On Coretta Scott King’s Path to Civil Rights Activism

Matthew F. Delmont Explores the Progressive Politics of Coretta Scott King

By the end of the night, Coretta Scott King would become one of the nation’s most visible—and, to some, most dangerous—critics of America’s rapidly expanding war in Vietnam.

Standing before a crowd of eighteen thousand people inside New York’s Madison Square Garden on a warm June night in 1965, at the “Emergency Rally on Vietnam,” she had every reason to feel uneasy. She knew the FBI was watching. Civil rights activists like her were under constant surveillance, and whatever she said would end up in a government file. Outside, right‑wing demonstrators picketed the rally, accusing anyone who opposed the war of being a Communist or a Communist sympathizer.

And Coretta was the only woman invited to speak that night. She would take the stage alongside US Senator Wayne Morse, the political scientist Hans Morgenthau, the pediatrician and bestselling author Benjamin Spock, the civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Robert Lowell, who received a standing ovation for his recent refusal to visit the White House in protest of the war.

The ads for the rally billed her as “Mrs. Martin Luther King,” following the custom of the era. But if anyone in the crowd expected her to be demure, she quickly set them straight.

As she waited for the actor and activist Ossie Davis, her dear friend, to introduce her, Coretta gently thumbed through her notes, making sure the pages were in order. She had spent years thinking, organizing, and marching alongside her husband. Now she was eager to use her own voice to speak for peace.

The ads for the rally billed her as “Mrs. Martin Luther King,” following the custom of the era. But if anyone in the crowd expected her to be demure, she quickly set them straight.

“Have you often wondered,” she began, “why it is that the same President Johnson who speaks so eloquently for civil rights and who has been so moved by the struggle for the right to vote and the anguish of the poor can be so callous about the Vietnamese, and so apparently thoughtless on foreign policy?”

She let the question hang in the air.

In the three months leading up to the rally, the number of American troops in Vietnam had more than doubled—to fifty‑two thousand. On the day of the event, the State Department confirmed that President Johnson had authorized US ground forces to engage in combat if requested by the South Vietnamese Army.

For Coretta, the daily bombings were not distant policy—they were personal.

Many in the arena had voted for Johnson over the Republican Barry Goldwater just the year before. Now they were openly criticizing the president’s decision to commit the nation to a land war in Asia.

Coretta asked the crowd to consider the human cost of that policy.

Earlier in the evening, the father of Lt. Joe Thorne, a twenty-four‑year‑old from South Dakota, had taken the stage. His voice cracked as he read the telegram from the air force informing him that his son had been killed when his helicopter was shot down. He also shared one of Joe’s final letters, in which the young pilot confided that he believed the war was a “hopeless operation.” Thorne was one of nearly a thousand US service members to die in Vietnam in the first six months of 1965. It was painfully clear he would not be the last.

On the day of the rally, the front page of The New York Times detailed the US aerial bombardment campaign against North Vietnam, launched four months earlier. US Ambassador to South Vietnam Maxwell Taylor—former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and one of the architects of the war—stated he was “completely opposed” to ending the air strikes.

For Coretta, the daily bombings were not distant policy—they were personal.

“Where my husband and I have lived and where we have worked, poverty and bombing are not abstractions,” she told the crowd. “They are a part of the struggle of life from one day to another.”

She spoke not only as a peace activist, but as a mother. How could she explain to their seven‑year‑old son that the federal government was on the side of civil rights marchers, she asked, “only to have him watch on the television and see the very same troops we welcomed in Alabama, throwing bombs in Vietnam?”

Casting her eyes to the second tier of Madison Square Garden, ringed with American flags and patriotic bunting, Coretta closed with a theme she would return to again and again in the years ahead.

“Ultimately, there can be no peace without justice, and no justice without peace,” she said.

Calling peace and human rights the “two great moral issues of our time,” she urged the audience to educate their neighbors and bring enough people “into the streets” to make the president understand that Americans favored peace over war.

“Too many men have died in Vietnam while the country grows poorer, the people starve, and democracy is stifled,” she concluded. “We must begin negotiating now.”

