyorican.” So of course, the actor in me looking for a stage, and the audience took her up on the challenge, and I performed my journal entry. That was the start. My studying Shakespeare and my love of language sent me on a journey to studying the masters of poetry—The Last Poets, Sonia Sanchez, Lucille Clifton, and Amiri Baraka. I was gobbling them up like I used to gobble up Shakespeare.

IZ: Can you tell me about landing a role in the movie “Slam” (1998), which was a huge inspiration for Punching the Air? “Slam” stars the phenomenal spoken word poet Saul Williams, who plays a young man briefly incarcerated for a petty crime and develops a relationship with a writing teacher, played by your friend Sonja Sohn, while in prison. He’s a gifted poet and MC who feels trapped by his disenfranchised community in Washington, D.C. In the film, there is a slam event where you perform, and this scene serves as a climax in the movie where Williams’ character has a cathartic moment while performing his poetry. What was that experience like for you going from performing your journal entries at the Nuyorican Poet’s Cafe to being a fixture in the 90s spoken word movement in New York City and landing a role in a powerful movie like “Slam”?

LJP: That was a really magical and explosive time period. We were to poetry and spoken word what the young MCs were to hip-hop before it become mainstream. We were free-styling and battling each other with the fire that came from our bellies and we were doing it at the Nuyorican, Brooklyn Moon, Thoughtforms Underground. It was Mark Levin, the director of Slam, who come to a slam and Saul Williams blew him away. He had this idea for a movie, and he saw me, and I was friends with Sonja Sohn. It was a collective, we were a family, so we all were in the movie.

IZ: How did you go from being in a movie about an incarcerated young man to working with incarcerated youth?

LJP: Because of my reputation in the spoken word scene, I was hired to teach poetry and spoken word in schools throughout the city. I wasn’t gigging every day so I needed to pay for food, my phone bill… The poetry gigs weren’t paying. You might get enough to buy lunch the next day. It wasn’t sustainable. I was hired by a non-profit organization to go out to different schools to teach writing and poetry workshops. Teaching poetry to kids, it’s a win, win. We get to do what we love and get a steady check. My first teaching artist gig was on Rikers Island. That’s where I cut my teeth teaching poetry.

“Before, they all wanted to be anonymous, but when I would make it sound fly, they wanted to take credit for their work.”IZ: Yeah, these organizations get the funding to serve the most underserved populations and school districts. I was in the South Bronx and schools in East New York, Brownsville, and foster care agencies. The students were a challenge for me and I cut my teeth, too, because I had to cultivate a deep love for these kids in order to connect with them. And they had some of the most beautiful and passionate writing. Now tell me, what was one of your best experiences working with the young people on Rikers Island?

LJP: Well, the best was having a kid come to class and say, “I don’t like poetry.” And I’m like, okay. I’m still doing my thing, I’m teaching my class. And the next day, he comes to class and says, “Yo, miss. Look what I wrote last night.” Then, I would I would collect the poetry and say, “Now, I’m going to read the poetry.” And they would say, “No!” I said, “I’m not going to name any names. Let me just read it.” So the performer in me… I would put my extra stank on it. And then they would be like, “Yo, that was mine!” Before, they all wanted to be anonymous, but when I would make it sound fly, they wanted to take credit for their work. And then, they would all support each other and say, “Yo, who wrote that? That was fire!” So now, they’re bigging up their friends. Once they see it’s been approved by their classmates, they wanted to read it and take ownership of their work.

IZ: So at what point did you become an artivist—an artist and activist—as well as an award-winning playwright?

LJP: My first teaching artist gig was in 1997 or 1998. There was a correctional officer who said, you don’t know where you are, do you? So I said, yeah, I’m on Riker’s Island. He said, no, you’re on a modern day plantation. I had never heard this language before. This is before The New Jim Crow. This is before 13th. This was before when “mass incarceration” was even a word. We weren’t even using that term yet in 1998. He pointed to the boys walking down the hall and he pointed to them and said, “They’re the new crops. When you go home, put ’prison industrial complex’ into the computer and see what you find, and when I see you tomorrow, we’re going to have a conversation.” He literally boot-kicked me down a rabbit hole. When I got home and went on the computer, it was a vortex. I fell into an abyss. That’s what activated the artivist in me.

“This is what we want Punching the Air to do with young readers: Give them the language for what they are feeling and what they can’t articulate.”When I got back to the class, I had to share this information with them. I had to teach the word to those boys and what the truth is. My whole classroom’s dynamics totally shifted and became very political. And then, my boyfriend at the time, he got arrested and he was serving a federal sentence. My whole life was in prison—my professional life and my personal life. So the work was being fertilized. Out of that, I wrote a poem called “American Keloids,” and “The Peculiar Patriot” came out of that, my second solo show, and it was specifically about the prison industrial complex or mass incarceration, what we call it today.

IZ: In Punching the Air, the character Amal is very self-aware, what we used to describe as conscious back in the day. When I stared to write this with Yusef, I knew we shared the same worldview because we were both socially and politically aware as college students. When you worked with those boys, do you think most of them where hyper-aware of the hows and whys of their situation or do they still need some help understanding the larger context of institutional racism?

LJP: Both. It’s not either, or. Because I had a relationship with the boys I was performing for, there was already a revolutionary consciousness that they attributed to me. They were reading The Coldest Winter Ever and knew about Sista Souljah and they would call me Sista Liza. They would say, “Sista Liza talking that shit!” I knew what that meant. It meant that I was saying was resonating with them even if that was their first time hearing it. It woke up something in them. And that’s what the play did because I was giving language to what they were feeling and what they couldn’t articulate.

IZ: Exactly! This is what we want Punching the Air to do with young readers: Give them the language for what they are feeling and what they can’t articulate.

LJP: And they would say, “Yeah, that’s what I’m talking about!” It’s a like walking into a spider web. You can feel it on your face, but you can’t see it. I was giving language to that spider web.

IZ: That’s a great analogy. In Ghanaian culture, the keeper of stories is Anansi, the spider, and he weaves his story like a web. But sometimes that web can be a trap like you just described. Young people can get caught up in it, feeling it but not seeing it. With our stories and our work, we’re giving language to that web.

__________________________________

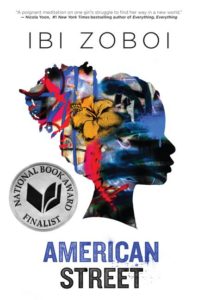

American Street by Ibi Zoboi is available via Balzer + Bray.