As Coretta stepped away from the podium to thunderous applause, Bayard Rustin embraced her. A committed pacifist and conscientious objector during World War II, Rustin had organized the rally on behalf of the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE). Coretta had first met him when he spoke to her ninth‑grade class in Alabama about India’s independence movement, and later when he visited her college in Ohio. He introduced her to pacifism in her teens, and she watched as he helped bring Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance strategies into the heart of the civil rights movement. Rustin knew as well as anyone how much it meant for Coretta to step into the spotlight as an activist.

He picked up on one of the themes from her speech to close the rally.

“The time is so late, the danger so great,” he bellowed, “that I call upon all of the forces that believe in peace to take a lesson from the labor movement, and the women, and the civil rights movement, and stop meeting indoors, but go into these streets until we get peace!”

The crowd rose to its feet, clapping and shouting in approval.

With that rousing call to action, more than two thousand people followed Rustin, Coretta, and the other speakers out of the Garden for a midnight march to United Nations Plaza. The line of demonstrators stretched for eight blocks, lining Broadway as curious theatergoers looked on. Freedom songs and chants of “End the war in Vietnam” and “Bring the troops home” echoed off buildings, then slowly faded into the summer night.

The seeds of Coretta Scott King’s antiwar activism were planted in the fertile soil of Alabama. Her parents, Bernice McMurry and Obie Scott, were born and raised in Perry County, where their families had lived since the end of slavery. McMurry was the first Black woman in the area to drive a car and taught herself to cut hair so she could work alongside her husband in the barbershop they ran out of their home. Scott was the only Black man in town with a truck, which he used to move logs. The work put him in direct competition with local white men, who threatened him whenever he delivered lumber to the train station. He was routinely stopped on the road, cursed at, and threatened at gunpoint—but he never backed down. He began carrying a revolver, kept in plain sight in his truck, a warning to anyone who might think he was an easy target.

“If you look a white man straight in the eyes, he can’t harm you,” he told Coretta.

“Fortunately, I learned early how to live with fear for the people I loved. When fear rushed in, I learned how to hear my heart racing, but refused to allow my feelings to sway me.”

The Scotts were third‑generation landowners, but even landownership did not shield them from racism and violence. On Thanksgiving night in 1942, when Coretta was fifteen, white vigilantes burned their house to the ground. The family survived, but nearly everything they owned was destroyed—Coretta’s favorite dresses, books, photographs, and record albums all gone.

“The postcard from hell was my first taste of evil,” she remembered, “the kind that shows up at your door in such a way that you can never forget its smell, its taste, its sting.”

A few years later, Scott saved enough money to buy a sawmill. Two weeks after the purchase, when he refused to sell to a white logger, the mill was burned to the ground. The arsonists were never identified.

Throughout it all, Obie Scott never showed fear, even though Coretta and her siblings spent many nights worrying if he would make it home alive.

“He had the ability to deny people with ugly agendas the power to chase him from his mission,” she recalled. “Fortunately, I learned early how to live with fear for the people I loved. When fear rushed in, I learned how to hear my heart racing, but refused to allow my feelings to sway me.”

She was also not afraid to play rough. A self‑described tomboy, she climbed trees and wrestled with siblings, cousins, and friends.

“If another child angered me, I would fight, real hard,” she remembered. “I used to fight my sister and brother when they did anything that I didn’t like, so they used to call me mean.”

When Coretta graduated as valedictorian of her high school in 1945, she knew she wanted to leave the South. That fall, she enrolled at Antioch College, where her older sister, Edythe, had matriculated two years earlier. She majored in music and education—the first was her passion, the second practical.

At Antioch, she felt most at home among student activists. “Hearing young people give their firm convictions and conceptions concerning certain public issues was astonishing,” she wrote. She joined the campus NAACP, race relations committee, and a newly formed peace group. They organized rallies in support of students who were conscientious objectors.

“Pacifism felt right to me,” she said, “it accorded with what I had been taught as a Christian: to love thy neighbor as thyself.”

But even at a progressive institution like Antioch, Coretta encountered the quiet betrayal of liberal hypocrisy. When she was barred from completing a required student teaching rotation at the all‑white Yellow Springs public school, no professor, administrator, or classmate spoke up on her behalf. She fumed at the contradiction between the school’s values and its silence. The same “glib advocates of Democracy,” she wrote, tolerated racism in their own backyard.

“Do you then wonder why America as a leader among nations in the world today cannot command more respect among the common people who make up the majority of the citizens of the world?” she asked in her senior essay. From then on, she vowed to seek out people whose actions aligned with their ideals.

Coretta’s pacifism and support for civil rights led her to join the local chapter of the Progressive Party and attend its national convention in July 1948 as a student delegate. When she arrived in Philadelphia that summer, she was electrified by the atmosphere. More than twenty‑five thousand people crowded into Shibe Park, including throngs of young people who made the gathering feel more like a festival than a political convention. At twenty‑one, Coretta was one of thousands of students The Pittsburgh Courier described as “free souls who were unfettered by customs or accepted routines.”

But in the summer of 1948, she was alive to new political visions for America—and inspired by the possibility that art, activism, and global justice could be part of the same fight.

While the Progressive Party nominated Henry Wallace—President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s former vice president, who had been replaced on the 1944 ticket by Senator Harry Truman—Coretta was especially struck by the prominent role played by Black delegates and speakers. She heard fiery speeches from Edgar Brown, a founder of the National Negro Council, the Philadelphia teacher Goldie Watson, and John E. T. Camper, a Baltimore physician and World War I veteran.

“What do we want?” asked the playwright, composer, and activist Shirley Graham in her keynote. “That our children may dwell in peace. PEACE without battleships, atomic bombs and lynch ropes; PEACE without murderers masked as statesmen; PEACE without military conscriptions and mangled, torn bodies lingering on in veterans’ hospitals; PEACE in which to work and build.”

Peace, she emphasized, was not simply the absence of war—it was a question of national priorities. Why, she asked, was the United States backing the French war in Indochina? Why pour resources into the “hell of war,” when that same money could be used for health care, housing, food, and education?

As Graham concluded to a standing ovation, Coretta joined the crowd chanting, “Jim Crow must go.”

Building on Graham’s speech, the Iowa attorney and newspaper publisher Charles P. Howard delivered a sharp critique of US foreign policy. Howard, who had served as a second lieutenant with the Ninety‑Second Division, 366th Infantry in France during World War I, accused President Truman of using the Cold War to justify a sweeping peacetime expansion of America’s global military footprint. “We are told that warships in the Mediterranean are necessary; that bomber bases in Africa are necessary,” Howard said. “We are told that there is a dire threat to our security, and that we must arm to the teeth to protect ourselves from the Soviet Union.”

Coretta was struck by how Howard, who at one point waved a stalk of Iowa corn to rally the crowd, used homespun pragmatism to challenge the basic assumptions of national security.

But within the Progressive Party, the person who most influenced her was Paul Robeson. That summer, she had the chance to perform on the same program as the pioneering singer, actor, and activist at a meeting of the party’s Ohio chapter. After the concert, Robeson praised her singing and urged her to continue her training. Coretta was deeply moved—by his encouragement, but also by the figure he cut onstage, combining song with searing political commentary.

“After watching Robeson’s performance, I tucked it away in my memory,” she later wrote. “When I began my freedom concerts to raise funds for the movement, I patterned my concerts after his performances.”

For many years, Coretta avoided discussing her affiliation with the Progressive Party.

“The party was often accused of having links to communism,” she later explained, “and I did not want to besmirch my reputation.” But in the summer of 1948, she was alive to new political visions for America—and inspired by the possibility that art, activism, and global justice could be part of the same fight.

After she graduated from Antioch, Coretta’s dream of a singing career led her to Boston, where she enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music in 1951. She arrived in the city with just fifteen dollars in her pocket, living on peanut butter, graham crackers, and the occasional piece of fruit until she found work as a domestic helper in the home of an Antioch alum.

__________________________________

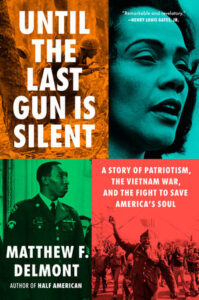

From Until the Last Gun is Silent by Matthew F. Delmont. Used with the permission of the publisher, Viking. Copyright © 2026 by Matthew F. Delmont.

Matthew F. Delmont

Matthew F. Delmont is the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History at Dartmouth College. A Guggenheim Fellow and expert on African American history and the history of civil rights, he is the author of four books: Black Quotidian, Why Busing Failed, Making Roots, and The Nicest Kids in Town. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and several academic journals, and on NPR. Originally from Minneapolis, Minnesota, Delmont earned his BA from Harvard University and his MA and PhD from Brown University.